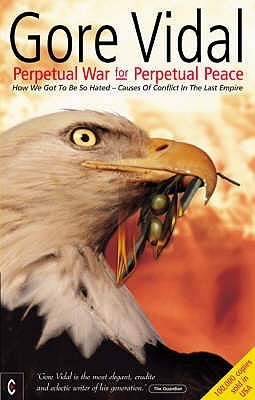

Gore Vidal, award-winning essayist, novelist, and playwright, has been a keen observer of American culture and politics for several decades. Yet when he originally submitted to major American magazines of opinion the essay that forms the first chapter of his new book, Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace, he found himself completely shut out. No one wanted to publish his point of view or, indeed, much of anything that defied the government line—straight out of the Madeleine Albright Book of Inanities—that America had been attacked because some people just hate democracy.

Jang, the leading Pakistani daily, summed up the state of official opinion in the United States at the time:

Not a single media commentary from the United States has hinted at a critical appreciation of the country’s foreign policy. Only one statement is being repeated, that the terrorism against America will be responded to and the terrorists will be crushed.

But any intelligent person must at least be curious about what motivates the type of savagery we observed on September 11, and most people are surely capable of making the elementary distinction between explaining an event and excusing it. When such questions are posed, however, our ruling class offers us “responses that ought not to satisfy a second-grader,” as Pat Buchanan recently put it.

The title of Vidal’s book is somewhat misleading, since just over a quarter of the text is devoted to American foreign policy and September 11. A great deal of the book involves the Timothy McVeigh case—a shame, since Vidal’s take on the war on terrorism is currently of much greater import. Still, it is worth reading Vidal’s analysis of the McVeigh saga, which includes a discussion of the provocations that have brought about the profound alienation of a considerable minority of Americans (e.g., the patriot and militia movements), a brief outline of McVeigh’s personal history, and an interesting analysis of what Vidal shows to be an investigation almost criminal in its ineptitude.

The connection between Oklahoma City and September 11, according to Vidal, is that, while each atrocity is obviously inexcusable and morally despicable, both cases involve especially excitable people who believe that the actions of the U.S. government justified their conduct.

“Since I am a loyal American,” Vidal says of September 11, “I am not supposed to tell you why this has taken place, but then it is not usual for us to examine why anything happens; we simply accuse others of motiveless malignity.” None of the standard explanations make much sense, he adds, but

our rulers for more than half a century have made sure that we are never to be told the truth about anything that our government has done to other people, not to mention, in McVeigh’s case, our own.

All Americans get is a ceaseless stream of stories about “mad Osama and cowardly McVeigh,” thereby “convincing most Americans that only a couple of freaks would ever dare strike at a nation that sees itself as close to perfection as any human society can come.”

Since the end of the Cold War, some excellent foreign-policy analysis has come from writers who associate themselves with the left—Edward Said and Alexander Cockburn, for example. In Vidal’s book, though, his leftism pops up here and there, and on some questions, especially his warnings about a phantom “far right” in America, his opinions turn out to be drearily conventional and mainstream.

Thus, in an unintentionally funny chapter called “The New Theocrats,” Vidal goes after the Southern Baptists, whose announcement of a boycott of the Disney company sounds to him rather like “a pretrial deposition from Salem’s glory days.” I expect a little more nuance from a “distinguished man of letters,” as Vidal is usually described. Calling the almost pathetically timid Christian Right “theocrats” when much of what they advocate amounts to the perfectly American desire to be left alone borders on the hysterical. The grassroots of the Christian Right consist of basically decent folk doing the best they can in a world virulently hostile to basic norms of behavior that previous generations took for granted. Vidal calls upon Disney to “throw the full weight of its wealth at the Baptists, who need a lesson in constitutional law they will not soon forget.” He suggests bringing this gaggle of would-be tyrants up on charges of “restraint of trade” and deplores the chilling effect that such a boycott would have on free speech.

Why, in a free society, people should not be allowed to exercise a voluntary campaign of abstention from patronizing a firm whose product they (and, with them, the entire world two generations ago) find repulsive is left unclear. But Vidal insists that we must, at all costs, prevent these Christians from establishing a theocratic hold over our society, an outcome about as likely as a restoration of the Stuarts. For a man who goes to such effort to plumb the depths of Timothy McVeigh’s soul, Vidal is ludicrously hostile toward a group of normal Americans whom he makes no comparable effort to understand.

Vidal refers—in passing, and not very originally—to Newt Gingrich’s pathetically toothless 1994 Contract With America as the Contract on America. Again, I would expect a great man of letters to be able to see the obvious: Gingrich’s “Contract” signified once and for all the end of any serious conservative opposition to the federal apparatus, which it left almost completely untouched. Elsewhere, he lashes out at something he calls the “Roman Catholic far right,” despite the fact that there is obviously no far right anywhere on the American political scene. Again, most of the conservative Catholic positions to which Vidal doubtless objects are matters of morality that were fairly mainstream a mere two generations ago. It has since become “far right” to believe what everyone’s parents once took for granted. To be sure, former FBI Director Louis Freeh has plenty to answer for, but most sinister in Vidal’s eyes is that he belonged to Opus Dei, a conservative Catholic organization that Vidal calls “an absolutist religious order.” He finds it “most disturbing” that such a figure should hold such a high office in our secular United States. (I do not recall spending many anguished nights fretting about the imminent Christianization of the U.S.A. via the FBI.)

Despite my criticisms, which admittedly deal with only minor portions of the book, Vidal’s work is almost infinitely more thoughtful and worthwhile than the condescending banalities of William Bennett, whose Why We Fight: Moral Clarity and the War on Terrorism suggests that even to look for the motives of the September 11 attackers constitutes “relativism” and a crime against God and country. Vidal is only saying what Buchanan has already said: Terrorism is the price of empire.

Having read Hilaire Belloc, I am well aware of the argument that the Muslim world may never reconcile itself to a program of peaceful coexistence with the “Christian” West and that even a serious effort to tame the American empire would not necessarily put an end to terrorism. But the United States enjoyed a great deal of prestige and good will in the Middle East during the early 20th century, from the end of World War I until Harry Truman’s fateful decision to cast America’s lot with Israel. The Middle Eastern states that were carved out of the defunct Ottoman Empire, assigned as League of Nations mandates to France and Britain, overwhelmingly favored being governed as mandates by the United States.

It is dramatically urgent that the point of view Vidal expresses in Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace gain as much exposure as possible, for it constitutes the essential rejoinder to the neoconservatives, who refuse to learn any lessons from anything or to consider giving up on empire and letting us live as a normal country again. Vidal concludes: “We have allowed our institutions to be taken over in the name of a globalized American empire that is totally alien in concept to anything our founders had in mind.” Every time forbidden opinions like Vidal’s find their way into print, the Old Republic scores a limited victory. Whether the cogency of Vidal’s position is enough to break through the ignorance and complacency that bred the American Empire in the first place remains to be seen.

[Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace: How We Got to Be So Hated, by Gore Vidal (New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press) 160 pp., $10.00]

Leave a Reply