Charles Hamilton Houston, dean of the Howard Law School, taught his students to view law as an instrument of social engineering, and Thurgood Marshall, one of Houston’s top students in the early 1950’s, never forgot this basic lesson. As a leading advocate in the nation, Marshall served as a catalyst for social change as he led the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education.

Mark Tushnet charts Marshall’s career post-NAACP. Though he recounts the life of Marshall the judge rather than Marshall the advocate, the reader quickly learns that the two are separated only by a black robe. Marshall never wore the so-called judicial mask, permitting him to decide a case based on law rather than personal beliefs. To the very end. Marshall remained Dean Houston’s social engineer. Tushnet, who served as Marshall’s law clerk, is to be commended for the honesty in his account of his former boss’s time on the Supreme Court. Except for a minor lapse when discussing affirmative action, the author never pretends Marshall was anything but a social engineer who invented the necessary law when he perceived a societal problem. This short book covers much ground and unintentionally highlights what is wrong with modern American jurisprudence.

Tushnet begins his book with Marshall’s appointment to Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, the most prestigious appellate court in the nation at the time. President Kennedy originally wanted to appoint Marshall to a district court, but Marshall held out for a larger feather in his cap. He could not have been more unsuited for the Second Circuit, since 90 percent of the court’s business concerned corporate law—an area in which Marshall had no experience. Tushnet describes Marshall’s performance as “unspectacular.”

Lack of experience hindered Marshall in his next position as well. In 1965, after four years on the Court of Appeals, Thurgood Marshall was appointed Solicitor General of the United States. Tushnet recounts one case involving business law in which Marshall responded to questions from Justice Abe Fortas by reading answers that a staff attorney sitting next to him had just written out. when Fortas demanded that Marshall explain an answer, the Solicitor General replied, “I am handing them up to you just as fast as I get them.” Such a stellar performance apparently convinced LBJ that Marshall was well suited for the Supreme Court. Marshall’s appointment to the Court was confirmed by the Senate in August 1967.

Tushnet describes the Supreme Court in 1967 as the right place for Thurgood Marshall and at the right time—a time when the justices saw themselves as a branch of “a coordinated national government dedicated to reducing economic disparities.” These liberal justices “no longer felt attracted to the general theory of judicial restraint. As they saw things, a big Court was a natural part of a big government.” As for Marshall’s personal philosophy of the law, it seems much akin to his storytelling. “As a storyteller,” writes Tushnet, “Marshall was not above modifying his account of real events a bit to give his stories a better punch line.” So too with the Constitution. Marshall fervently believed that a judge who identified a pressing social problem could invent the necessary constitutional law to go along.

Such a philosophy is evident in Marshall’s dissenting opinion in Dandridge v. Williams, where he argued that Maryland denied a welfare recipient the equal protection of the laws by imposing an upper limit on welfare payments, thus allowing the recipient $250 when he “needed” $296. The majority refused to second-guess state officials charged with allocating limited funds, and Marshall criticized “the Court’s emasculation of the Equal Protection Clause as a constitutional principle.” During his years on the High Court, Marshall adroitly used a sliding scale of equal protection analysis to uphold laws he fancied by applying to them a low level of scrutiny, and in turn striking down laws he objected to by using a higher standard. By his reliance on the sliding scale, he found it easier to discuss public policy in the manner of a super- legislator rather than that of a judge interpreting the law. Unfortunately, Marshall’s equal protection methodology is alive and well in the Supreme Court today.

After examining Marshall’s equal protection theory, Tushnet inadvertently exposes the Justice’s hypocrisy regarding affirmative action, saying Marshall “simply asked the court to respect legislative choices.” Marshall, so he claims, only looked to see if the corporate body was within its powers when it enacted the program. In this way Marshall comes across as some sort of states’ rights champion who cried foul when an overreaching majority of the Court struck down affirmative action programs. What both Marshall and Tushnet seem to have missed is that with Brown, which Marshall argued in front of the Court, the days of judges deferring to legislative choices and ignoring their own views came to a close. Constitutional law had been moving steadily in that direction, and Thurgood Marshall—with the help of Earl Warren—formally ushered in a new era of activism and consolidation. Fittingly, some affirmative action programs later died by the judicial sword Thurgood Marshall was so instrumental in fashioning.

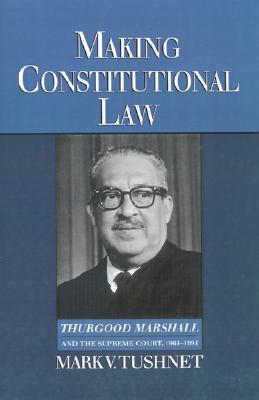

[Making Constitutional Law: Thurgood Marshall and the Supreme Court, 1961-1991, by Mark V. Tushnet (New York: Oxford University Press) 256 pp., $29.95]

Leave a Reply