Jon Meacham, editor of Newsweek, portrays Andrew Jackson as one of America’s transformational presidents, including him in the company of Lincoln and the two Roosevelts. He highlights the crucial events that took place during the 17th president’s two terms in office (1829-37), maintaining that three of those incidents effectively define him. The first (and foremost) was Jackson’s repudiation of an attempt by South Carolina to nullify the federal tariff, which the state’s leaders believed to be detrimental to the South.

Jackson saw the move as an attack on the Union. His Unionist commitment was summed up in a retort to John C. Calhoun’s toast at the Democratic Jefferson Day Banquet in 1830. Calhoun offered the sentiment, “The Union, next to our liberties, the most dear.” Jackson raised his glass to the words, “Our Federal Union; it must be preserved.”

The second incident was Jackson’s veto of a bill that renewed the charter for the Second Bank of the United States. This was the first time a president used the veto for political purposes, rather than because he deemed a bill unconstitutional. The third key event was his signing of the Indian Removal Act (1830), by which Jackson brutally forced the removal of the southern Indian tribes west of the Mississippi.

Andrew Jackson was a lone surviving orphan; he had no children; and his wife, Rachel, had died shortly before he assumed office. From those facts the author infers a psychological need for familial support. He shows how Jackson created a “family” from his circle of shirttail relatives, viewing himself as paterfamilias.

However, Meacham fails to mine the limitations in Jackson’s broad understanding of his extended national family, particularly when it came to Indians and slaves. Jackson’s sentiments toward those two groups were inconsistent with those of his six predecessors, all of whom gave at least lip service to fair dealings with the Native Americans and personally expressed discomfort with the institution of slavery. This failure may reflect some reluctance on Meacham’s part to cast his subject in an unflattering light.

Jackson’s ersatz clan comprised Major Andrew Jackson Donelson (a nephew of Jackson’s late wife); Donelson’s wife, Emily; Andrew Jackson, Jr. (another nephew of Rachel), whom he legally adopted; and Andrew Jr.’s wife, Sarah, along with the children of both couples. Jackson demanded intense loyalty, which he returned in kind. An example of his fealty to those close to him was his stubborn support for his longtime friend, Secretary of War John Eaton, despite the questionable character of Eaton’s wife, Margaret, which caused Jackson considerable trouble with the Donelsons, as well as with the Washington social set.

Expansion of the franchise during the 1820’s encouraged a new popularization of the presidency. Jackson was elected because he received widespread support from the uneducated and nonpropertied masses. This emboldened him to govern by appealing directly to the people. Alexis de Tocqueville, who was visiting the United States during Jackson’s tenure as president, presciently observed that the result of this democratic broadening was mediocrity in public life, removing the country far from the aristocracy of virtue envisioned by the Founding Fathers:

General Jackson, whom the Americans have twice elected to the head of their Government, is a man of violent temper and mediocre talents; no one circumstance in the whole course of his career ever proved that he is qualified to govern a free people, and indeed the majority of the enlightened classes of the Union has always been opposed to him. But he was raised to the Presidency, and had been maintained in the lofty station, solely by the recollection of a victory which he gained twenty years ago under the walls of New Orleans, a victory which was, however, a very ordinary achievement.

Tocqueville’s assessment of Jackson is consistent with the sociological facts of the day, yet it is completely ignored by Meacham. The strength of Jackson’s populist appeal enabled him to blur the constitutionally established separation of powers, and it encouraged Congress to shirk its responsibilities in the face of executive aggression.

In many ways Jackson was an elitist. Writes Tocqueville, “General Jackson appears to me, if I may use the American expressions, to be a Federalist by taste, and a Republican by calculation.” This insight is vitally important to understanding Jackson. But it is a point Meacham misses, and the book suffers because of it. For example, Jackson showed complete disregard for the law when he imposed martial law in New Orleans during the War of 1812. He carried this high-handedness into the White House when he illegally took federal deposits out of the Second Bank of the United States and put them in state banks. This was accomplished over the objections of his own Treasury secretary, and it caused Jackson to be censured by the Senate.

Jackson’s hatred of the Bank was both ideological and political—a form of revenge on the banking interests that had opposed his election. It was also a matter of pandering to the masses with promises of a more equitable distribution of the nation’s wealth, which he claimed was controlled by an unpopular minority (bankers or Wall Street executives). This is the stuff of demagoguery—the kind of thing leaders such as Jackson resort to effectively. They apply personal charisma to forge a program and package it as a popular call for change. Upon closer examination, however, the change they urge is often self-serving. Jackson and other “transformational” presidents have used their popularity to ride roughshod over the Constitution, to subdue the Congress, and to remake America according to their own lights.

Meacham might have written American Lion as an apologia for the current president. The similarities between Jackson and Obama—their charisma, populism, focus on redistribution of wealth, and promise of change—are uncannily striking. Meacham’s encomiastic treatment, minus any analyses of Jackson’s dark side and criticism for his programs, may limit the value of this book.

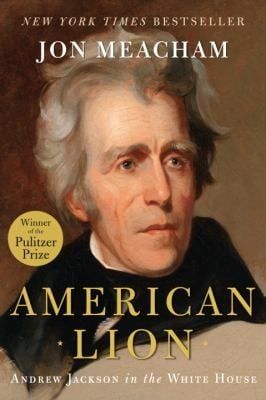

[American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House, by Jon Meacham (New York: Random House) 512 pp., $35.00]

Leave a Reply