“Poetry is the Devil’s wine.”

—St. Augustine

In his prophetic poem “The Silence of the Poets,” Dana Gioia imagines a time in the not too distant future when poetry will be a completely lost art. “A few observers voiced their mild regret / about another picturesque, unprofitable craft / that progress had irrevocably doomed.” It will not be possible, however, to judge what we have lost. Out of pure nostalgia, a few old men might visit the abandoned libraries to run their hands across the spines of the neglected books; “but no one ever comes to read / or would know how.” Like most visions of the future, the situation Gioia describes is an extrapolation based on present trends. If poetry once seemed central to civilization, it has now gone the way of opera and ballet, becoming the property of an insular subculture. Paradoxically, we live in a time when more poetry is being written and less of it read than in any previous era.

Part of the blame may lie with “advances” in entertainment technology. Today, Papa is likely to celebrate the children’s hour not by reading Longfellow but by dropping a Disney tape into the VGR. Movies, television, and popular music now serve the function that poetry once served in society. Perhaps for that reason, so few contemporary poets even try to reach the mass audience enjoyed by Longfellow or Tennyson in the 19th century. But literary modernism itself may also have deliberately limited the audience for poetry even before popular entertainment began posing serious competition.

By design, high modernist poetry is difficult and elliptical. In purifying the dialect of the tribe, modernist poets abandoned a public language for a private vision. Although a poem must always be more than its paraphrasable prose content, there is a sense in which it must be understood at a prose level if it is to be appreciated at any level. Unlike instrumental music, poetry is composed of words as well as sounds. It is no accident that the last truly great American poet to be widely read was Robert Frost. Not only did Frost’s verse retain a surface accessibility shunned by the high modernists, it adhered to a conventional prosody that made individual lines and phrases supremely memorable. According to his most famous critical aphorism, writing free verse is “like playing tennis without a net.”

The publication of two recent volumes of poetry provides an occasion for pondering both the Frost legacy and the future of verse in America. The first is Charles Edward Eaton’s 13th collection of poems. The Fox and I. Eaton studied with Frost at Harvard from 1938 to 1940, and the two remained friends for the rest of Frost’s life. Eaton credits Frost with helping to launch his career, and his earliest poems seem to have been influenced by Frost’s work. As his career progressed, however, Eaton began to sound less like Frost and more like Wallace Stevens. His later poems, particularly those in The Fox and I, are highly fused imaginative constructs, far removed from what Stevens called the “quotidian.”

In the decades when American poetry was moving toward more open forms and more personal subject matter, Charles Edward Eaton maintained a loyalty to traditional forms and impersonal themes. Such steadfastness (some would say stagnation) is not characteristic of Eaton’s generation of poets. Robert Lowell (who was a year younger than Eaton) began his career writing formal verse highly influenced by the Southern New Critics, only to adopt freer forms and more confessional content in his later and better known work. A similar development occurred in the verse of Robert Penn Warren, who was 11 years older than Eaton, and James Wright, who was 11 years younger. As Thomas Swiss noted in reviewing Eaton’s New and Selected Poems (1987) for the Sewanee Review, Eaton “is more likely to write about art or animals than the people he has known. When he does write about people, it is usually in a generalized way. . . . His characters tend to be types, examples in the poem to explore ideas and themes ranging from asceticism to human greed and lust.” Although sensuality is a frequent topic in Eaton’s poems, it is a sensuality recollected in tranquillity.

The second poem in The Fox and I, “African Afternoons,” is a typically Eatonian treatment of passion. The poem seems to compare a bored lover with a big-game hunter who has tired of his sport and longs only for “a time of lying down beneath the trees with nothing thrilling left to do.” His woman, however, is like the lioness who will rise “golden, burnished, from the tallest grass,” whether he wants her to or not. The African metaphor helps to convey the sense of conflict, danger, and exasperation that are all latent in the relationship of this man and woman. But the metaphor also distances us from an immediate apprehension of these emotions. An additional distance is effected by Eaton’s reference to the lover in the second rather than the first person. Still, we think we understand what is going on, until we get to the last stanza where we discover that “you” is not a satiated hunter, after all, but “still the unfed cub who needs some practice as a lover.”

Wallace Stevens’ influence on Eaton’s vision is evident in “Antinomies for Vulcan.” The poem begins in the imperative mood:

Put a bronze nude in a room

that is red.Red walls, red rug, carnations

on a table.So that it says to anyone too

white of mind: Drop dead.

If Frost and Stevens have been obvious influences on Eaton’s career, his identity as a Southerner suggests that he may also have been influenced by the Nashville Fugitives. He has written perceptively and sympathetically about Donald Davidson, while the style, tone, and diction of his verse bespeak an affinity with Allen Tate. Like the Fugitives, at least in their “New Critical” phase, Eaton seems to admire the metaphysical poet’s use of the controlling metaphor. Often Eaton employs this device with grace and tact. (One thinks of his comparison of a porch swing and a Venetian gondola in “Front Porch Glider.”) On occasion, however, the comparison will be so strained as to remind one of the metaphysical conceit at its worst. Eaton’s equation of a redneck with a book, complete with ink for blood, falls into this category.

