Long ago, a British veteran of World War II offered this sober moral judgment on the war:

It was just such a sunny, breezy Mediterranean day two years before when he read of the Russo-German alliance, when a decade of shame seemed to be ending in light and reason, when the enemy was plain in view, huge and hateful, all disguise cast off; the modern age in arms.

Now that hallucination was dissolved, like the whales and turtles on the voyage from Crete, and he was back after less than two years’ pilgrimage in a Holy Land of illusion in the old ambiguous world, where priests were spies and gallant friends proved traitors and his country was led blundering into dishonour.

The occasion for the disillusionment of the hero of Evelyn Waugh’s masterful World War II trilogy was, of course, news of the alliance between Great Britain and the Soviet Union. But most Anglo-American historians lack the moral sense of Waugh, whose service in Yugoslavia allowed him to see firsthand the type of “allies” the West was helping to bring to power throughout Eastern Europe and who realized that an alliance with Soviet Russia would inevitably stain the honor of America and Britain. Instead, most Anglo-American historians subscribe to what Norman Davies terms the “Allied Scheme of History,” which is marked by “The ideology of ‘anti-fascism,’ in which the Second World War . . . is perceived as ‘the War against Fascism’ and as the defining event in the triumph of Good over Evil,” “[a] demonological fascination with Germany,” an “[i]ndulgent, romanticized view of . . . the Soviet Union,” “[t]he unspoken acceptance of the division of Europe into Eastern and Western spheres,” and “[t]he studied neglect of all facts which do not add credence to the above.” According to Davies, this view “was the natural residue of a state of affairs where allied soldiers could be formally arrested for saying that Hitler and Stalin ‘are equally evil.’”

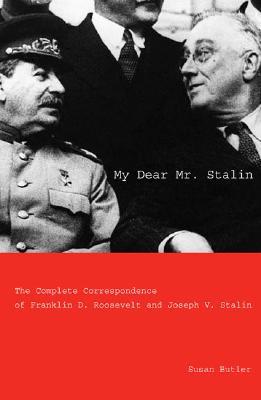

At least in intent, Susan Butler’s collection of the complete correspondence of Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin falls squarely in the Allied Scheme of History. The book is dedicated to the “405,000 Americans and 27,000,000 Russians who died in World War II.” Her dedication, however, fails to mention the two million people deported from eastern Poland, the Baltic States, and Rumania in 1939 and 1940 to die in the Gulag; the seven million Soviet citizens killed in the camps during World War II; the million POWs (including Finns and Poles) killed by the Soviets during World War II; or the million members of minority nationalities, such as the Volga Germans and Crimean Tatars, who perished in the Gulag during the war, not to mention the five to six million who died there following World War II after being repatriated (sometimes with British and American help) from territory that had been occupied by the Nazis. Indeed, the huge number of Russian casualties listed by Butler includes millions killed by Stalin, not Hitler, as Norman Davies notes.

Butler’s book begins with a Foreword by Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., who reports with a straight face that “Roosevelt had no illusions about Stalin’s Russia.” Butler insists that the notorious Joseph Davies, one of FDR’s sycophantic ambassadors to Moscow during the war, “was neither an apologist for Stalin nor pro-Communist” and quotes with approval the description of Yalta offered by FDR’s interpreter, Charles Bohlen: “Stalin held all the cards and played them well. Eventually, we had to throw in our hand.”

However, as this correspondence between Roosevelt and Stalin makes clear, the West had folded to “Uncle Joe” long before Yalta; Roosevelt simply never attempted to put any pressure on Stalin at all and threw away the cards he did possess without attempting to get anything in return. Indeed, FDR was soft on communism long before Yalta, rushing to extend diplomatic recognition to Stalinist Russia in 1933. As Butler notes, “Roosevelt is determinedly friendly” in his correspondence with Stalin. FDR told Adm. William Leahy early in the war that “I do not think we need to worry about any possibility of Russian domination,” while, with respect to Lend-Lease, Roosevelt’s attitude was that “whatever Stalin wanted, Stalin would get.” Indeed, FDR’s goal throughout the war was the establishment of an international order dominated by what he termed “the Four Policemen”: the United States, Great Britain, China, and the Soviet Union. From the start, Roosevelt viewed Stalin as a partner, not an adversary or even a rival.

Their correspondence begins with a glowing description of Stalin as “an austere, rugged, determined figure” by Harry Hopkins, who was dispatched to Moscow in July 1941 to impress upon Stalin “the determination of the President . . . to extend all possible aid to the Soviet Union at the earliest possible time.” Overruling the Pentagon, Roosevelt insisted that the aid sent to Russia was unconditional and that no effort be made to seek information concerning Soviet armaments or military plans. On March 7, 1942, Roosevelt wrote to all U.S. war agencies, informing them that he “wished all material promised to the Soviet Union . . . to be released for shipping . . . at the earliest possible date regardless of the effect of these shipments on any other part of the war program.” Roosevelt never wavered from this policy, and Butler presents numerous examples of Roosevelt castigating subordinates for being too slow in responding to Stalin’s demands or for thinking that maybe the United States should get something in return for all the aid being showered on Stalin. FDR had no problem seeing things from the Russian point of view, telling an administrator in charge of sending materiel to the Soviets that, “Frankly, if I were a Russian I would feel that I had been given the run-around in the United States.”

Throughout the war, Roosevelt was supremely confident in his ability to influence Stalin and determined to demonstrate to Uncle Joe how trustworthy he was. Roosevelt told Churchill that “I think I can personally handle Stalin better than either your Foreign Office or my State Department”; in April 1942, the U.S. ambassador passed along to Stalin Roosevelt’s belief that “if the two of you could sit down together and talk over matters there would never be any lack of understanding between our countries.” Roosevelt felt the key to his “success” with Stalin was his own trustworthiness: “The only reason we stand so well with the Russians is that up to date we have kept our promises.” Unfortunately for the peoples of Eastern Europe, the policy of exchanging good American promises for worthless Soviet ones ultimately encouraged the “Russian domination” that FDR professed not to worry about.

