“Republics exist only on tenure of being agitated.”

—Wendell Phillips

As a gorgeous American call girl lies murdered on the 46th floor of Los Angeles’ Nakamoto Tower—a Japanese conglomerate’s newly erected American headquarters—a grand opening celebration with Washington and Hollywood notables is in full-swing on the floor below. Security cameras have recorded the murder, but the video tapes have been tampered with by Japanese officials who are hindering the police investigation with cries of racism and “Japan bashing.” “Young Peter Smith—the LAPD’s Japanese liaison who knows nothing about Japanese behavior but who likes the exorbitant stipend Japan provides for “language training”—has been called to the scene. He is accompanied by semiretired policeman John Connor, who is steeped in Japanese culture from years of living abroad. While in Nakamoto’s glass elevator—for which the Japanese company received a special city permit to exceed the legal limit of ninety floors and to “bypass [American] unions because of a so-called technical problem that only Japanese workers could handle”—they overhear a group discuss the rate at which the Japanese are buying California real estate. “In no other country in the world,” laments Connor upon exiting the elevator, “would you hear people calmly discussing the fact that their cities and states were sold to foreigners.” “Discussing?” Smith retorts, “They’re the ones doing the selling.”

And so begins the latest thriller from novelist and film director Michael Crichton. The narrative is riveting and captivates the reader with high-stakes intrigue and political and industrial espionage. It is also, admittedly, fiction as political polemic, with situations and characters that exist exclusively as opportunities for cultural comment and political harangues. As Mr. Crichton states forthrightly in a postscript, “This novel questions the conventional premise that direct foreign investment in American high technology is by definition good, and therefore should not be allowed to continue without restraint or limitation.” There follows a bibliography more akin to an academic book on Japanese culture, economics, and business psychology than a successful work of mass-market fiction. He encourages his readers to delve deeper into actual trade practices and by so doing to learn a lesson in realpolitik: “It is absurd to blame Japan for successful behavior, or to suggest that they slow down. The Japanese consider such American reactions childish whining, and they are right. It is more appropriate for the United States to wake up, to see Japan clearly, and to act realistically.”

Rising Sun is replete with explanations of price fixing, product dumping, patent flooding, and influence peddling, and as such constitutes a virtual textbook on current Japanese trade practices. The author embellishes and enhances the credibility of his narrative with references to actual persons and recent events, such as the Toshiba controversy of 1987—when hordes of paid American lobbyists blanketed Capitol Hill to defend the company’s sale of critical submarine parts to the Soviet Union—and many of the instances of influence peddling recounted in Pat Choates’ 1990 Agents of Influence. If Mr. Crichton were rewriting his book today, he would no doubt add some mention of the latest scandal involving Japanese trade: on April 1 Japan’s largest military electronics manufacturer, Japanese Aviation, pleaded guilty in U.S. Federal Court to selling illegally to Iran navigation equipment for fighter jets. Japanese Aviation had been contracted by Honeywell, a deal the State Department approved, to make the parts only for Japan’s fleet of F-4 fighters. The Japanese company agreed to pay a $10-million criminal fee, $5 million to the State Department for administrative costs, and to accept a one-year ban on receiving any additional export licenses from the United States. The penalties are the highest ever imposed for export violations.

But the most interesting and no doubt controversial sections of Rising Sun are the explanations of the cultural differences between Japan and the United States and the alarming examples of the extent to which Japan has penetrated America’s cultural infrastructure. On Japanese racism:

The Japanese think everybody who is not Japanese is a barbarian. They mean it, literally: barbarian. Stinking, vulgar, stupid barbarian. They’re polite about it, because they know you can’t help the misfortune of not being born Japanese. But they still think it.

On the differences between Japanese and British and Dutch investment in the United States:

Yes, it’s true that the British and the Dutch both have larger investments in America than the Japanese. But we can’t ignore the reality of targeted, adversarial trade as practiced by Japan— where business and government make a planned attack on some segment of the American economy. The British and Dutch don’t operate that way. . . . And, of course, if we want to buy a Dutch or English company, we can. But we can’t buy a Japanese company.

On the free trader’s retort that the balance of payments with Japan is dropping:

Of course it only looks better because they don’t export so many cars to us now. They make them here. . . . They’ve stepped up purchases of oranges and timber, to make things look better. Basically, they treat us as an underdeveloped country. They import our raw materials. But they don’t buy finished goods.

