The rise to political prominence of former Airborne Forces General Aleksandr Lebed, and especially his emphasis on law and order as the only real basis for proceeding with reforms, has raised the specter in the Russian mind of the proverbial Man on a White Horse, the military savior whose iron-fisted rule puts the national house in order. The image is not alien to post-Soviet Russians, many of whom well remember the charge of “Bonapartism” made by Nikita Khrushchev against the popular World War II hero Marshal Zhukov. By refusing to support the August 1991 coup, however, the Soviet military effectively hastened the collapse of the communist regime (Lebed is partly credited with keeping the Airborne Forces out of the political fracas), and Yeltsin’s use of regular army troops to suppress the Supreme Soviet in October 1993 highlighted the crucial importance of military support for any prospective Russian leadership.

During the reformist era (beginning with Gorbachev and continuing today), the role of the military has been hotly debated. Military officers, civilian experts, and politicians have argued over the merits of an all-volunteer army, the structure and mission of the Russian military in the post-Cold War period, and military doctrine and strategy. The catalyst for much of this debate was the Soviet defeat in Afghanistan, which exposed the demoralized state of the army and the military’s lack of preparedness for unconventional warfare. The army command system was judged too rigid: innovation and initiative were stifled, and political ideology had often overridden common sense. The harsh and often brutal treatment of conscripts, the high peacetime casualty rates, the low pay and primitive housing conditions, and the corruption of the officer corps and the Soviet nomenklatura system became common themes in Soviet and Russian public discourse. Russian officers began to lobby for higher pay (or even to be paid at all), better living conditions, and much-needed reforms. “Committees of Soldiers’ Mothers” demanded that the state protect enlisted men from the brutal, sometimes fatal, hazing known as the dedovshina. Politicized organizations of Afghan veterans and ex-officers became commonplace. By the beginning of the postcommunist era, military participation in public life was a fact.

Having had no experience of warfare on our native soil in more than a century, Americans easily overlook or underestimate the symbolic importance of the military in Russian life. The special aura of the army and the mystical attachment between the Russian and his Fatherland was etched deeply in the popular imagination by the experience of the war against fascism. Millions died in the inferno of the Russian front; the legendary defense of Stalingrad and the march to Berlin strengthened the national bond as no other experience could. At home every man, woman, and child was mobilized, tightening the ties of blood and soil in the crucible of total war. Whatever legitimacy the communist regime would enjoy among the Russians thereafter was based largely on the sense of patriotism and nationalist fervor that the Great Patriotic War generated. Westerners may have been puzzled by Boris Yeltsin’s decision to unfurl the red banners of the victorious Soviet army during the victory day celebration in 1996, but like his predecessors in the Kremlin he recognized the importance of the banners that so many had fought under. As Yeltsin had told them before, the wartime victory had not been communism’s, and surely not the nomenklatura‘s, but the people’s. Russia’s army is a people’s army. What institution could be more likely to raise up a man of the people?

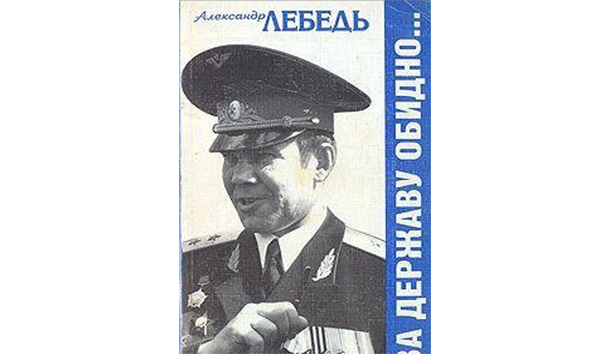

A better man of the people than Aleksandr Ivanovich Lebed, born into a worker’s family in 1950 in the Russian city of Novocherkassk, would be difficult to imagine. Tall, big-boned, and equipped with a booming bass voice, this Afghan war veteran and former heavyweight boxer (as his memoirs testify, he is not a man averse to using his fists as a management tool on occasion) is an uncommon common man whose awareness of the corruption surrounding him has been increasing throughout his adult life.

Both Lebed’s grandfather, who lived in internal exile for a number of years, and his father, who survived the Gulag only to fight in a penal battalion (considered a death sentence in itself) for the duration of the Great Patriotic War, suffered under the communists. As a boy, he witnessed the suppression of a worker’s protest in his native Novocherkassk; today he promises that, as president, he would never use the Russian army against the people, and calls the October 1993 bombardment of the Supreme Soviet “Russia’s shame.” In Afghanistan, where he commanded a battalion in 1981-82 and won the Order of the Red Star for bravery (an honor he does not mention in his book), he saw lives wasted in what he considered to be a fruitless and unwinnable war. But what did the Brezhnevite nomenklatura care? It was not their sons who would serve there, but “the sons of workers and peasants,” and the Soviet High Command forgot that the first concern of the officer must be “to return to all mothers all their sons.”

