Though John C. Calhoun was a distinguished American statesman and thinker, he is little appreciated in his own country.

Calhoun rose to prominence on the eve of the War of 1812 as a “war hawk” in the House of Representatives and was the Hercules who labored untiringly in the war effort. While still a congressman, he was the chief architect of the banking and tariff legislation of 1816. No less an authority than the banking historian Bray Hammond praised his “perspicacity” regarding the intricacies of banking and public finance. Calhoun also served with distinction as secretary of war, vice president of the United States, secretary of state, and a senator representing South Carolina. He was several times a candidate for president and enjoyed a national following.

Calhoun, together with Daniel Webster and Henry Clay, made up the “Great Triumvirate,” the leading political men of the antebellum period who shaped its policies and framed the issues of its great debates. Calhoun surpassed Clay and Webster as the statesman who most clearly perceived the dangers threatening the Union. Despite his achievements, however, few American politicians have been so vilified as Calhoun, especially in recent decades, yet he was one of our greatest champions of liberty, of the compact power of the states against federal consolidation. Though he is most often associated with the rise of secessionism, he was in fact a devoted servant of the Union, while nonetheless ever vigilant, both as a statesman and a political philosopher, against its potential for tyranny.

Calhoun was never without his critics. He is customarily charged with inordinate political ambition and hypersensitivity about his reputation. For some, Calhoun is a symbol of white supremacy and racial bigotry. Yale University, Calhoun’s alma mater, recently removed his name from Calhoun College, yet he is still recognized as one of Yale’s “Eight Worthies.” More subtle critics suggest that his sectional loyalties blinded him to any vision of national greatness. A recent and not unsympathetic biographer, Robert Elder, has written a book dubbing Calhoun an “American Heretic,” which is a curious appellation for a man whose ideas and political principles are grounded solidly in the American political tradition. And of course there is the legend of Calhoun the “cast-iron man,” the cold and aloof metaphysician who reputedly composed his love letters with the word “Whereas….” All of this is gross distortion and caricature.

Calhoun was a man of his time. He was no more ambitious or touchy than Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, James K. Polk or a host of other politicians in the antebellum era. As for his views on race, Calhoun’s belief that the United States was a white man’s country, and that Europeans were superior to Africans, was standard fare in antebellum America, North and South, no matter how offensive we may find such beliefs today. Political opponents called Calhoun’s devotion to the Union into question from time to time, but no serious scholar of Calhoun believes these charges were accurate.

above: illustration of the “Great Triumvirate,” statesmen Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, Henry Clay of Kentucky, and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina c. 1835 (J. L. G. Ferris, 1895/public domain)

As for the “cast iron man” image, abundant evidence testifies that Calhoun was a charming social companion. In society, he was singular among his peers in engaging women in discussions on the issues of the day. Many women commented that he treated them as equals and took a genuine interest in their views. Even Calhoun’s political opponents admitted that he treated everyone, from the pages in the Senate to presidents, with kindness and consideration.

At the same time, Calhoun was ardent in upholding what he believed to be right and strenuous in advocating his positions, which included defending slavery and the interests of Southern whites. To condemn him for this, as our contemporaries are apt to do, is to condemn his entire generation. It is rather rich that those who support abortion, embrace America’s forever wars abroad, and laud the oligarchs whose policies enrich the one percent at everyone else’s expense, thunder from their self-appointed judgment seats against the sins and sinners of the past.

The political theorist Francis Graham Wilson provides an antidote to the myopic and destructive presentism distorting our view of Calhoun. Wilson taught that a scholar must understand the people of the past as they understood themselves. With Calhoun, our understanding must begin with his Calvinist, Scots-Irish upbringing in South Carolina’s Upcountry. The Calvinism of these people differed from that of the divines of Essex and Cambridge who settled the “city on the hill.” Though severe in their moral judgments, Upcountry Carolinians such as his father, Patrick Calhoun, were suspicious of any schemes to erect utopias or to empower central governments, be they in Charleston, Columbia, or Washington. Liberty was the chief political value of these people. At most, government kept the peace, but no more than this.