On Japan’s penetration of American education:

Japanese companies now endow twenty-five professorships at M.I.T., far more than any other nation. . . . At the University of California at Irvine, there’s two floors of a research building that you can’t get into unless you have a Japanese passport. They’re doing research for Hitachi there. An American university closed to Americans. . . . You know they already own ten American colleges. Own them outright. . . . So [in case of a backlash against Japan] they can be assured of the ability to send young Japanese to America.

“The Japanese are not our saviors,” concludes Mr. Crichton in his afterword. “They are our competitors. We should not forget it.”

Trade and competition between America and Japan was the subject of the 1989 Japanese best-seller The Japan That Can Say No: Why Japan Will Be First Among Equals. The book was a series of speeches given by Sony chairman Akio Morita and by novelist and longtime Liberal Democratic Party leader Shintaro Ishihara. They frankly criticized America for meddling in Japanese affairs, encouraged Japan to reassert its will in Pacific affairs by using its vast wealth and technological know-how, and urged the country’s leadership to quit playing “little sister” to a patronizing and enfeebled Uncle Sam. The Pentagon caught wind of the book and arranged for a bootleg version of it to be circulated in Congress, after which a fury of anger swept over Capitol Hill. Ishihara contended that the outrage was the result of the Pentagon’s shoddy translation, where upon he negotiated for an English-language volume of his portion of the book—Akio Morita having dissociated himself from the project because of the controversy—along with some additional chapters to be published by Simon and Schuster. The book appeared in January 1991, and was widely reviewed by the American media. But much has happened since that time to make a reappraisal of Ishihara’s views both prudent and productive, not least our of which is the wider dissemination of his ideas with the recent release of a paperback version of his book.

At one point in Rising Sun, fictional Senator John Morton says, “You know, some day an American politician is going to do what he thinks is right, instead of what the polls tell him. And it’s going to look revolutionary.” To the annoyance of the ruling elite in Washington and Tokyo, both nations now have such “revolutionary” figures, and they represent not further politics as usual but a desire for fundamentally changing the course of their respective countries. They are Patrick Buchanan and Shintaro Ishihara.

The similarities between the two men are striking. Both are strong and pugnacious characters—Buchanan the young boxer brawling with a cop, Ishihara the brass kid of occupied Japan provoking U.S. soldiers with his refusal to step aside in deference to allow “the new conquerors” to pass. Both men abhor the politically fashionable and opt instead for frank and free discussion, and both as a consequence have been denounced as reactionary, racist, and ultranationalist (these being the kindest and gentlest of the epithets hurled at Pat Buchanan). And both men have challenged their country’s ruling political class by calling for a new nationalism and a return to a foreign and domestic policy explicitly based on national prosperity, security, and self-interest. One might think that the statement, “Without nationalism—a strong sense of roots and identity—there cannot be internationalism, only a shallow cosmopolitanism,” came from Pat Buchanan or a Chronicles editor, but it is classic Ishihara. Whether it be Buchanan’s America First or Ishihara’s Japan First, both policy platforms stem from fervent patriots proud of their own cultural and national heritage.

This is not to deny the many trade and foreign policy issues over which both men as heads of government would doubtless disagree. Indeed, Washington would do well to consider how U.S.-Japanese relations would change if Tokyo ever again translated the Japan First policy it pursues in the economic realm into the field of foreign policy and military strategy. And Tokyo would likewise be wise to contemplate how relations will be altered when a regime truly representative of American interests does finally recapture the White House.

A second recent factor that should cause a reappraisal of Ishihara’s work is the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and how this will affect what he—in the most controversial portion of his book—called Japan’s ability to play the “technology card.” He reminds his American readers that Japan is not only now strong enough technologically and financially to take its place as a world military power, but that America’s entire nuclear arsenal now depends on Japanese microchips.

A deal with the Soviet Union over semiconductors cannot be completely ruled out. As I have noted, microchips determine the accuracy of weapons systems and are the key to military power. U.S. strategists count on Japan’s ability to mass produce quality chips. Yet some Japanese businessmen believe that if Moscow returns the Northern Territories, we should terminate the security treaty and become neutral. They hope Japan would then receive exclusive rights to develop Siberia.