His opposition to the Chechen war (which made him very popular both with civilians and with many servicemen) was based first and foremost on his view that “such a war simply cannot be won.” Lebed was not surprised that the politicians—nomenklatura holdovers for the most part—had failed to see, as he recently told the Komsomolskaya Pravda, that the brutal application of heavy firepower there had “destroyed the homes of a large number of people with impunity, killed their relatives and friends, and maimed their children.” No wonder the Chechen resistance was so fierce, says Lebed; “you would have grabbed an assault rifle too, wouldn’t you?”

As Lebed sees it, the task of postcommunist Russian patriots is to build a Russian nation-state—the day of the empire is over in his view—that would protect the freedom and dignity of all Russians, that would end forever the rule of corrupt elites who have exploited the people, and that would nurture what talents the people themselves possess to build something for themselves and their posterity. Lebed calls his vision for Russia derzhavnost, literally “great powerness,” but his notion of what makes a great power great is markedly different from that of “red-brown” nationalists who long for the days of superpower status. Lebed has described derzhavnost in these words: “There is the citizen, a person who has on the territory of his country a family, children, a home. . . . [H]e has something to defend, something to fight for, and, if necessary, to die for. The vagrant is not given to understanding what the homeland is In wartime he disappears. . . . A man must stand on his own land, he must have something of his own.” Only men who are masters of their own land can build derzhava, a truly great Russian state.

According to the general, the army should be reorganized and designed for defensive operations, and Lebed pledges that, as president, he would never commit Russia to “holy alliances” and “world revolutions” paid for by “Russian blood . . . Russian money and Russian suffering.” Police and security forces should, under the command of the strong presidential system he wants to preserve, conduct an all-out war on the organized crime structures that are such a prominent feature of present-day Russia. The freedom and dignity that derzhavnost promises, and the self-respect that Lebed hopes Russians will come to feel, can be realized only after basic order has been established. In the end, the new Russia will be established for the good of the people, for throughout the country’s long and painful history, “Czars, General Secretaries [of the Communist Party], and presidents come and go, but the people remain.” For Lebed, only the people are “eternal.”

Since the 19th century, when both conservative Slavophiles and liberal Westernizers “went to the people” to find an uncorrupted social stratum to use as a basis for their differing versions of reform, populism in various forms has played an important role in the politics of the country. It is not surprising, then, that the perennial populist message, used to great effect by the Bolshevik revolutionaries, has become a vehicle for the activities of various politicians in postcommunist Russia. Unlike the 19th century intellectuals, however, today’s politicians go to great lengths to depict themselves as men of the people, and not merely as elite reformers.

In his autobiography Against the Grain, Boris Yeltsin presented himself as a champion of the people whom the corrupt nomenklatura turned into a “political pariah.” Yeltsin described his struggle as one against “the party bureaucracy” that was attempting “to put obstacles in the way of perestroika and glasnost.” Yeltsin, however, “drew new energy” from his contacts with ordinary citizens and saw his political career as dedicated to ensuring that “we will never again live as we did before.” Yeltsin’s efforts to meet ordinary people on their own ground—taking public transportation to work during his days as Moscow party boss, for instance—won him a reservoir of good will among the mass of Russians that has served him well.

Yeltsin’s version of populism, however, has not been the only one promoted by Russian politicians. Vladimir Zhirinovsky has been quite successful in promulgating a populist line that is rawer and more visceral than Yeltsin’s. Zhirinovsky once told Russian voters that “For years you have been deceived, made fools of, and stuffed full of various dogmas” and that only he, who had suffered as they had, could set things right. Zhirinovsky’s populism plays on envy and self-pity—and, like Yeltsin’s, has made him friends among the Russian people.

Lebed’s populism is different from either Yeltsin’s or Zhirinovsky’s, though many Russians think that the general’s outsider status makes him Yeltsin’s legitimate heir. In his memoirs, Lebed envisions the future Russia as one of “free people [living in] a free land . . . without slavery in our blood” or “fear in our genes.” His unique blend of populist, democratic, nationalist, and traditionalist themes forms a coherent worldview, unlike Yeltsin’s, but one that does not capitalize on the resentment, or indulge in either the self-pity or self-glorification, that mark Zhirinovsky’s. So far, Lebed has been able to maintain his image as the honest and incorruptible “Mr. Clean” of Russian politics. Whether or not he will remain true to himself and his notions of derzhavnost is an open question, and what becomes of him will depend as much on the Russian people—and how they see themselves—as it does on Lebed himself.

[Za Derzhavu Obidno . . . (It’s a Pity for a Great Power . . . ), by Aleksandr Lebed (Moscow: Moskovskaya Pravda) 464 pp.]

Leave a Reply