The suspicion of consolidated government was not unique to the Scots-Irish. It had deep roots in the agricultural interest throughout the South. Calhoun was no different. He considered himself first and foremost a farmer and planter, not a lawyer, legislator, or political theorist. He wrote to many of his correspondents that he believed there is no better life than the farmer’s. He was happiest at Fort Hill, the family plantation, which for him was more real than the artifices of Washington, D.C.

By any measure, Calhoun was a successful farmer. He was a leader in the Pendleton Farmer Society and served a term as its president. He was not only a cultivator of the region’s leading cash crop, cotton, but successfully experimented with growing rice, importing Bermuda grass for erosion control, and cultivating silkworms—from which he extracted enough to make himself silk suits. He described farming as his favorite pursuit, and when at Fort Hill it so absorbed his attention that he paid little heed to politics. In Congress, he viewed his task as representing the agricultural interest. At the same time, his vision sought to accommodate what he considered the legitimate interests of industry and other sections.

Calhoun’s vision was national in scope. He did not fully share his father’s anti-federalist stance, and remained a staunch Union man, though he appreciated the anti-federalist fear of consolidated political power. Calhoun perceived that if the federal government could regulate or abolish slavery, the Union could not long endure. An old political nemesis, John Randolph of Roanoke, was Calhoun’s model of resistance. Calhoun once thought Randolph “too unyielding, too uncompromising, too impractical, but … had been taught his error, and took pleasure in acknowledging it.”

The North’s antebellum attack on slavery was, to Calhoun, part of a larger attack on the South’s economy, society, and equal standing in the Union. The abolitionists accused the South of inhumanity and cruelty. Stung by these charges, Calhoun defended slavery as practiced in the South as a “positive good” in its effects for both races and Southern society. He would not yield the point; he reasoned that to do so would have invited more invective and demonization of the South, which in turn would provoke Southerners to quit the Union. In this last point Calhoun proved prophetic.

Calhoun summed up his view of republican government in his Jefferson Day toast of 1830. In response to the words of Andrew Jackson’s toast: “Our federal Union; it must be preserved,” Calhoun parried with his own: “To the Union, next to our liberty, most dear. May we always remember that it can only be preserved by distributing equally the benefits and burdens of Union.”

His policies attempted to strike a delicate balancing act, to limit federal power but also to support the Union’s financial and industrial development. In addition to his mastery of public finance and banking, he was also keenly interested in railroads and the development of the Mississippi Valley for its potential as a great inland port. He hoped to tie the West and South economically, including the northern states along the Ohio River and Upper Mississippi Valley. If this seemed a type of economic discrimination against the Northeast, Calhoun was quick to point to the generous federal expenditures that paid for port and harbor development in the Northeast, as well as an extensive system of postal roads.

In foreign relations Calhoun was an advocate of peace and anti-imperialist. In the Oregon territory boundary dispute, he rejected President Polk’s bellicose rhetoric in favor of a policy of negotiation with Great Britain. Though it was viewed as advantageous to Southern interests, Calhoun opposed the war with Mexico. He was also a severe critic of what today is described as nation-building. To those who advocated the establishment of a friendly government in Mexico protected by the United States military, he warned that such a government “would inevitably be overthrown as soon as our forces are withdrawn,” luring the United States into a vicious imperial cycle of withdrawal and military engagement.

Calhoun’s commitment to republicanism and the equal sharing of benefits and burdens within the Union required magnanimity, restraint, and prudence. Without these virtues, he feared that popular rule would devolve into the tyranny of what John Randolph had called “King Numbers,” as political majorities oppressed political minorities for their benefit.

Calhoun rejected such predatory and divisive political practices. He supported the Tariff of 1816 as a gesture of goodwill toward a New England vilified by many for opposing the war of 1812. The region’s shipping industry had been decimated by its policy of neutrality, and many Yankee capitalists diverted investments into manufactures. To offer these infant industries some modest protection was in Calhoun’s view both prudent and magnanimous.