Ishihara, in fact, boldly calls the next century the Age of the Pacific, and does not rule out a new kind of Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere governed by Tokyo and extending as far as the economically needy countries of Eastern Europe. Though he admits that “playing the leading man” in world affairs has lately been “out of character” for Japan, he reminds his countrymen that “stage fright will keep us in the wings forever.” After all, he concludes—and Washington take heed—Japan’s “long history and rich culture have prepared us for the limelight.”

At another point in Rising Sun, Senator John Morton lambastes free traders who contend that it does not matter where companies are located or where products are made, whether America is a producer of potato chips or computer chips, and who see national economies as “old fashioned and out of date. To these people, I say—Japan doesn’t think so. Germany doesn’t think so. The most successful countries in the world today maintain strong national policies. . . . They nourish their industries, protect them against unfair competition from abroad. . . . But if we continue as we are, mouthing the ancient platitudes of a free market economy, disaster awaits us.” Senator Morton, of course, is a fictional character, but his ideas are alive and well in the latest book by the Educational Foundation of the U.S. Business and Industrial Council.

America Asleep is destined to become the economic manifesto of the America First movement, and a more thorough discussion of free trade and protectionism and of their historical antecedents in American politics is nowhere to be found. The book is a series of ten essays by leftists, rightists, journalists, and economists, and it is edited by USBIC President John Cregan and has a foreword by Pat Buchanan. The essays are factual and polemically powerful and will doubtless leave all readers—friend and foe alike—convinced of the new nationalists’ commitment and resolve. It is indeed, as Pat Buchanan concedes in his foreword, “the international hour of President Bush. But he is leaning against a nationalist wind that will soon reach gale force.”

Economist William Hawkins has an informative essay on the historical roots of free-trade ideology. He convincingly argues two points: first, that nations throughout history that have relied exclusively on trade and not on the strength of their own productive capabilities built their national castles on volatile sand—such as 17th-century Spain that fell to the Dutch, and the 18th-century Dutch who fell prey to the mercantilist policies of England; and secondly, that free-trade ideology evolved from classical liberalism of the 19th century that separated economics from politics, power from wealth, and viewed not national interests but only “citizens of the world.” He argues that this historical perspective is important because, as historian Charles Wilson has noted, the current tendency overseas is “to revert to conditions which in some ways resemble those of the seventeenth century rather than those of the nineteenth.”

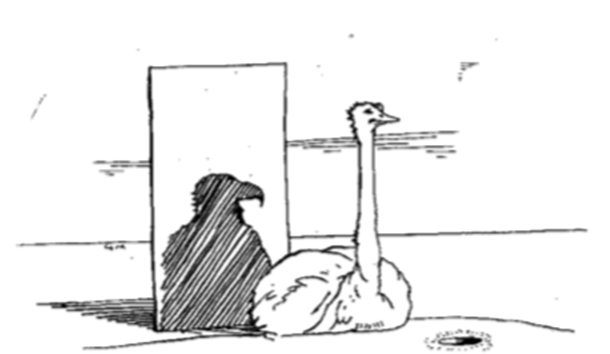

This refusal to acknowledge the openly mercantilist policies of our trading partners abroad is what John Cregan in his introductory essay terms “ostrich economics”—”an excuse to keep our collective heads buried in the comforting sands of theory.” Longtime Republican Party organizer Helen Delich Bentley echoes Mr. Cregan and shows in her essay how such theory is tied to the “Gospel According to [Adam] Smith.” Former International Trade Commission member Alfred Eckes complements Mr. Hawkins’ analysis of free trade with an essay on “Reviving the Old Paradigm,” delineating the historical roots and champions of American protectionism from Henry Clay and his “American System” to Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, and, ironically enough. President Bush’s own father, Connecticut Senator Prescott Bush.

