“Not only England, but every Englishman is an island.”

—Friedrich von Hardenberg

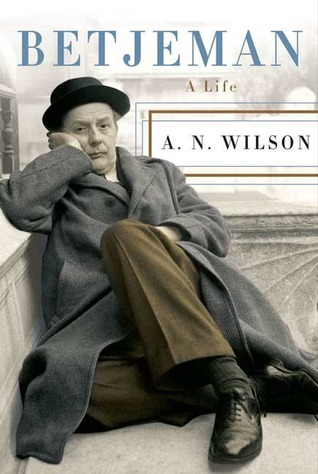

John Betjeman’s evocative and educative television programs and his uniquely readable poetry have left an indelible image in the British public mind—of a jolly, witty, and eccentric man, ambling around Britain’s cities and countryside, pointing out hitherto unnoticed details of hitherto underappreciated buildings and excoriating the dreadful devastation caused by town planners for whom anything old was axiomatically inferior. Betjeman’s frequent media appearances, with his trademark crumpled mac, battered hat, and plastic bag; his confessional interviews and articles; his patent kindliness; and his ability to laugh at himself left many Britons with the impression that they knew Betjeman personally. He was a kind of national favorite uncle (albeit one with teeth infamously “covered in green slime” and a “pong” caused by his dislike of bathing).

The publication of Andrew Norman Wilson’s long-anticipated biography of this popular figure was overshadowed by the revelation that rival biographer Bevis Hillier had hoaxed Wilson into including a love-letter purportedly written by Betjeman. The letter was cleverly written—but, taken together, the capital letters at the beginning of each of the sentences spelled out “A N Wilson is a shit,” and it was forwarded by “Eve de Harben,” an anagram for “Ever been had.” Hillier resented Wilson for calling the second volume of Hillier’s three-volume, 25-years-in-the-making Betjeman biography a “hopeless mish-mash”—and because Wilson’s biography had received prepublication publicity as “the big one.” Wilson has apparently retaliated in his own hastily produced second edition, but that covert message has yet to be revealed.

Wilson has previously written books about Jesus, Saint Paul, Belloc, C.S. Lewis, Milton, Tolstoy, Scott, the Victorians, London, and the House of Windsor, as well as some 19 novels. He also writes regular columns for newspapers. His biography of Iris Murdoch (2003) drew critical venom, with reviewers calling it, variously, “the aborted foetus of the biography he was contracted to write, pickled in a disturbing mixture of regret, nostalgia and distaste”; “a nasty, hasty piece of work, pockmarked with gratuitous insults, unprovable anecdotes and cruel asides”; and “misguided, treacherous and inessential.” One critic noted, “[Wilson] seems to thrive on . . . negative energy: the radioactive fission of feud and betrayal.” Mercifully, he is also capable of making deft character judgments, and of viewing Betjeman in his true colors and context.

Betjeman was born into a middle-class family in north London. His father was the proprietor of a third-generation, high-end furniture-making business founded by Anglo-German forebears in the 18th century. They were never close, although Betjeman recorded that his father had read Goldsmith’s Deserted Village to him as a boy, with considerable formative effect. Betjeman’s refusal to follow his father into the family firm (“Uninteresting then it seemed to me, / Uninteresting still”) was a source of friction and of lifelong guilt for Betjeman. In his 1960 blank-verse autobiography Summoned by Bells, he was still dwelling on his father’s reaction:

I see his kind grey eyes look woundedly at mine,

I see his workmen getting other jobs,

And that red granite obelisk that marks

The family grave in Highgate Cemetery

Points an accusing finger to the sky.

His childhood was characterized by acute consciousness of his middle-class (and, to a lesser extent, partly non-English) origins, at a time when class gradations were infinitely more important in English life than they are today. He was often lonely and gloomy, and had a precocious interest in religion, poetry, and the past. His blue moods were leavened by larky humor and intermingled with numinous outbursts inspired by finding congenial souls, uncovering rural survivals in suburban London, exploring old churches, and holidaying in his beloved Cornwall.