Because of his craftsmanship, his integrity, and his sheer productivity in a career that has spanned more than five decades, Charles Edward Eaton has earned the respect of fellow poets and the praise of thoughtful critics. He has won several prizes, and his work continues to appear in a wide variety of magazines, including Chronicles. At the same time, Eaton’s virtues are not ones that are likely to attract a large audience for his verse or to expand the diminishing audience for poetry in general. Joseph Epstein once described W. Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage as “the best nineteenth-century novel written well into the twentieth century.” Charles Edward Eaton may yet produce the best early modernist verse to be written well into the 21st century.

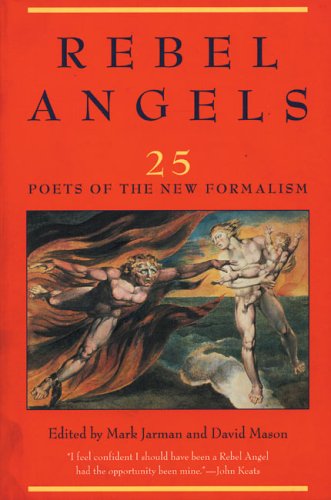

If American poetry is even to have a future in the 21st century, its direction is likely to be influenced by the contributors to Rebel Angels: 25 Poets of the New Formalism. The first question one might ask upon picking up this volume is: “What is new about the new formalism?” Even as free verse was coming to dominate American poetry in the years after World War II, a few older poets were continuing to write in traditional forms. In their preface to Rebel Angels, Mark Jarman and David Mason cite J.V. Cunningham, Anthony Hecht, Howard Nemerov, Richard Wilbur, X.J. Kennedy, and Mona Van Duyn. (One could add Charles Edward Eaton to the list.) If these paleoformalists are conservative in having held their ground against changing literary fashions, the younger new formalists are reactionary in having laid claim to an older patrimony. None of the 25 “Rebel Angels” was born before 1940, while the youngest (Rachel Wetzsteon) turns 30 this year. “Not only was the America they inhabited radically different from that of the 30’s and 40’s,” write Jarman and Mason, “but the literature that surrounded them had few ties to tradition. . . . Young poets were schooled to be unschooled. Learning and artifice were regarded as politically suspect matters. American poetry had entered another romantic phase, like a late adolescence.”

While the Rebel Angels are united by their use of formal prosody, they are too diverse in subject matter and sensibility to constitute a movement in the same sense that the Imaginists and Fugitives did. There are actually several different trends and impulses subsumed under the rubric of the new formalism. Poets such as Julia Alvarez and Marilyn Hacker might be classified as confessional poets who use traditional forms to convey very personal emotions. Even those new formalists who are not obviously autobiographical shun the indirection and reserve that we associate with modernist aesthetics. It would seem that no topic is too indecorous to be legislated out of poetry. Among those included in this volume are mastectomies, orgasms (both faked and real), oral sex, various communicable diseases, crucifixion, hemorrhoids, and flatulence. (Tom Disch’s “The Rapist’s Villanelle” may be the ultimate title of a new formalist poem.) In the verse of Raphael Campo and Marilyn Hacker, the homoerotic muse is in overdrive.

Along with the confessional formalists, one finds narrative poets such as Frederick Turner, Andrew Hudgins, Dana Gioia, Mary Jo Salter, and Sydney Lea. Although Rebel Angels is too crowded a volume to accommodate Turner’s longer narratives (he is represented here by three short poems), the storytelling skills of the other narrativists are shown to good advantage. In “Saints and Strangers,” Andrew Hudgins paints a surprisingly sympathetic portrait of an evangelist from the perspective of his daughter. (Hudgins has also written a book-length narrative treatment of the Civil War and its aftermath.) Dana Gioia’s “Counting the Children,” which was recently choreographed by a San Francisco dance company, tells the story of a Chinese-American accountant who stands outside his daughter’s bedroom door contemplating “the loneliness that we call love.” (The autobiographical expectation is so deeply ingrained in contemporary poetry that readers often ask Gioia how old his daughter is now.) Sydney Lea’s “The Feud” depicts a spat between neighbors, which escalates incrementally from farce to tragedy. Finally, in “Frost at Midnight,” Mary Jo Salter has written an impressive blank verse character sketch of Robert Frost.

Tom Disch and R.S. Gwynn are probably the most conspicuous representatives of a third movement within the new formalism—the recovery of verse sahre. Disch’s “Zewhyexary,” composed of couplets written in anapestic tetrameter, is a tour de force that takes us through the alphabet backwards: “Z is the Zenith from which we decline, / While Y is the Yelp as you’re twisting your spine” all the way through to “A could be anything. A is unknown.” (One can see why Disch is also an accomplished writer for children.) This is followed immediately by “A Bookmark,” an English sonnet about the four-year tedium of trying to read Proust’s masterwork. The poem concludes: “How I was looking forward to the day / I would be able to forgive, at last, / And to forget Remembrance of Things Past.”

