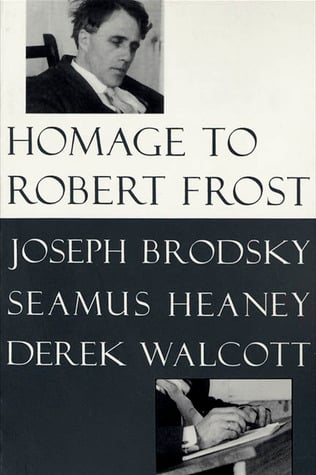

A poet’s critical prose holds interest for many people. Scholars examine it for clarifications or contradictions of the poet’s verse, admiring readers for echoes of the language that captivated them in the poetry, to which students and new readers may want some kind of “authorized introduction.” When writing about the work of others poets reveal as much, or more, about themselves and their own work. These three essays by Seamus Heaney, Derek Walcott, and the late Joseph Brodsky, gathered in Homage to Robert Frost, remind us why we should trust poets more than most critics when it comes to discussing the art.

“Among major poets of the English language in this century,” Heaney observes, “Robert Frost is the one who takes the most punishment.” Much of this brief volume’s appeal lies in its unabashed praise for Frost’s achievement. It continues the attempts of William Pritchard and a few others to rescue the poet from the grotesqueries of his biographer, Lawrance Thompson, and the kind of portentous generalizations launched by Lionel Trilling upon the occasion of Frost’s 80th birthday, when he pronounced Frost “the most terrifying poet of our time.”

It is not just that poets—these three in particular—provide an inside view, a practitioner’s insight into Frost’s colloquial tone or his handling of meter. The initial delight of these essays is, as Frost himself might have said, in their own sound, the aptness and pleasure of their own phrase-making. What academic critic these days would credit Frost’s “jocular vehemence” as Brodsky does? Or observe, as does Heaney, the “lovely pliant grace” of “Birches” or confess to a “lifetime of pleasure in Frost’s poems as events in language, flaunts and vaunts full of projective force and deliquescent backwash, the crestings of a tide that lifts all spirits.” Over and over, as when Walcott describes the “melodious sarcasm” of Frost’s dramatic monologues, we are reminded that, analytical as they are, these essays are essentially appreciations rather than arguments. Refreshingly, the only axes to grind belong to Frost’s laconic New Englanders.

Another advantage of these essays is concentration. Each takes up only two or three poems, focusing on the metrical tension of a certain line or the consonantal echo throughout a given stanza. This devotion to particulars pays greater homage to Frost than any of the formulas to which we are accustomed by now. Moreover, by attending to some of the less-anthologized and less-remarked poems, Homage to Robert Frost renews our interest and satisfaction in the poetry instead of merely confirming its greatness (or its darkness, or its “terror”).

The essay-discussions overlap slightly, making the overall effect almost that of a panel. What repetition there is comes as something of a glance down the row, as if with a familiar nod Walcott were referring to a comment made a while earlier. For example, when early on in Heaney’s essay he declares that Frost “never shirked the bleakness of that last place in himself,” he seems to echo a point made just a few pages earlier by Brodsky: “If this poem [“Home Burial”] is dark, darker still is the mind of its maker. . . . He stands outside, denied re-entry, perhaps not coveting it at all.”

Taking the essays individually, we not only find things in Frost we may have missed or forgotten; we also learn a great deal about what animates three contemporary poets, the kinds of verbal textures and angles of vision that excite each one in turn. Each pays homage to that element in Robert Frost which perhaps best limns his own work.

Thus Brodsky’s piece, “On Grief and Reason,” dwells on the bleakness of Frost’s sensibility—a focus we might expect from the late Russian poet who once defined the writing of poetry as “an exercise in dying.” With nicely telling irony, Brodsky begins by analyzing the poem “Come In” and concludes with “Home Burial.” The former becomes for him a “humble footnote or postscript” to Dante’s Commedia, a “stylistic choice in ruling out a major form,” as the poem’s speaker doubly refuses the invitation:

Far in the pillared dark

Thrush music went—

Almost like a call to come in

To the dark and lament.

But no, I was out for stars:

I would not come in.

I meant not even if asked,

And I hadn’t been.

Such poems, Brodsky points out, are full of set-ups, what Walcott calls “traps.” In “Home Burial” the husband mounts the stairs to answer for himself what he has asked his wife: “She let him look, sure that he wouldn’t see, / Blind creature; and awhile he didn’t see. / But at last he murmured, ‘Oh,’ and again, ‘Oh.'” Of course, as Brodsky points out, several more lines of this couple’s dialogue will pass before the reader discovers what there is to see out that window. The tension, the low simmering suspense in the characters’ words and gestures, can be found in countless other Frost poems, not just the dramatic monologues or narratives. Brodsky may plead a bit too much for this poem as a retelling of the Pygmalion-Galathea myth, but such a reading has its compelling features and at any rate forces us to examine all the more closely the pair’s situation.

For Seamus Heaney, Frost’s poetry is a “defense against emptiness.” Moving well beyond his own paraphrase of Frost’s famous definition of poetry as a “momentary stay against confusion,” Heaney attends to matters of form in such poems as “Desert Places” and “Birches.” Both illustrate Heaney’s (and Frost’s) distinction between craft and technique, between what can be picked up or learned about making verse and what is somehow intrinsically a function of one’s own voice, one’s stance or attitude toward life. Heaney plainly admires Frost’s ability to create the “slippage toward panic” in the opening cadences of “Desert Places” and the “airy vernal daring” of “Birches.” At such moments, Heaney’s commentary actually assists—as literary criticism was surely meant to—the effect of the poem under discussion. The poem, Heaney says, is an “emotional occurrence, yet it is preeminently a rhythmic one, an animation via the ear of the whole nervous apparatus.”

“The Road Taken,” Derek Walcott’s contribution to the volume, originally appeared as a review of the 1995 Library of America edition of the Collected Poems, Prose, & Plays. For this reason, the essay ranges a bit wider than either Brodsky’s or Heaney’s, while losing nothing of their directness and acuity. Walcott’s assessment could well be subtitled “Frost the Modernist,” placing the poet’s innovations with “sentence sounds” among the experiments of William Carlos Williams and e.e. cummings. We are reminded that Pound and Yeats approved of the freshness and vigor of the early poems; but Frost carried out the injunction to “make it new” without, for example, endorsing the “variable foot” or resorting to verbal pyrotechnics.

We are amazed at the ordinariness, even the banality, of Frost’s rhymes (“bird”/”heard”), at the courage, even the gall, of the poet, rubbing such worn-out coins again but somehow polishing them to a surprising sheen. This directness has danger in it. . . . But Frost’s power lies in the ease with which he slides over his endings with the calm, natural authority of a wave or a gust of wind, making his rhymes, with apparent diffidence, a part of the elements, of poetry and of weather.

For this reason Frost’s achievement is often undervalued or even dismissed, especially by the trendier academic critics. That three of our era’s most renowned poets—Nobel Laureates all—should feel they owe to Frost such professional gratitude and appreciation should recall for us the sources of poetry’s power, its movement (as Frost put it) from delight to wisdom. It should not be lost on us, either, in this age of earnest multiculturalism, that the poets gathered in Homage to Robert Frost hail from Russia, Ireland, and the West Indies, respectively. As Walcott writes here, a “great poem is a state of raceless, sexless, timeless grace.” That we would not find such a sentiment expressed by many of our current literary critics is reason enough to read the poets instead.

[Homage to Robert Frost, by Joseph Brodsky, Seamus Heaney, and Derek Walcott (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux) 117 pp., $18.00]

Leave a Reply