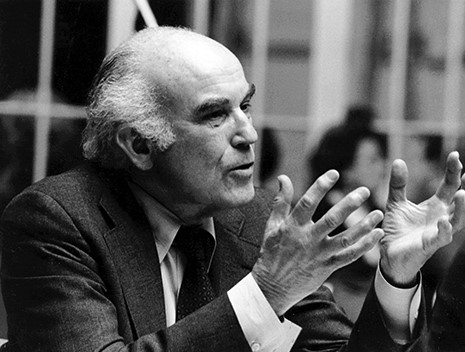

It is hard to imagine anyone today having a career like Robert Nisbet’s: professor at Berkeley, Arizona, and Columbia; dean and vice-chancellor at the University of California, Riverside; author of widely used sociology textbooks; and co-founder, along with his friend Russell Kirk and a few others, of postwar intellectual American conservatism.

Nisbet greatly admired Edmund Burke and Alexis de Tocqueville. Like them, he combined liberal sympathies with deep respect for tradition and the varied local communities in which it finds its natural home. The combination, together with his intellectual acumen, made him a favorite of the early neoconservatives, who were a group of leftist intellectuals shocked out of complacency by the ’60s and looking for ways to limit the excesses of what was called progress.

His great theme is the tendency of the modern state to absorb all social functions and reduce the people to an aggregate of unconnected individuals. Nisbet argues that the state justifies this as a process that supposedly liberates individuals from parochial oppression. But Nisbet saw the state as depriving individuals of a connection to a community, of a place to stand from which to exercise their freedom—so that ultimately freedom becomes useless. The free and equal individual created by the modern state turns out to be its victim.

In opposition to the state, Nisbet places the institutions of civil society: family, church, local community, cultural groups, and voluntary associations in general. It is these institutions in which the meaningful self-chosen activity that constitutes freedom finds a home. Nisbet saw the expansion of the state as weakening these organs of civil society for generations. As civil institutions weaken, individuals will be left adrift in the wilderness of modern social life, and will have to appeal to the state to provide a replacement for the home they have lost.

That disastrous downward spiral is central to the evil conservatives hope to alleviate, and it has only worsened since Nisbet’s death in 1996. No one treats the problem of cultural decline more acutely than he did, and anyone who wants to understand our situation today needs to read him. He is very helpful, for example, in understanding the relationships between war, the growth of the state, and social breakdown.

Not surprisingly, from a paleoconservative perspective, Nisbet’s worldview was not complete, and it needs to be supplemented in various ways. He is best seen as a traditionalist libertarian: His central commitment was to individual freedom, with tradition and social authority not as ends in themselves, but necessary chiefly for the sake of freedom. In this view he exemplifies, at a high intellectual and scholarly level, a basic tendency in mainstream American conservatism.

Nisbet’s writings show the strengths and weaknesses of that sort of conservatism. Its great strength is appreciation of the nature of the modern state. The U.S. had the first national government created as an arrangement for promoting strictly practical goals, such as national defense and commercial prosperity. But man does not live by such things alone, either individually or socially. Giving supreme loyalty to such an institution unguided by higher principles, and allowing it free rein to mold our life as a society, leads to social degradation.

For that reason, American conservatives have emphasized limitations on government jurisdiction and power, expressed through federalism, localism, individual rights, private property, and the institutions of civil society. A hundred flowers would bloom, we hoped, in a free society with strong families, vigorous local and private institutions, and limited government.

But this approach has limitations. Libertarianism can’t be pushed too far in a complex society, because power and social authority can’t be separated to the degree such a philosophy demands. Political authority, which holds power over life and death, needs somehow to be connected to our deepest concerns. The authoritative social institutions like religion and the family that Nisbet rightly emphasized can’t maintain their position unless their authority has some bite—which at some point requires the support of the law.

But this approach has limitations. Libertarianism can’t be pushed too far in a complex society, because power and social authority can’t be separated to the degree such a philosophy demands. Political authority, which holds power over life and death, needs somehow to be connected to our deepest concerns. The authoritative social institutions like religion and the family that Nisbet rightly emphasized can’t maintain their position unless their authority has some bite—which at some point requires the support of the law.

Nisbet’s libertarian leanings didn’t allow him to give them that support. He lumped laws forbidding abortion and allowing school prayer together with efforts to bureaucratize social life, seeing them both as instances of state imperialism. But, if the state is to be connected to our fundamental concerns, it can’t be wrong for it to defend basic goods like human life. And if the state is to educate children—and today it seems utopian to deny it that function completely—its schools will necessarily present some view of what life is all about.

One reason for his strong dislike of actual social conservatism is that his concern for informal social ties and transcendent commitments is rather abstract and theoretical. Unlike Burke, he’s not defending an actual society that possesses such things and unlike Joseph de Maistre he’s not proposing something specific that has been proven to work and is thought to have enduring validity. He’s a 20th-century social theorist who’s oriented toward abstract process and function, and who mostly wants the prevailing ties, standards, and commitments to have arisen freely, to reflect circumstances, and to function to bind society together.

A further limitation of Nisbet’s writings, one shared with all respectable conservatives, is that he wasn’t willing to say much about anti-discrimination laws and the politics of so-called social justice. The negligence is understandable, but it’s impossible to discuss the current situation of the evolved autonomous social institutions that he rightly makes so much of without taking it on. The problem has been radicalized in our “woke” and feminist age, but for a serious thinker it was hard to miss even when he was writing.

Nor does Nisbet say much about economics, technology, or religion, apart from pointing to the importance of the latter in his preferred social order. The most basic lack in his writings, one that I suppose is connected to his libertarianism as well as his evident religious skepticism, is that he presents no conception of the human or public good. Intelligent discussion of politics is impossible if we don’t discuss the point of the activity and the nature of human life and its intrinsic goods. Where he should talk about such things he talks instead about freedom and creativity.

This lack makes it harder to use Nisbet to think about our overall situation in an orderly way. He speaks of the need for a new laissez-faire that would emphasize the autonomy of social groups such as family, church, and locality rather than individuals. It’s hard to see why he didn’t connect this with subsidiarity, an established concept that proposes carrying on social activities as locally as possible with support only when needed from higher-order communities. Possibly he was put off by its connection to Catholic social thought.

The concept of subsidiarity, together with the concepts of human nature and the common good, would have enabled Nisbet to think more clearly about reconciling the state with the relative autonomy of other social institutions, and in particular to understand why laws that support fundamental social institutions like religion and the family are essentially different from laws that replace those institutions by state bureaucracy.

But these are criticisms of an outstanding thinker. The power and clarity of Nisbet’s analysis advanced conservative discussion enormously, and made it easier for others to identify what more they think is needed. For that reason, if no other, Nisbet must be read.

Image Credit:

above: Robert Nisbet (photo courtesy Intercollegiate Studies Institute)

Leave a Reply