One of the most original poems in Rebel Angels is an inspired bit of plagiarism—R.S. Gwynn’s “Approaching a Significant Birthday, He Peruses The Norton Anthology of Poetry.” Gwynn has created a kind of verse collage by lifting famous lines from English poetry and arranging them so they come out in alternating rhymed quatrains of iambic pentameter. The final stanza conveys its general quality:

Downward to darkness on

extended wings,Break, break break, on thy

cold gray stones, O sea.And tell sad stories of the death

of kings,I do not think that they will sing

to me.

Gwynn is good enough to redeem that most maligned of tropes, the pun. For example, the word “philistine” can refer to the peoples of ancient Philistia, who staged epic battles with the Hebrews throughout much of the Old Testament. But it can also mean a banal middleclass sensibility. In his poem “Among Philistines,” Gwynn manages to have it both ways by telling the story of Samson and Delilah as if it were happening in our contemporary culture of Action News, tabloid exposes, and Hollywood blockbusters. The contrast between present-day vulgarity and ancient myth has been a staple of modern poetry since at least The Waste Land, but rarely has the point been made with such telling humor. Metrical form (again rhyming quatrains of iambic pentameter) is an ideal vehicle for Gwynn’s wit. Consider, for example, the following lines:

Her perfect breasts, her hips and

slender waistMatchless among the centerfolds

of Zion,Which summoned to his tongue

the mingled tasteOf honey oozing from the rotted

lion.

In a sense, the effective pun is simply a telescoped instance of what the New Critics call the ambiguity of poetic language. We find another brilliant example of this device in Greg Williamson’s “The Counterfeiter.” On the surface, this poem describes a criminal artisan who prints fake money in his basement; however, the tale soon becomes a meditation on the nature of art itself. Although the perfection of the counterfeiter’s craft would lie in complete anonymity, normal human vanity prompts him to include some signature mistake (e.g., reversing the flag above the White House roof) in every bill he prints. Given the connotative richness of his subject matter and controlling metaphor, the pun at the end of Williamson’s second stanza seems natural and apt. Describing the counterfeiter’s living quarters, he writes: “In the den, above two ebony giraffes, / Hangs the first dollar that he ever made.”

A fourth tradition within the new formalism can be traced back to the redoubtable anti-romantic Yvor Winters. Essentially a dualist. Winters insisted on both rational content and metrical form in poetry. According to Gerald Graff, Winters believed that “such devices as poetic meter, rhythm, and syntax are more than mere technical apparatus; they are a kind of spiritual grammar which, like a person’s characteristic gestures and facial expressions, reflects his whole disposition toward the world. It followed from this that literary form is ‘moral’ in Winters’s sense—a judgment as to how the world is to be understood and dealt with.” The Winters legacy was passed on, in what Dana Gioia describes as a kind of apostolic succession, by J.V. Cunningham at Brandeis and by Donald Stanford at the Southern Review. Although the only representative of that legacy in Rebel Angels is Timothy Steele, one can find it to a notable degree in the work of two Southern poets not included in the anthology—David Middleton of Thibodaux, Louisiana, and the late John Finlay.

If people can be judged in part by the quality of their enemies, the new formalists have been particularly blessed. Diane Wakoski (author of “Dancing on the Grave of a Son of a Bitch” and other poems of feminist rage) has denounced them as un-American and Eurocentric for having renounced the free verse tradition of Whitman and Williams. (Does this mean that Longfellow and Frost were not real American poets?) In an attempt to infer political motives in the reversion to form, Wakoski sneers at “this new generation coming along which cannot deal with anxiety of any sort and thus wants a secure set of formulas and rules, whether it be for verse forms or how to cure the national deficit.” Waxing apoplectic, she even calls John Hollander “Satan.” This would seem to be the inside joke behind the tide “Rebel Angels.” One suspects that, unlike Satan’s hordes in Paradise Lost, the new formalists are out to displace false gods.

Because of the sheer diversity of the new formalism, one need not endorse or reject it in its entirety. Those who find confessional poetry to be exhibitionist and self-regarding are not likely to think it any less so when it is written in meters. Some of the poems in Rebel Angels seem facile and trivial, and the selection of certain contributors appears to have been motivated more by affirmative action than by considerations of merit. A book of the same length that included the work of no more than a dozen poets would have allowed a more generous selection of the best neo-formalist verse. Even at its present dimensions, one questions giving more space to Marilyn Hacker than to Dana Gioia. Such quibbles notwithstanding, Rebel Angles is an important and valuable book. (Its index of verse forms also increases its usefulness as a textbook.) By once again making song and story central to the art of poetry, the new formalists are helping to restore that art to its ancient function. Those who care about the fate of our culture must secretly be of the devil’s party.

[The Fox and I, by Charles Edward Eaton (Cranbury: Cornwall Books) 120 pp., $18.95]

[Rebel Angels: 25 Poets of the New Formalism, edited by Mark Jarman and David Mason (Brownsville: Storyline Press) 259 pp., $25.00]

Leave a Reply