MSNBC host Rachel Maddow’s history of America’s pre-World War II fascist movements vastly exaggerates their power and ignores the real nature of anti-interventionism.

Prequel: An American Fight Against Fascism

by Rachel Maddow

Crown

416 pp., $32.00

This silly, disjointed book written by an MSNBC talking head plays up the danger of a reemergence of America’s 1930s and 1940s domestic fascist movements to an absurd extent. In a wordy yet vague style characterized by an undercurrent of hysteria, Maddow harps on minor figures and matters while evading substantial issues.

Maddow’s vagueness seems to be strategic, as when she blurs the distinction between the tiny minority of actual fascists in America before World War II and the vastly more numerous population who simply opposed U.S. involvement in the war.

When Prequel actually touches serious matters forthrightly, it falls down badly. Early on, Maddow subjects the reader to a sustained rant about the alleged influence of American racial laws on the German Nazis. Nazis needed no lessons in dealing with Jews from American Jim Crow laws, and such claims ignore the well-known point that law and lawyers were not significant in the Nazi scheme of things. Hitler in particular despised lawyers (perhaps his only endearing characteristic); in his Germany, their job was to formulate rationalizations for policy, not to guide it.

Even worse, others sections show Maddow’s slight understanding of American history. She portrays Theodore Roosevelt as a wild racist and Indian-hater—an odd picture of a man who coolly enraged Southern opinion by lunching with Booker T. Washington in the White House, and wrote in a rather unprejudiced manner about American Indians in Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail. She is totally at sea in her muddled characterization of the Supreme Court’s “Insular Cases,” which assured American colonial subjects most, if not all, of the rights U.S. citizens enjoyed under the Constitution.

The real problem with Prequel is its inflating not the nastiness, but the danger posed by America’s domestic fascist movements. They just weren’t big enough. Their leaders were zoological specimens—a collection of wackos, perverts, idiots, and conmen wholly lacking the abilities of a Hitler or Mussolini. An impressive proportion wound up in the big house for financial shenanigans. In any case, the American public’s hostility to fascism would have defeated even abler men, as in Britain, where fascists were led by the vastly more impressive Oswald Mosley.

America’s fascists would have liked to do worse. Some of their movements tried to stockpile weapons and even stole them from the armed forces. Many yakked about an armed revolt after the 1940 elections, but that remained just talk. These groups were worth keeping an eye on, and Maddow is right to praise those who had the grubby job of doing just that, like the Anti-Defamation League’s Leonard Lewis and FBI agent Leon Turrou. But their surveillance of these minor groups was not nearly as important as she insists.

Maddow is particularly obsessed with their raging anti-Semitism, which she brings up repetitiously and even lasciviously. She fails to mention other quirks of these movements, some of which made them self-limiting. The largest domestic fascist group, the “Silver Shirts,” hated not just Jews but also Catholics, which cut them off from the followers of Father Coughlin, whose appeal was itself limited by the wide dislike of Catholics that still existed among Protestants in that era.

Curiously, she does not mention some of the Coughlinites’ real misdeeds; they often physically attacked Jews in some of the big Eastern cities. She does find the time to blather on about Henry Ford’s well-known anti-Semitism. But Ford’s beliefs didn’t convince many people. In the sorry last 30 years of his life, Ford’s promotion of anti-Semitic propaganda did vastly more harm to his employees, his family, and his company than to Jews.

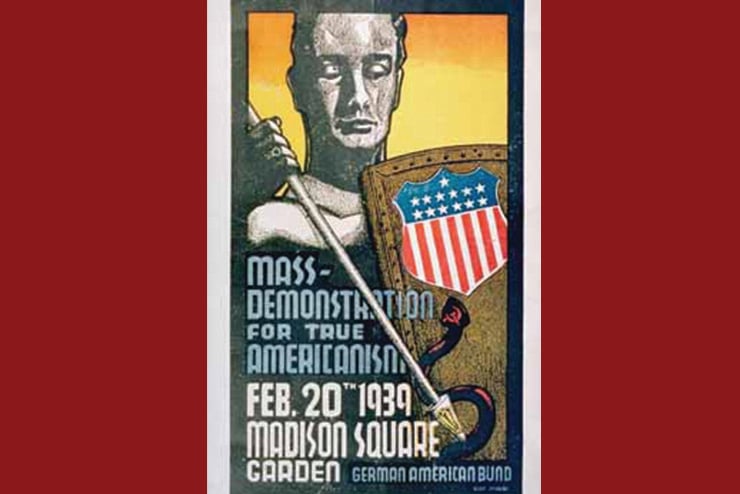

To further put things in perspective, it is useful to compare the danger of the American fascist movements with the American Communists, who Maddow mildly whitewashes. The latter were at least twice as numerous as the two largest fascist groups put together. They were a useful tool of Soviet power, but no one would seriously maintain that the danger they posed included a serious threat of taking over the United States. By comparison, Maddow rather slides over the German-American Bund, a 1930s pro-Nazi group of ethnic Germans. The Bund’s leaders were crooks and the organization was so useless that the Nazis finally conceded that their embassy in Washington was right to argue that they should be dropped. If anything, the Bund made only the slightest dent even among German-Americans and did more harm than good to the fascist cause.

