A book about the love of baseball obsessed with the sport’s alleged racial sins, and which dare not utter the old name of the team from Cleveland.

Why We Love Baseball: A History in 50 Moments

by Joe Posnanski

Dutton

400 pp., $14.99

Baseball and other sports can operate as mythologies. This is especially true in societies where more traditional mythologies—those connected to religion or to the society itself and its people—are intentionally diluted by those hostile to more primordial mythologies.

I am a child of the 1970s. Sport mythology was an intrinsic element in my conception of self and the meaning of life. I grew up in an irreligious home, as is true of a fraction of Americans that began increasing in the second half of the 20th century and has not ceased growing. Mythology as it has been offered to the young forever, in stories of sacred figures in religious narratives or heroes in tales of national birth and struggle, was still present in the America of my childhood. But myth attached to sport and other popular culture—music, television, and film stars especially—was growing in the absence of any effort to maintain the traditional hierarchy of such stories, i.e., with religion and national pride being superior to sports.

Sports stars populated my youth, particularly those in baseball, which was then America’s Game. I can recall virtually every inning of the ’75 World Series. It was the first I saw, and it featured the local Cincinnati Reds and Boston’s Red Sox in a seven-game drama for the ages. A few years later, I marveled at Reggie Jackson hitting three home runs on three first pitches in a decisive ’77 World Series game. I am still capable of repeating nearly exactly (and with a better than average impersonation) the commentary by Howard Cosell at each blast. So naturally, Joe Posnanski grabbed my attention with his Why We Love Baseball: A History in 50 Moments. Posnanski even includes events from that ’75 Series and Jackson’s feat among his 50 moments.

Of course, things are different now. As with so many other things in American life, the woke virus has relentlessly infected Major League Baseball and nearly all of American professional sports. The league paraded its players, just as the NBA and NFL did, in Black Lives Matter regalia during the 2020 George Floyd riots. The players’ association, the owners, seemingly everyone affiliated in any way with Major League Baseball marched in feverish lockstep, repeating the required mantras in the wake of the Chauvin verdict.

This did not prevent the media sentinels of woke totalitarianism from noticing that baseball’s response, however slavish its contour, was not quite as lightning quick as that of professional football and basketball. The latter two sports have solid majority black player populations, while baseball (as the race-obsessed never tire of noticing) is less than 10 percent black.

The New York Times published an angry June 2020 column that perfectly illustrated the comic level of attention to virtue signaling by our country’s elites. Its author, James Wagner, breathlessly reminded his readers that “M.L.B.’s first public statement on the matter did not come until 10:29 a.m. on Wednesday—nine days after Floyd’s death.” Picture the entire cultural establishment with their stopwatches out to neurotically note when everyone chimes in with the correct political sentiments about officially recognized important matters and you will have an accurate view of the insane destination at which we have arrived in America today.

It is something of a surprise that Posnanski does not make more of the Floyd Revolution in his book, given how significant the evidence is that he is a member of the ideological cult that made and sustains it. He misses no opportunity to tell his readers how much he is in tune with the recent politically motivated explosion of interest in the Negro Leagues. The culminating moment of the 50 in his book is a series of them that focuses morbidly on race.

In these vignettes, Posnanski gets out his sackcloth and ashes and mournfully chants the litany of baseball’s historic racist sins. The legendary Tris Speaker was “a bigot … known to spend much of his free time talking about the Civil War, which he called ‘The War of Northern Aggression.’” Posnanski cites the first black MLB pitcher absurdly claiming that in the 1970s there was still a widespread public belief that blacks cannot pitch. Hank Aaron is quoted wishing for the existence of a place in which no one had ever even heard of Babe Ruth (who was rumored to be mixed race).

