Forty years ago in Commentary, Ruth Gay created the American Jewish essay as an art form of dignity and eloquence, and in this wonderful book she brings her life’s work to its glorious climax in a sustained statement of remarkable purity. In the beginning, she took the raw materials of everyday life as lived by New York Jews and turned them into art—a verbal collage, really—that captured ordinary lives, while ennobling and dignifying them. (All this in a memorable essay on the Jewish delicatessen in the Bronx.) No one had written that way before, but many have tried—few with equivalent success—since.

In her new book, she portrays two generations of New York Jews: the immigrants of the beginning of this century, and their children of the middle years. What makes her writing remarkable is not just its sensitivity for evocative detail, its ability to suggest large thoughts through humble observation. It is the absence of nostalgia and sentimentality, the lack of cheapness, and the refusal to take the easy way out. Respecting her subject. Gay never patronizes or ridicules. And because her vision penetrates the heart of experience, she is incapable, as always, of condescension.

Conventional treatment of New York Jews—like that of Woody Allen, the most eloquent and ferocious Judaismhater of our day—demeans them. Or else it patronizes them through implausible idealization. Here, by contrast, we have a sustained account of the life of an immigrant milkman and his family in the Bronx: a life of near-penury and perpetual insecurity, but one of dignity and humanity—and holiness—withal.

In many ways the book is a mirror image of the other classic on the immigrant experience and that of their children, Oscar Handlin’s The Uprooted: the starting point for sustained historical research that Handlin himself pioneered. He announced then that he had set out to write the story of immigration to America, but found out that immigration was the story of America. Then in general terms, pertinent to every group, he told the tale of the immigrants and their struggle. Gay tells the same story—about Jews in the Bronx. It bears the same charge of universal interest: the particulars conveying the universal picture.

The book begins with a brief account of immigrant origins in Eastern Europe and ends by reflecting upon their experience, and that of their children, in the New World. Eastern European Jewry today is idealized, and even—owing to the emotionalism engendered by the literature of the holocaust—canonized. Gay shows the poverty, misery, and hopelessness produced by economic disaster and political catastrophe after the dissolution of Poland by Russia, Austria, and Germany that persuaded millions of people, most of them teenagers, to escape to Godless America. The shank of the book covers subjects of quotidian interest providing the occasion for profound reflection.

Ruth Gay is a woman of remarkable wisdom, which is why her book works so well. She sees much, and understands more. Throughout, she gives us insight into the traits of intensity, toughness, and candor that marked New York Jewish life.

Gay also shows the underside of candor, the brutality and chaos of human relationships, explaining why those of us born and brought up in more genteel settings and brought to New York by reason of education found life in that city at once attractive and revolting. When, from a Yankee suburb of what was then a white Protestant state capital, I came, via Harvard and Oxford, to the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, I entered a world in which everyday human relationships were brutal, envy undisguised, and gentility rare. A son of the third generation, I did not know what to make of New York Jews, who flourished in intense contention. In those days I found solace in the study of Abraham Heschel, an immigrant and a theological model, who found that world equally puzzling by reason of a quite different upbringing. He came out of the nobility of Judaism, and I came looking for that same Judaism: the one viewing with pity the works of prior immigrants and their children, the other the embodiment of Jewish immigrant life in quest of something beyond the wilderness that two generations of immigrant Jews had wrought.

Being an immigrant made for a tough life. But being an immigrant’s child presented even more intractable problems to work out. Ruth Gay makes of the encounter between generations and cultures a remarkable and ennobling story, and a well-told one besides.

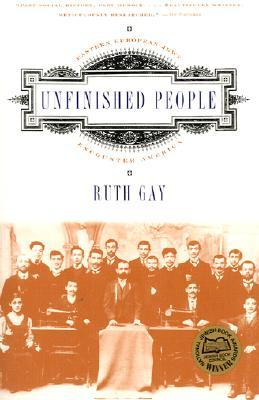

[Unfinished People: Eastern European Jews Encounter America, by Ruth Gay (New York: W.W. Norton) 310 pp., $27.50]

Leave a Reply