He attended Marlborough, which he tended to dislike, then went up to Oxford in 1925, where his tutors included C.S. Lewis, whom he also disliked at the time. Like many a predecessor, he found socializing more enjoyable than study and was eventually sent down for failing in Divinity—an ironical failure for a man who spent so much of his free time in churches. He subsequently became a teacher in a small private school near London—somewhat fraudulently, as the job required proficiency in cricket. (Betjeman was always unfit, although he famously admired sporty girls with “strong legs.”)

A life-changing break came in 1930, when Betjeman was recruited to write for Architectural Review. An early interest in the theories of Le Corbusier soon changed into a devotion to older buildings, especially Victorian ones. Even in the 30’s, thousands of these buildings were being lost every year without anyone really noticing, let alone caring. He hated to see vast new buildings for a newly mobile, “mass man” age—department stores, bus stations, petrol stations, government buildings, factories, “Tudorbethan” flats and houses—being built where, within his memory, there had been old buildings or open fields.

He rapidly made a name for himself as a campaigning journalist and as an authority on the threatened highways and byways of English landscapes and townscapes. Although not all of his campaigns succeeded, he was instrumental in the rescue of such architectural legacies as the Arts and Crafts suburb of Bedford Park in west London and the St. Pancras Hotel at King’s Cross. By 1933, he had become general editor of the new Shell Guides, with which he was associated until 1966. Issued by the oil company as a marketing tool, these much-admired topographical works encouraged mass motoring, which, Wilson points out acidly, had the ironical effect of helping to ruin the very places they featured.

That same year, he married a field marshal’s daughter, Penelope Chetwode, whose mother commented acerbically, “We invite such people to our houses, but we don’t marry them.” Penelope and Betjeman had a son, Paul, and a daughter, Candida, but he was far from being a perfect paterfamilias. Betjeman’s offhand treatment of his son curiously mirrored Ernest Betjeman’s treatment of him—and Paul’s later conversion to Mormonism was also a curious reprise of John’s search for religion in a coldly material world.

He spent 1939-41 working for the Ministry of Information, and 1941-43 as the British press attaché in Dublin. There is a story that the IRA had planned to kill him but that the assassin charged with the task had decided against doing so because, having read some of Betjeman’s poetry, he decided he “couldn’t be much of a spy.”

After spending 1943-45 at the Admiralty, he and Penelope moved to an 18th-century rectory in Berkshire, where one of their first actions was to remove a bathroom because it was out of keeping. Betjeman’s refusal to tolerate aesthetically displeasing “mod cons” ensured that the house was uncomfortable all year round. It was for such reasons that his friend Anthony Powell described Betjeman as having a “whim of iron.”

Betjeman worked for the British Council after the war, before getting involved with the BBC. He was a “telly” natural, and TV work soon became a kind of compulsion. He even went as far as Australia to make films, although he didn’t much like traveling. (“Abroad is so nasty. I would rather die in Wolverhampton than Aix-la-Chapelle.”) In between times, he produced a regular stream of articles and poetry. In 1960, he was awarded the title Commander of the British Empire. He was knighted in 1969, became poet laureate in 1972, and received numerous honorary degrees and literary honours.

In 1972, Betjeman started to experience health problems and began a long and quietly courageous battle with Parkinson’s disease. Toward the end, he gave televised interviews in which he regretted both that he had not had enough sex and that his religious faith was so shaky. He died in Cornwall in May 1984 and was buried near Trebetherick in the churchyard of St. Enodoc’s.

Wilson, a former candidate for Anglican ordination, is fascinated by Betjeman’s waxing and waning religiosity. Throughout his life, Betjeman seesawed between deep faith in what he called “the Management” and deep doubt, as expressed at the end of his poem “In Willesden Churchyard”:

My flesh, to dissolution nearer now

Than yours, which is so milky white and soft,

Frightens me, though the Blessed Sacrament

Not ten yards off in Willesden parish church

Glows with the present immanence of God.

