Disconnected is not an amusing book. The subtitle’s “digitally distracted” doesn’t hint at its grim findings. This short text—a long one might be too dispiriting—is nevertheless lengthy enough to expose the digital revolution as an outright calamity, though the author generally eschews the apocalyptic tone. Of course, there is the familiar boast that children now access and share information at rates undreamt of in the pre-digital world. (Information: that neutral word encompassing everything from algebraic formulae to pornographic circuses.)

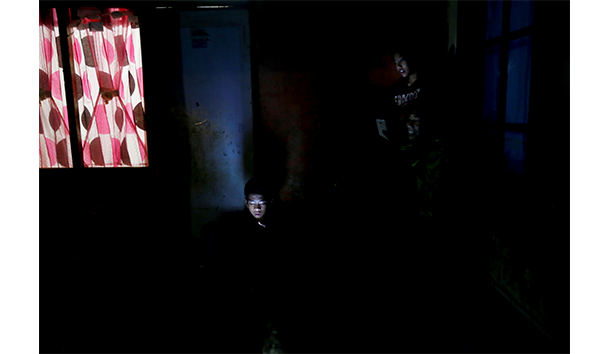

Bombarding the unformed flickering brain (researchers speak of “brains” rather than “minds,” because brains have “waves” that can be imaged in the lab) with digital information for more than eight hours a day is distracting, all right. It is also dehumanizing—again, not the author’s word.

In his Introduction, Kersting peers backward to a childhood before smartphones, a lost world where he and his friends lived outdoors in the wilds of something called a neighborhood, with no lifeline to the domestic cocoon. Rather like Dr. Livingstone on the banks of Lake Tanganyika, we presume; but the outdoor boy’s life of yore never induced sleeping sickness—or “tech-neck” and deep-vein thrombosis, old-age maladies now disturbing screen-addicted youth. Instead of restorative sleep, they are up through much of the night surfing the web, tweeting, checking their feeds and likes, and staying in touch with Facebook “friends.”

Such diversion was not available to Kersting and company. What on earth could they have found to do during all those screenless hours? They played baseball without heart protectors, football without pads; they rode bikes, without helmets. Except for school, it was a life lived alfresco, unshielded from the scrapes and contusions that a boy’s flesh is heir to. And they took these risks without the goad of “selfies” to advertise their adventures. From decades of experience as a psychotherapist and school counselor, the author suggests that, risky as the former life was, today’s indoor, sedentary, screen-buffered life may be more dangerous. And not just from overexposure to basement radon.

Kersting doesn’t fly by the seat of his pants. Almost all of his findings are supported by charts and statistics. Perhaps readers of this magazine won’t need studies to prove the self-evident, so why take this depressing statistic-freighted tour? One reason is that the “research-based” line is often the only criticism a school superintendent or tech committee will listen to; or your government-educated nieces, nephews, and children for that matter. Try referencing the insights of, say, Anthony Esolen, about the soul-deadening and mind-dulling saturation-technology in the homes and schools. The seasoned administrator will listen, tolerantly, condescendingly, as you cite a self-identified Christian social critic, however cogent, and send you away with the air of an adult reassuring a fearful child in a thunderstorm. But swat him with the findings of a Harvard Medical School research project, and you may see those long, administrative ears prick up with wary attention.

Here are some of those “research-based” findings; put away your laptops (an attention-destroyer, according to a West Point study) and take out your pads and pencils.

Starting at age 13, most teens devote eight or more hours per day (more than restorative sleep) to communing with screens. The consequence of these seances is hyperstimulation of some neural circuits, and atrophy of others. Guess what type atrophies? If you’ve ever wondered why students can’t take being “lectured to”—that is, addressed by the unenhanced human voice for more than a minute—think of those deadened circuits.

All the telltale signs of ADD, ADHD, and anxiety disorder—the current number one “epidemic” among high-school and even middle-school students—are heightened, even “caused,” by addictive use of video games, TV, Facebook, computers, and (especially) the ever-faithful “smartphone.” Human friends may desert or “dis” you on Facebook, but your smartphone will always be there for you.