Maddow further inflates the domestic fascist threat by identifying it with the Southern politician Huey Long. Long was indeed a dangerous demogogue but it is highly doubtful that he can be considered a fascist or a figure of the right. His program and actions were clearly leftist in orientation. Some fascists had great hopes for him, but they were not realistic judges.

An interesting point she does raise is the ability of some fascists to later shed their pasts, notably Philip Johnson, who was widely rated as a great architect (though people who lived or worked in the modernist buildings he designed often held a very different opinion!).

The worst fault of Prequel is its inability to deal in an honest and serious way with the anti-interventionists (called “isolationists” by their critics) and their connections with the Nazis—such as they were. Unlike the clowns in the Silver Shirts and the German-American Bund, American anti-interventionists were a serious force. At least up to the start of World War II, most Americans were indeed anti-interventionists. A majority, after the fall of France, switched to supporting a huge military buildup and the policy of all-out aid to the Allies “short of war.”

Huge majorities of Americans, while believing fatalistically that the United States would wind up entering the current war, and accepting that the Axis powers would eventually attack America if they won in Europe and Asia, did reject actually declaring war on Germany in the near term. This divided state of mind persisted right up to Pearl Harbor. An inability to grasp that reality is one of Maddow’s major weaknesses. The issue in 1940 and 1941 was not immediate entry into the war, but whether to support “all out aid short of war.” Anti-interventionists, mainly grouped in the America First organization, opposed that policy, while most of the population at that time backed it. Anti-interventionists did not want a Nazi victory and would have liked to see the British win; a minority did favor the phantom of a negotiated peace. To say, as Maddow does, that “lots” of Americans favored the Axis because of the existence of these anti-interventionist groups is ridiculous.

Worse, elsewhere, with a sort of verbal sleight of hand, Maddow tends to conflate anti-interventionists with domestic fascists. Though refraining from making the point directly, she brackets people who were patriotic and decent citizens with groups like the Silver Shirts. She refuses to seriously discuss anti-interventionist ideas or their origin, or even their political complexion. Perhaps that is because she might encounter some embarrassing facts. One is that many anti-interventionist ideas, to the extent they were not just continuations of traditional notions but were distinctive to the era between the world wars, were of liberal origin. The major liberal journals of opinion, The New Republic and The Nation, converted to interventionism only after the fall of France. Some liberals, and a majority of American Socialists, remained anti-interventionist right up to the Japanese attack, as did almost all of the Western progressives. By implication and omission, she leads her readers to assume that all anti-interventionists were right-of-center.

While expressing contempt for Charles Lindbergh, a familiar target, she neglects—or deliberately avoids—mentioning certain prominent anti-interventionists far more important and powerful than Lindbergh. Notable examples of this include the most famous labor leader of the era, John L. Lewis, who knowingly dealt with German agents, the newspaper publisher Robert McCormick, as well as congressional anti-interventionists, who sometimes served as a transmission belts for German propaganda and received funds from the Nazis. And some anti-interventionist leaders—Lewis and Hamilton Fish, knew that. But most did not; the subsidies were passed through cutouts by the German diplomat Hans Thomsen, who skillfully evaded FBI surveillance. Oddly, Maddow makes only one brief reference to Thomsen.

Other anti-interventionist leaders were sufficiently irresponsible, or deranged enough, to at least verge on treason. While excoriating Senator Burton Wheeler, Maddow strangely fails to mention his most outrageous actions: publicizing the occupation of Iceland in advance (luckily he got the date wrong!) and, just before Pearl Harbor, revealing the Victory Program, which outlined the military buildup and war production requirements. Sen. Wheeler was published by McCormick’s Chicago Tribune. Later, in 1942, the paper “let slip” that the United States was reading Japanese codes.

Finally, there was Joseph P. Kennedy. While usually dubbed an anti-interventionist, Kennedy held such extreme views that he cannot be properly classified as such—he actually sympathized with the Nazis. That his son John contributed money to the America First Committee of course also goes unmentioned by Maddow.

Leave a Reply