Like many Anglicans, Betjeman was always as much interested in the props of religion—the history, the buildings, the congregations, the vestments, the liturgy, the music, the cadences of the Book of Common Prayer—as in the truth of the Christian message. For him, Anglicanism became a central requirement of English scenery and identity, and of his own identity. (“Religion fitted him like an old slipper,” Wilson observes neatly.) He never really forgave his wife for converting to Catholicism in 1947. He saw a specifically English God in specifically English suburban settings, just as William Blake saw angels in the trees at Peckham Rye. Religion was both a crutch to support him against looming decrepitude and death, and a source of feelings of inadequacy—especially in respect of his lusts and lapses, most importantly his 30-year extramarital affair with Elizabeth Cavendish, sister of the duke of Devonshire. His combination of understated patriotism and a dislike of religious dogmatism are exceedingly English.

What is it about Betjeman’s poetry that makes it simultaneously risible to the “intelligentsia” (although Philip Larkin, Evelyn Waugh, R.S. Thomas, and John Piper were Betjeman fans, to name just a few), yet so hugely appealing to the general public? It has to be said that Betjeman sometimes is more poetaster than poet. A good example of his not trying very hard is cited by Wilson: “Dear Mary, / Yes, it will be bliss / To go with you by train to Diss.” This is perilously close to Mac-Gonagallism. Yet even the worst poems contain sincere emotions and good lines, and far from being “nasty and hasty,” Wilson gives credit where credit is due. (He, incidentally, is not incapable of writing such sentences as “the sea off these dramatic cliffs [of North Cornwall] is not man’s friend.”)

The poet’s lasting popularity is owing simply to the fact that, as Wilson puts it, “At some visceral level, [Betjeman] speaks for England.” It is not just his appealing “telly” persona but his comforting subject matter: class, public school, varsity, eccentric lords and dons and vicars, sprawling suburbs, Victorian villas, golf clubs, dusty Nonconformist chapels, empty Anglican churches, gentle religious doubts, ghost stories, seaside holidays, quiet countryside, youthful bicycle rides, birthday parties, muffins, tea and—not least—what Wilson calls “feelings of abject love and longing.”

All of these homely subjects are described without artifice, yet also without condescension—besprinkled with brand names we all know or have heard, described in a pleasing voice littered with archaic pronunciations (“goff” instead of golf, “otel” for hotel), and fragrant with memories of old hopes and disappointments, like the lingering smell of perfume in a long-emptied bottle. And behind all the massed detail is the evident vulnerability of a man who combined everyday overconfidence with existential terror.

In “By the Ninth Green, St Enodoc,” Betjeman wonders of childhood memories, “Why is it that a sunlit second sticks?” It sticks because some detail—a new color, smell, or sound, or an unexpected angle—fixes it forever in our minds. Betjeman’s adroit manipulation of details makes his poems stick in our minds. Soon, we start to feel that he is telling us about our own memories. He is a Boswell for the middle-class Everyman.

The poems are also full of “death, and failure, and disappointment, and greed.” Wilson cites Betjeman’s imagined English pensioners living on the Costa Blanca: “Our savings gone, we climb the stony path. / Back to the house with scorpions in the bath.” There is a world of sere despair in those lines. Betjeman’s generic good humor did not preclude hatred for the tawdriness, mean-spiritedness, and money-grubbing of modern Britain. He loathed seeing “toilets where the cattle stood” (“Delectable Duchy”). He apostrophized “Inexpensive Progress”: “Encase your legs in nylons, / Bestride your hills with pylons / O, age without a soul.” He excoriated modern farming: “We spray the fields and scatter / The poison on the ground” (“Harvest Hymn”). Rhetoric of this kind will always appeal to the English, in whom romantic longings for a bucolic, prelapsarian past run deeply.