In the debates leading up to the Missouri Compromise, it was Calhoun who warned the South to beware of conspiratorial thinking and “disunion and all its horrors.” In 1828, the exorbitant rates in the Tariff of Abominations went well beyond modest protection and threatened the livelihoods of the agrarian interests, especially in the South. He viewed the tariff as both an attack on the people of his section and upon the principles which supported the Union.

He viewed the abolitionist assault on slavery in the same way. Calhoun argued that the Union was a compact of sovereign states, a point he forced Daniel Webster to concede during their 1833 Senate debate on the Force Bill. For Calhoun, any attempts to coerce a member state against its interest not only endangered that state, but also the crucial republican principle that the states were to share benefits and burdens on an equal basis.

Calhoun’s chief concern was how to restrain a tyrannical majority that had no wish to share equally the benefits and burdens of the Union. How did a political minority protect its interest if prudence, restraint, and generosity were driven out of politics? Writing to Virginia senator Littleton Tazewell in 1828, Calhoun observed that “despotism founded on combined geographic interest admits of but one remedy, a veto … on the part of the States.”

Later, in his Disquisition on Government (1851), Calhoun argued for giving each distinct interest or division in the Union a negative power over legislation harmful to it. Such a negative power, be it nullification, a veto, or interposition, would encourage compromise and harmony between the majority and minority. Calhoun’s views were informed by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions. They are still very much alive today in debates over the Second Amendment, immigration, and drug legalization; they retain a vital role in American politics.

Calhoun’s critics often reduce his political impact to a defense of slavery. But Calhoun saw the issue as part of a larger defense of American republicanism. He wrote that the Tariff of Abominations itself invited division and disunion. Nullification, interposition, the idea of the concurrent majority—all were institutional responses designed to preserve and defend the republican virtues of restraint, prudence, and the equality of the states.

His contemporaries referred to Calhoun as the “Last Roman.” It is a fitting description. The great South Carolinian championed the republican principles of courage, prudence, restraint, liberty, and shared power between the states and the central government. His personal devotion to the agrarian life linked him to the two Catos and Cicero. Caesar Augustus once remarked about Cicero that he was “a learned man and a lover of his country.” Despite the cloud of obloquy that has darkened his reputation in recent years, Calhoun is deserving of this same epitaph.

Image Credit:

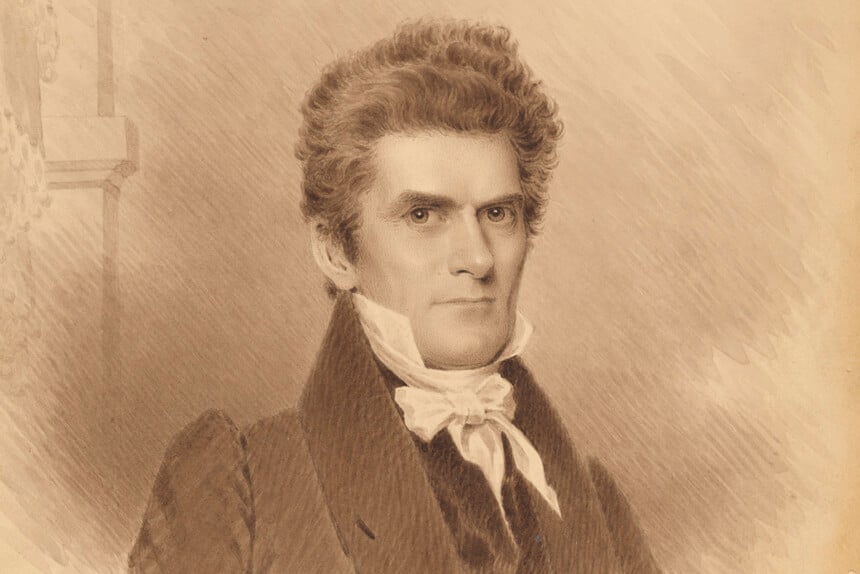

above: John Caldwell Calhoun , c. 1834, sepia ink wash and pencil on illustration board by James Barton Longacre (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

Leave a Reply