When Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn wrote his 1974 book Leftism: From de Sade and Marx to Hitler and Marcuse, he dedicated it to “the Noble Memory of Armand Tuffin, Marquis de la Rouërie.” Tuffin was a French aristocrat born in 1751, and one of the first Europeans to come to the aid of the American colonies—even before Marquis de Lafayette—and one of the last to leave. By 1781, after the Siege of Yorktown, Tuffin was promoted to Brigadier General and became a friend of George Washington. He fought for each “free and independent” state in America, for liberty, and for republican ideals. Tuffin, who died in 1793, was also the leader in France of the Breton Association, a counterrevolutionary group that fought against the increasingly radical French revolutionaries.

Kuehnelt-Leddihn (1909-1999) saw his project in the same vein as Tuffin’s. They were both European aristocrats who fought for liberty in the States, in their own respective ways. Tuffin fought in the American War of Independence and Kuehnelt-Leddihn devoted much of his life to educating an American audience about the danger that their democratic system could devolve into tyranny. Yet today hardly anyone knows the work of Kuehnelt-Leddihn. Though he was a monarchist he admired the American system; he wrote in defense of liberty and despised democracy and egalitarianism. Given that many Western societies are currently threatened by mob rule, centralization, and illiberality, there is no thinker who deserves renewed attention more than Kuehnelt-Leddihn.

Kuehnelt-Leddihn was born in Austria to a noble family living under the rule of Emperor Karl I of the Habsburg Empire. He grew up speaking French and only at the age of five did he begin to learn his native German. This would be the preamble to his linguistic endeavors, which would result in him becoming a genuine polyglot. He would become fluent in eight languages and literate in 11 others—all of which were necessary to his research.

He started his studies at the University of Vienna in canon law, civil law, and Eastern European history, but transferred to the University of Budapest at the age of 18, where he received a master’s degree in economics and a Ph.D. in political science. He went back to the University of Vienna to study theology, but subsequently held successive professorships in England and in the U.S. at Georgetown and Fordham universities, as well as Chestnut Hill College. Kuehnelt-Leddihn was also a busy journalist, beginning with The Spectator as its Vienna correspondent at the age of 16.

In George Nash’s magisterial work on the American intellectual right, The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945, Kuehnelt-Leddihn deservedly finds an honored place. Although some might consider him a marginal character in the movement explored by Nash, this is far from the case. Kuehnelt-Leddihn was not a thinker of secondary importance, but rather a quiet titan who was befriended by many of the major conservative thinkers of the 20th century: William F. Buckley Jr., Russell Kirk, Otto von Habsburg, Friedrich A. Hayek, M. E. Bradford, Ludwig von Mises, Wilhelm Röpke, Ernst Jünger, and even Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger. Kuehnelt-Leddihn was an original columnist for Buckley’s National Review, where his “From the Continent” column ran for 35 years. He was also one of the first authors ever published in Kirk’s magazine, Modern Age.

above: cover of Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn’s book The Menace of the Herd or Procrustes at Large (Ludwig von Mises Institute)

This aristocratic polymath wrote for dozens of scholarly journals and newspapers, and published many books in both German and English. Among his English books one finds such worthies as The Menace of the Herd or Procrustes at Large (1943), Liberty or Equality: The Challenge of Our Time (1952), The Timeless Christian (1969), the aforementioned Leftism, and his 1982 essay, The Principles of the Portland Declaration. Among the themes in these estimable works are the merits of monarchy, the defects of democracy, historical liberty, the problem of egalitarianism, and the causal relationship between democracy and national or international socialism in the 20th century.

above: cover of Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn’s book Liberty or Equality: The Challenge of Our Times (Ludwig von Mises Institute)

A student of Tocqueville, Kuehnelt-Leddhin called attention to the totalitarian potential of democracy. It was not the rule of the people that he criticized, but the rule of the mob. The tyranny of the majority and the coercion inherent in attempting to produce a fully equal (or absolute) majority opinion were always of concern to him. He considered the tyranny of the majority to be the driving force resulting in oppressive governments since the French Revolution. The democratically-justified mob rule in that upheaval served as a blueprint for the coming 20th century experiments in tyranny. Adolf Hitler came to power through democracy by polls, and Vladimir Lenin through democracy by pikes.