Betjeman’s writings are also gilded with the ineffable magic of that now almost completely eclipsed England of grand aristocratic houses combined with a vital middle-class culture of moral rectitude, Italianate villas with names like “Windy Ridge” and their own gravel drives and privet hedges, where lived pretty girls with double-barreled names who were the objects of Betjeman’s usually unavailing, usually unexpressed passions. Such subjects were always bound to alienate the sort of person who feels that England is boring and bland and that such everyday, established things are beneath notice. For Betjeman, wisdom was always “humble love for what we sought and knew” (Summoned by Bells). Those who poured contempt on his work were searching for very different things and seeking to distance themselves from what they already knew and should have loved much better.

His ecological and architectural concerns now seem mainstream (thanks, in part, to his own efforts and those of others such as James Lees-Milne), but, at the time, he and they were ridiculed by the same “intelligentsia” who were then busily facilitating the mass immigration, multiculturalism, family breakdown, punitive taxation, transfer of national independence to the European Union, and wanton destruction of beauty that have now all but extinguished England.

Many members of this “intelligentsia” also resented the fact that Betjeman never joined in their various moral spasms. While they were concerning themselves with Franco’s Spain, anticolonialism, civil rights, nuclear disarmament, vegetarianism, or the iniquity of sex discrimination, Betjeman was campaigning on behalf of threatened cemeteries and terraces, or rhapsodizing about bossy girls “furnished and burnished by Aldershot sun.” He never promoted any ideology, but took people and things at their face value and on their own terms.

Betjeman always hated easy answers and the prigs who proffered them. In the 1920’s, when many of his peers were parading their nonbelief, he was on his knees seeking absolution in chapels, churches, and Quaker meeting places. When they were aspiring downward and seeking “solidarity” with the purportedly downtrodden, Betjeman aspired upward instead. He always liked to strike attitudes and maintain friendships (with aristocrats, or with the Mosleys—although he disliked fascism, calling Mosley’s chief ideologue, Alexander Raven-Thompson, “Alexander Raving Looney”) that flouted received collective opinion. Hugo Williams puts it well in his Introduction to Faber’s new selection of Betjeman’s poetry, Poet to Poet: “Instead of a manifesto we get the whole man.”

When they were expressed at all, Betjeman’s political ideals were always conveyed subtly, as in “Death of King George V,” whose generation was composed, in the poet’s eyes, of “Old men who never cheated, never doubted”—a generation succeeded by that of Edward VIII, whose style is typified by his arrival “At the new suburb stretched beyond the run-way / Where a young man lands hatless from the air.” In this masterfully restrained poem is expressed Betjeman’s generic distrust of change, whether political, cultural, or aesthetic—this change exemplified by the mean buildings surrounding Croydon aerodrome (then London’s airport). Edward’s not wearing a hat gives the irresistible inference that he—or, at least, his relatively informal generation—is not really to be trusted.

The final compulsive ingredient in the Betjeman broth, bubbling up like a spring through everything he wrote, is irrepressible good humor. Millions of Britons share the memory of his round impish face as he imagines what a prim English lady in twinset and pearls might be reading (the worst kind of slangy American detective story), or can picture him as he stands, drink in hand, laughing for eternity in a bosky garden, as seen on the dust jacket of this book. For Betjeman, laughter was always his saving grace. He once made the Chestertonian remark that “no real mirth is possible without the apprehension of the mysteries as its antecedent.” For him, the sacred and the profane became increasingly intermingled—and gentle fun, a means of keeping the gathering darkness at bay. In “The Last Laugh,” he pleaded:

I made hay while the sun shone.

My work sold.

Now, if the harvest is over

And the world cold,

Give me the bonus of laughter

As I lose hold.

All in all, it is easy to see why John Betjeman should be a latter-day English icon, honored as much for his universal insights as for his quiet commitment to England, home, and beauty. It is pleasing to think that, through A.N. Wilson’s insightful and accessible biography, future generations may be summoned by Betjeman to the defense of their still beautiful and now even more beleaguered homeland.

[Betjeman: A Life, by A.N. Wilson (London: Hutchinson Press) 375 pp., $27.00]

Leave a Reply