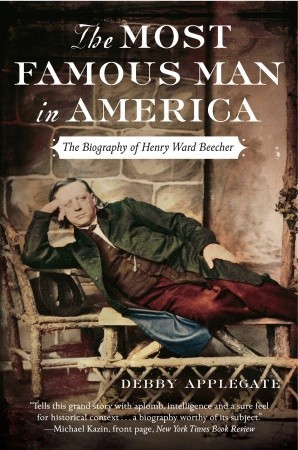

Debby Applegate’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Most Famous Man in America: The Biography of Henry Ward Beecher, treats a wide range of subjects: religion, politics, social upheaval, war, and clerical sex scandals. And, while such a list might sound as if it were referring to contemporary America, the events recounted here occurred a century-and-a-half ago. In chronicling Beecher’s life, Applegate, a professor of American studies at Yale and Wesleyan Universities, brings to light the era Beecher helped shape and makes clear to the astute reader that his influence remains with us today.

A son of the Rev. Lyman Beecher, a well-known Congregationalist preacher and professor, Henry Ward Beecher (1813-87) possessed impressive oratorical skills. He was pastor of one of the largest churches of his day, Brooklyn’s famous Plymouth Church, as well as a key spokesman for the antislavery cause. And he preached the so-called Gospel of Love, which placed him on the cutting edge of 19th-century liberal Protestantism. In many ways, Beecher was progenitor of the socioreligious phenomenon that would eventually be called the “mega-church” movement.

Beecher was reared a strict New England Congregationalist. However, the rigidity of his upbringing was challenged by two factors: an insatiable need for love (owing partly to the death of his mother when he was three years old) and his family’s migration to the less religiously restrictive Midwestern frontier, when his father became head of Lane Theological Seminary near Cincinnati. From these conflicting personal currents would emerge a highly personalized doctrine that was light on theology, sketchy on the consequences of sin, and heavy on individual and social concerns. Beecher’s pulpit prowess, his belief in Herbert Spencer’s concept of “evolutionary meliorism,” and his proclamation of the nonthreatening Gospel of Love made him an international cause célèbre. The effectiveness of his message can be attributed to its timeliness. It found rich soil in America’s broadening democratic ethos and the rise of pragmatism in the 19th century.

The election of Andrew Jackson in 1829 brought to a close the limited republic of philosopher-statesmen envisioned by America’s Founding Fathers, as the growth of raw democracy that broadened the voting franchise weakened traditional social hierarchies, including the hold that established religions had on the people. It opened the door to the rise of populist faiths, such as Methodism, which were based less on dogma and more on sentimentalism and ministering to emotional needs. This religion grew rapidly in the developing Midwest, where Henry Ward Beecher spent the early years of his ministry.

Beecher’s entrepreneurial instincts and pragmatic approach to life enabled him to borrow from Methodism and to adapt his church’s message and style of worship accordingly. He built his ministry not on orthodox Christian doctrine (which includes such disturbing dogmas as Original Sin and Hell) but on what he perceived people wanted to hear—the empathetic “personalism” that the market for religious ideas was demanding. As Applegate puts it, Beecher’s message was successful because “he was so aware of the world’s alienation and pain.” Such a “grassroots” approach to religion encourages an easy adaptability, away from theological truths and toward societal problems and personal needs. It greatly enhances the power of charismatic preachers, since it offers “cheap grace” in the form of quick solutions to life’s most vexing challenges. For evidence, we need only reflect on the influence wielded by today’s star preachers, such as Joel Osteen, Rick Warren, and T.D. Jakes—all of whom are Beecher’s spiritual heirs.

Populist religion also gravitates toward politics. Abraham Lincoln recognized Beecher’s stance against slavery as a valuable asset to his own presidential ambitions, visiting Beecher’s church as a candidate and, later, courting him at the White House. In appreciation of Beecher’s support during the Civil War, Lincoln gave him the honor of delivering the keynote address at the reclamation of Fort Sumter in 1865.

Beecher realized the personal value of getting along with those in power, adjusting his loyalties to his own advantage. For example, despite his strong and vocal opposition to slavery, after Lincoln’s assassination, Beecher supported the retrogressive President Andrew Johnson (1865-69). And, in 1885, he switched his allegiance to the party of the Democracy and Grover Cleveland, whose election all but ended federal efforts to ensure freed slaves the rights conferred by the 14th and 15th Amendments. How could Beecher have been so flexible? Applegate’s answer is simply that he enjoyed the prestige and the patronage that came from associating with those in political power. In some ways, Beecher anticipated the multiparty relationships maintained in our own time by the Rev. Billy Graham, who, though certainly not a moral pragmatist, has managed to get along with every president since Eisenhower.

Beecher had serious character flaws, in addition to his apparent fascination with political power. Allegations of marital infidelity clouded the later years of his ministry; indeed, they command too many pages of this book. Applegate’s account does provide some worthwhile insights into sexual exploitation by the clergy, however. The personal magnetism, verbal mesmerism, and kindly manner exerted by a gifted pastor inevitably garner a certain number of female admirers—a dynamic that has accounted for the fall of many clergymen. In Beecher’s case, it led to a trial for adultery, and both his behavior and the testimony he gave are indicative of an acute ability to compartmentalize and prevaricate. In addition, his manic accumulation of material goods suggests an inner emptiness.

Noticeably missing from the story of Beecher’s later life is any mention of the devotional prayer to which he was given in his younger years. This apparent lack of an interior prayer life may be best attributed to his loss of faith in a personal God. Perhaps this was the cause of his decline in moral discipline and his willingness to compromise pastoral moral standards that should be above reproach. In this area, Applegate lets Beecher off too easily. Her comparison of his shortcomings with those of John F. Kennedy, Bill Clinton, and Martin Luther King, Jr., makes it seem as if she is excusing all these men on psychological grounds—which may indicate an acquiescence on her part in the present culture that extols candor and doubts the ability of men to practice virtue.

With the 2008 presidential-primary campaigns already under way, American church leaders have another opportunity to speak out on the subject of personal morality as well as on current political issues. Unfortunately, the thinking that Beecher worked so hard to promote—and which persists today—encourages pastoral focus on the latter, but not the former.

[The Most Famous Man in America: The Biography of Henry Ward Beecher, by Debby Applegate (New York: Doubleday) 544 pp., $27.95]

Leave a Reply