Chronicles contributing editor and Washington Times syndicated columnist Samuel Francis traces the ways in which free-trade dogma fits into the larger cultural picture of globalism, transnationalism, and open-border ideology that threaten American sovereignty and national security. The irony, he writes, is that “at the very moment when the Soviet Union . . . is in a condition of collapse, the United States itself is encountering a profound challenge to its very existence as a sovereign and independent nationstate. . . . ” This threat to American sovereignty and national security is also taken up by Kevin Kearns, a fellow at the Economic Strategy Institute and a former director of the State Department’s Office of Defense Trade Policy, and by Edward Walsh, senior editor of Sea Power and a former research director for the USBIC. Mr. Kearns “discusses the “un-holy alliance” of neoclassical economists, free-trade ideologues, and lobbyists for foreign interests that thwarts any attempt to check the further deterioration of America’s high-tech industrial base, while Mr. Walsh highlights what he calls our “technology drain,” our diminishing share of the world market in such crucial areas as robotics, microlithography, and electronic semiconductors (which the Defense Department has classified as essential to 13 of its 20 most critical technologies).

Businessman Boone Pickens, as the largest shareholder in Koito, a member of Toyota’s keiretsu family, provides an enlightening firsthand account of Japanese cartels. These economic megapyramids known as keiretsus are illegal in the United States as they violate our antitrust laws. But as a character in Rising Sun describes them, to get a feel for what keiretsus are like “imagine an association of IBM and Citibank and Ford and Exxon, all having secret agreements among themselves to cooperate, and to share financing and research.” Mr. Pickens recounts how the Japanese have tried to keep him off the corporate board; how he must contribute to the fees that Koito pays to American lobbyists who are working in Washington to keep him off the board; how they refuse to show him the corporate tax records; how Toyota sells the Lexus at below cost in America in an attempt not to win profits but to gain market share, and how Japan can afford to do this in numerous industries because of the financial security that keiretsus provide. The price of the Lexus may be low now, he warns, but “when enough market share has been acquired, that price is going to go up. And GM, Ford and Chrysler are losing market share so quickly that it is scary.”

In These Times and New Republic editor John Judis, and former president of the USBIC, Anthony Harrigan, discuss the politics of the current debate over national economic strategies. As Mr. Judis discovered while researching his landmark 1989 expose on Japanese lobbying, the exact composition of the “Japan lobby” is difficult to categorize because it creates some strange economic and political bedfellows. He nonetheless clearly separates the various factions, and traces as well how World War II and the Cold War caused fissures over free trade on both the left and the right. Anthony Harrigan concentrates on the revolving-door network between U.S. government officials and the foreign lobbyist community and highlights many of the Beltway’s “conservative” think tanks:

Conservative and libertarian think tanks such as the Heritage Foundation and the Cato Institute continue to grind out statements that insist that everything is wonderful. Many of the conservative think tanks, to be sure, are recipients of massive financial grants from Japanese, Korean, Taiwanese and European interests. Many conservative think tanks now have a tremendous vested interest in defending foreign commercial entities.

The “old national interest American public philosophy,” concludes Mr. Harrigan, “has been abandoned by these self-styled conservatives.”

* * *

In Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal the squire Jons says to his master, “For ten years we sat in the Holy Land and let the snakes bite us, insects prick us, wild animals rip us, heathens slaughter us . . . fevers consume us, all to the glory of God. . . . Our crusade was so stupid that only an intellectual could have invented it.” What an apt description of America’s current economic plight. In plain face of our lost industrial base, mounting foreign debt, and increasing vulnerability to technological blackmail, only Ivory Tower pundits entirely removed from reality or politicians and think-tank lackeys on the take from foreign nationals could be indifferent to the parasitical trade practices debilitating our body politic for the greater glory’ of the Free Trade God. Richard Nixon recently chastised America for not giving Russia sufficient foreign aid in its time of social and economic need, warning that fifty years hence we may well be debating “Who lost Russia?” as we debated “Who lost China?” in the 1950’s. But with free trade, multiculturalism, transnationalism, and unlimited immigration reigning supreme, it is doubtful whether America will have the luxury in the next century of debating Russia’s socioeconomic state. The pressing question of the day will be who lost Detroit, Miami, Los Angeles, and that erstwhile republic known as the United States of America.

[Rising Sun, by Michael Crichton (New York: Alfred A. Knopf) 355 pp., $22.00]

[The Japan That Can Say No: Why Japan Will Be First Among Equals, by Shintaro Ishihara (New York: Simon and Schuster) 158 pp., $10.00]

[America Asleep: The Free Trade Syndrome and the Global Economic Challenge, Edited by John P. Cregan, Foreword by Patrick Buchanan (Washington, D.C.: The United States Industrial Council Educational Foundation) 201 pp., $8.95]

Leave a Reply