Not only were these two horrific tyrannies spawned by democracy, but they were also in some sense socialist. Kuehnelt-Leddihn observed that the difference between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia was Hitler’s preference for borders—which resulted in national versus international socialism. During World War II, the two powers were not enemies so much as competitors in creating their own version of democratic tyranny.

For Kuehnelt-Leddihn, events like the Ribbentrop-Molotov nonaggression pact between Hitler and Stalin showed a coming together of two not entirely dissimilar oppressive regimes. Mussolini, named after the Mexican revolutionary Benito Juárez, began as a socialist. In the 1920s the young Nazi Party also constructed elaborate plans for nationalizing industries and redistributing income, even if Hitler later abandoned this project for reasons of expediency. Lenin and Stalin were, of course, true socialists, extinguishing dissent from the collective and assaulting natural inequality of ownership.

Kuehnelt-Leddihn saw the principles of egalitarianism and illiberality most exemplified by democracy. This is a form of leveling that Kuehnelt-Leddhin thought was inherent in democracy. To achieve such a situation, he insisted, force is required. To equalize that which is naturally unequal requires violence. This coercion inherent in the work of advancing unnatural equality stands in contradiction to the liberal principles of limited government and freedom. Human variety (not the current bureaucratically enforced “diversity”) uniqueness, and free will cannot thrive under egalitarian ideologues.

Today’s political culture would call forth a response from Kuehnelt-Leddihn. Since 2020, the pseudo-socialist/soft-corporatist establishment in America and elsewhere in the West has coerced many businesses to close due to COVID (favoring big business through government action), passed multi-trillion-dollar stimulus bills, and ultimately printed multi-trillions of dollars through the Federal Reserve—thereby devaluing the average American’s wealth. The left, meanwhile, threatens increased mob rule over our governments by fighting voter ID laws, advocating for Puerto Rico and Washington D.C. statehood, and abolishing the Electoral College.

Some on the right have conservative goals, but fail to see egalitarianism, majoritarian tyranny, and centralization as our deeper problems. Among anti-global nationalists one sometimes encounters little respect for localism, subsidiarity, federalism, or the prerogatives of the States. These are all challenges that conservatives face today, and they explain why Kuehnelt-Leddihn’s ideas still matter.

Where do we as rightists go from here? His essay The Principles of the Portland Declaration, which focuses especially on egalitarianism and the coercive power of the central state, can serve as a rough blueprint of what the right’s intellectual agenda ought to be going forward. If there are two things to learn from Kuehnelt-Leddihn, it should be the following: Beware of the tyranny of the majority and defend liberty at all costs.

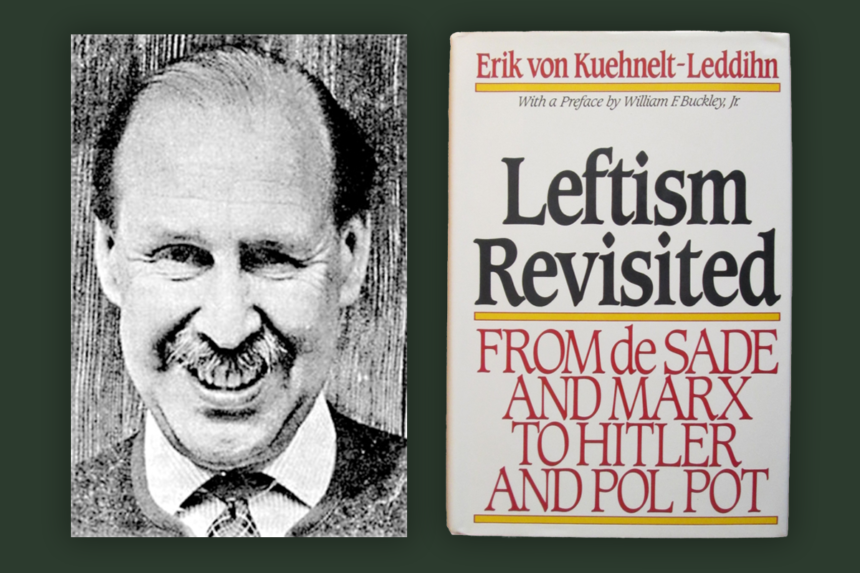

Image Credit:

left: Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn (public domain) right: cover of Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn’s book Leftism Revisited: From de Sade and Marx to Hitler and Pol Pot (Gateway Books)

Leave a Reply