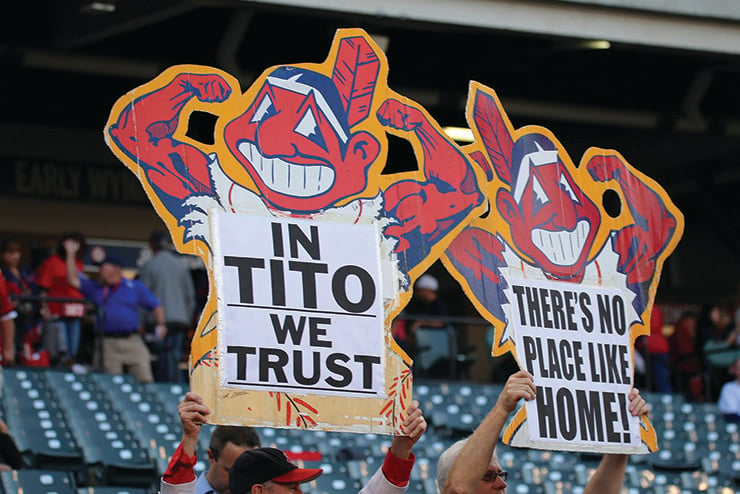

This all comes at the end of the book, but the astute reader will have learned early in its pages where Posnanski sits on the political compass. In his first moment, the author, a native of Cleveland, discusses his childhood worship of Duane Kuiper. Kuiper played a mediocre second base in the second half of the 1970s for the professional team in Cleveland, which was then called (get out your smelling salts) the Indians. In the story of his adoration of a member of the Cleveland Indians, he very deliberately avoids ever saying the name of the team on which Kuiper played. Instead, we get formulations such as “He was second baseman for my hometown Cleveland ballclub … a sizable crowd for Cleveland baseball in those days.”

Posnanski is so meticulous in his adherence to the taboo of the name of the team he loved as a kid because contemporary cultural radicals have turned the name into an epithet. This is notwithstanding the fact that there is not the slightest bit of evidence that the team’s name was anything but a means of revering what it named. Why would one name a team something you hate and expect others to hate, when the goal is to encourage fan identification with the team? This basic question seems never to occur to members of the woke cult.

To be fair, Posnanski does utter the unutterable “I” word in passing once or twice later in the book, but it is telling that he avoids it here, in his tale of his own personal and emotional ties to the professional baseball team from Cleveland that had that name in his youth. Elsewhere, he has asserted, without evidence, that the changing of the Cleveland team’s name from Naps to Indians had nothing to do with honoring a former Cleveland player, Louis Sockalexis, who was Native American. No, this was only an effort to “dehumanize” that group, Posnanski writes. Sockalexis is in the club’s Hall of Fame and has a plaque erected in his honor in the ballpark where they still play. A strange kind of dehumanization, indeed.

Here is a question that would not leave me as I was reading Posnanski: What would be at the top of the 50 moments if baseball were a mythology of real moral substance?

Perhaps we might expect to see there accounts of Elmer Gedeon and Harry O’Neill. Gedeon, who played in the outfield, had only three hits in his 15 major league at-bats, while O’Neill, a catcher, played in but one game and did not ever get to the plate at all. Pretty meager stuff for heroes? Yes, until you include that they were the only two MLB players who died during military service in World War II. Gedeon was shot down in a bomber over France, and O’Neill was killed by a sniper at Iwo Jima.

What about Rick Monday, who had served in the Marine Corps Reserve, saving the flag from radicals who tried to burn it in the outfield at Dodger Stadium in 1976, and Tommy Lasorda having to be restrained from kicking their rear ends?

Or we might get a few more words about Roberto Clemente, whose exploits on the diamond are well known and sampled in this book. I admit I immediately ran to my computer after reading Posnanski’s account of the two incredible outfield throws he made in the 1971 World Series and watched them with awe. But Clemente’s mythology extends well beyond what he did on the field. He was a fervent Catholic who died young endeavoring to use his wealth to help those suffering from a natural disaster. Aid Clemente had organized for earthquake victims in Nicaragua was confiscated by government officials instead of being distributed to those in need. Clemente responded by accompanying one of the planes to try to personally convince local officials to do the right thing. The craft was overloaded and went down near Puerto Rico on New Year’s Eve 1972. Clemente’s body was never recovered.

Posnanski clearly admires Clemente’s baseball skills, as do I. But he would have done better to open his analysis to include the most admirable things about him.

Professional baseball players themselves may still lean away from left cultural radicalism to a greater degree than athletes in some other sports, but the landscape in which they operate has changed fundamentally. The owners and the league for which they play have almost entirely collapsed before the woke idols.

I will always wistfully remember my youthful time immersed in baseball mythology. But I stopped paying attention to professional sports decades ago, as adult life intervened. My decision was also motivated by the realization that the realm of sport has become infected by the same noxious politics that has diseased our entire popular culture.

Much as I enjoyed the nostalgia of some of Posnanski’s book, I cannot help but feel moral concern at the idea of grown American men still so obsessed with the exploits of a professional athletic class that is now just another elite disconnected from the average American’s concerns. There are American men whose politics lean in the direction of healthy reinvigoration of our culture and who are profoundly handicapped in their action toward this goal by their mental enslavement to a sporting world that has voted enthusiastically for the erasure of traditional America.

I do not see how a compromise on this point is possible.

Leave a Reply