The moral stain inherent in the alliance with Stalin becomes most clear when considered in light of Poland, the supposed beneficiary of Britain’s declaration of war in 1939. As early as the Casablanca conference in January 1943, FDR was throwing away a bargaining chip that might have been used to preserve Poland’s independence by announcing that the war would end only with the unconditional surrender of the Axis Powers. Roosevelt got nothing in return for his attempt to alleviate Stalin’s paranoia. Indeed, even after the Allies had pledged themselves to a policy of unconditional surrender, Stalin repeatedly expressed concern that the Americans and British were negotiating a separate peace with Germany.

The betrayal of Poland began in earnest in April 1943, when the Soviets broke diplomatic relations with the Polish government in exile in London because the Poles had called for an investigation of the murder of thousands of captured Polish officers in the Katyn Forest. Stalin wrote to Roosevelt that this was “absolutely abnormal and contrary to all rules and standards governing relations between allied countries” and “a vile fascist slander.” FDR reassured Stalin that the call for an investigation of Katyn was a “stupid mistake” and that “Churchill will find ways . . . of getting the Polish Government . . . to act with more common sense.” (Of course, we now know what the Poles merely suspected in 1943: The thousands butchered at Katyn were killed by the Soviets, not the Nazis.)

The plot thickened at the Tehran Conference, where Roosevelt and Churchill essentially agreed to allow Stalin to keep the eastern part of Poland he had seized in 1939, without bothering to inform the Poles of this secret arrangement. Churchill told the New York Times that Tehran marked a “melding of minds, a union of spirit.” Who needed the Poles, when you had Uncle Joe in your corner?

After Tehran, the Poles could not expect even lip service from Roosevelt or Churchill. In March 1944, Churchill threatened to tell Parliament that, in view of the disagreements between Stalin and the Polish government, all questions of territorial change must await a postwar armistice; until then, Britain could recognize no forcible transfer of territory. Stalin responded by threatening that “if you make such a speech I shall consider that you have committed an act of injustice and unfriendliness toward the Soviet Union.” Churchill meekly deleted the offending portions of his speech; after Yalta, he actually defended just such a forcible transfer of territory in Parliament, telling the House of Commons that “I know of no government which stands to its obligations . . . more solidly than the Russian Soviet government.”

Those who view Churchill as an unblemished hero should carefully consider those words, spoken by the prime minister not only in the knowledge that he was lying but knowing that his brave words of defiance to the Nazis in 1939 and 1940 had been paid for, in part, with Polish blood, both in resistance to the Nazi invasion in 1939 and in the defense of Great Britain. In the crucial days of September and October 1940, Polish pilots constituted between an eighth and a quarter of the pilots available to Fighter Command for the defense of London and accounted for 18 percent of German planes destroyed on September 11, 14 percent on September 15, 25 percent on September 19, and 48 percent of all German planes destroyed on September 26. As Air Chief Marshall Dow-ding admitted after the Battle of Britain, “had it not been for the magnificent material contributed by the Polish squadrons and their unsurpassed gallantry I hesitate to say that the outcome of the battle would have been the same.” For this “unsurpassed gallantry,” the Poles received at Yalta what the Czechs had received at Munich—the subjugation of their country—with one difference: This time, Churchill defended the betrayal in Parliament.

Unlike Churchill, Roosevelt did not utter even occasional expressions of sympathy for the Poles. In February 1944, he cabled Stalin: “I fully appreciate your desire to deal only with a Polish Government in which you can repose confidence and which can be counted on to establish friendly relations with the Soviet Union.” Later that year, Roosevelt undermined the Polish government in London by telling Stalin that he was hoping for “the formation of an interim legal and truly representative Polish Government.” So much for the legal and representative Polish government that already existed. In December 1944, FDR begged Stalin, as a face-saving gesture, to delay recognizing the puppet government he had created in Poland until Yalta:

There was no suggestion in my request that you curtail your practical relations with the Lublin Committee nor any thought that you should deal with or accept the London Government in its present composition . . . I cannot, from a military angle, see any great objection to a delay of a month.

When Stalin rebuffed Roosevelt and told him that the presidium of the Supreme Soviet (over which Stalin claimed to be powerless) had already recognized the Polish Communist government, Roosevelt was understanding, writing to Stalin on February 6, 1945, that “I am determined that there shall be no breach between ourselves and the Soviet Union” and that “I hope I do not have to assure you that the United States will never lend its support in any way to any provisional government in Poland that would be inimical to your interests.” Thus did a war that began to preserve Poland’s independence end up handing over to the communists Poland (including what had been the Polish portions of the Ukraine and Byelorussia), together with East Germany, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Rumania, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, and Albania.

Far from resisting this denouement, FDR facilitated it. Ignoring the advice of the military, setting greater importance on compliance with Soviet requests for aid than on “any other part of the war program,” he got nothing in return for the massive amounts of materiel sent to the Soviet Union. Roosevelt always envisioned the Soviet Union as a partner in the postwar world, and he never sought to put the slightest pressure on Stalin to alter the Soviets’ rather different postwar plan of domination in Eastern Europe. Roosevelt’s actions toward the Soviet Union were in fact indefensible, as this collection of his correspondence with Stalin makes clear.

[My Dear Mr. Stalin: The Complete Correspondence of Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph V. Stalin, by Susan Butler (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press) 384 pp., $35.00]

Leave a Reply