Addiction may be a suspect word from its overuse as a solvent of moral responsibility. But many of the parents who, on Kersting’s advice, “disconnected” their children from devices caved under the hail of abuse, tantrums, and threats of violence and suicide. Like Frank Sinatra in The Man With the Golden Arm, few children with these golden phones have the strength to quit cold turkey.

Knowing the hazards, what is the appropriate age for giving your child one of these devices? Whenever you feel comfortable with pornography, says the researcher. For parents who believe their adolescents have no appetite for this pig’s breakfast, Kersting adds that most teens regularly erase their browsing history for a reason. By age 18, most will have seen 200,000 acts of violence. He doesn’t disclose how many sexual acts will have flickered before their eyes, but the digital age surely exceeds T.S. Eliot’s paltry “thousand sordid images” (Preludes) that constituted the soul of 1910.

But it would be a mistake to conclude that parents are invariably the hoplites in the pass, standing athwart the techno invasion. It isn’t some pusher, but the guardians themselves who lavish digital devices like the pricey smartphone on their offspring. Parents, alas, have either welcomed the screens or succumbed to them themselves.

If you can trust a California State University study, parents typically spend just “three-and-a half minutes” per week in “meaningful conversation” with their children. Three-and-a-half—not four? That sounds suspiciously precise; and “meaningful” casts further doubt on the methodology of such studies. One wonders if homey chat about a meal or a movie, a quip or a quote—amusing only to the initiate—falls in or out of the researcher’s “meaningful” category; but even admitting doubts about the kind of family that would submit to “scientific” analysis (and after Obergefell, just what do the lab coats mean by “family”?), anyone who opens his peepers in a restaurant notices the pall of silence cast over human interaction. The diner who intrudes dinner conversation courts sullen resentment. Those flat-screens on the walls, smartphones on the tables, have claimed the terrain and resent human intrusion. But even at home, on those rare occasions when the family unit chows down en bloc, “sixty-four percent” do so accompanied by TV. Does that enhance “meaningful conversation”?

Quibbles about methodology aside, there seems little cause to doubt studies that confirm what the sentient person sees and senses all around him. There is an addictive property to digital technology. As the author and his studies attest, overexposure fosters impulsivity, inattention, depression, fits of rage, and lack of coping skills; in other words, bad character.

Since picking up this little book from my local library I’ve noticed a spate of similar titles covering what is now a hot topic. Some may be better, but this is the only one you need. And it has the virtue of brevity. It’s even shorter if you skip the last chapter: “Using Mindfulness and Meditation to Reconnect Our Disconnected Kids.” After a convincing diagnosis of what he calls an “epidemic,” Kersting’s parting prescription—taking away the phones and screens before bedtime, no electronics at dinner, etc.—will seem inadequate to the disease. And some of the writer’s advice will seem downright loopy: “Walk more slowly,” “form an image . . . of success and abundance,” “stare at a picture that represents determination . . . I like to use a picture of Rocky Balboa.” And this: “Our children need to develop the faith that they are supreme beings” in order to “live up to their full potential.” After such solid sense throughout, Kersting’s parting mélange of New Age nostrums, the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, and the prosperity gospel might make you feel that you’ve been had.

Nonetheless, Kersting’s book deserves to be read. The next time the superintendent calls for a school bond issue to “enhance and update our computer labs . . . to put lap tops in the hands of every student in order to compete in the local, global, and intergalactic marketplace,” you won’t be cowed. Armed with Kersting’s data, you’ll pop this gas balloon and put the technophiles on a diet of bread and water; such restraint is better for the bottom line and—as “studies show”—for the students’ mental and emotional IQ. You might add that, as with all addictive substances, the compulsion to overindulge is especially keen in adolescents. Let their elders raise a restraining hand and stop waving the pompoms.

[Disconnected: How to Reconnect Our Digitally Distracted Kids, by Thomas Kersting (Createspace Independent Publishing Platform) 110 pp., $10.99]

Leave a Reply