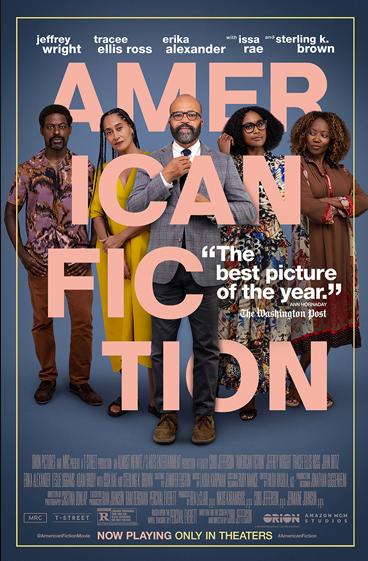

American Fiction

Directed and written by Cord Jefferson ◆ Produced by 3 Arts Entertainment, MRC Film, Percival Everett, et al. ◆ Distributed by Amazon MGM

Tyranny cannot withstand ridicule. Our minders in the woke administrative-managerial caste know that all too well and, keenly aware of the power of culture, try hard to suppress mockery of their status quo. Just ask Star Wars actress Gina Carano, who was fired by Disney in 2021 for making fun of transgender ideology on her personal Twitter account.

Wokesters are notoriously sour on humor, which requires more abstraction, critical thought, and levity than they cope with or tolerate in others. But, occasionally, a sprout of satire can penetrate the thick permafrost they have imposed on our cultural landscape. Cord Jefferson’s American Fiction is a fine new addition to that genre.

The film’s origins go back more than 20 years, to the black writer Percival Everett’s novel Erasure, which features an upper-middle class black writer, Thelonius “Monk” Ellison, as the protagonist. Monk’s books are judged “not black enough” for the sensibilities of the progressive and almost uniformly white literary establishment. At a crucial inflection point, his agent tells him that they compare poorly to a new book by a younger black writer, agonizingly titled We’s Lives in Da Ghetto, whose indulgence in crude racial stereotypes and clichéd tropes of underclass black life wins gratuitous plaudits from white tastemakers for its supposed “authenticity.”

Thoroughly frustrated, Monk abandons his style, which is steeped in the tradition of the Western literary canon, to write a book satirizing the younger writer’s work. First titled My Pafology and later simply F***, the novel within Everett’s novel abounds with crime, drugs, vulgarity, and sexual license, all told in exaggerated black slang and peppered with phonetic misspellings. Despite Monk’s satirical intent, his novel proves a smashing success and wins a huge advance, enormous popular sales, a lucrative movie deal, and a major literary award. Trapped in his own charade, Monk is forced to abandon his urbane persona and act like the “authentic” black man—an unstable, urban criminal outcast—that the shallow white literary world expects him to be.

Erasure, which was published in 2001 by the now-defunct University Press of New England, is the product of a different and, in retrospect, simpler era. It predated not only George Floyd and the convulsive racial reckoning that resulted from his killing, but also the hopes and disappointments that swirled around Barack Obama, the progressive takeover of most of our institutions, the mainstreaming of cancel culture, and the pervasive intrusion of identity politics throughout national life under the Marxist-infused banner of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Race was a touchy issue at the turn of the century, but the radical, consequence-laden racialism commonplace today was then situated decidedly on the lunatic fringe of society and in the remote recesses of the Ivory Tower. It is a testament to how far we have descended that Erasure should now find its way to adaptation for the silver screen.

There is no doubt that black identity lies at the heart of both novel and film. Monk shares his surname with the black writer Ralph Ellison, whose award-winning 1952 novel Invisible Man meditated on black identity from the perspective of an educated and highly articulate protagonist very much like Monk. His given name and nickname obviously refer to the iconic black jazz musician Thelonius Monk, whose distinctively improvisational musical style complements Monk’s literary improvisations. A subplot embellished in the film centers around Monk’s relationship with his elderly mother, an Alzheimer’s patient whose condition causes her to lose not only her memory but, tellingly, her sense of self. By the end of the novel, Monk, too, begins to show signs of the same illness as he accepts his award.

With Everett’s approval, Jefferson adapted the novel to hit harder in the current climate. The Monk of American Fiction is not merely a frustrated writer, but also a college English professor. He becomes a cancel culture victim when he writes the forbidden “N-word” on his classroom blackboard while trying to lead a discussion of Flannery O’Connor’s short story “The Artificial Nigger”—itself a portent of Monk’s imposture—outraging an annoying white girl named Brittany, who flees the room in tears. Punished with a mandatory leave imposed by his jealous and less-gifted colleagues, and motivated by a disappointing family visit to his mother, as well as the rejection of his latest manuscript, Monk bangs out his satirical book.

In the buildup to the literary award the book ultimately wins, the selection committee unwittingly asks Monk to join it as part of a “diversity push.” Alongside white liberal writers who claim to find his book fresh without realizing he’s the author, he gets closer to his younger rival, a fellow black committee member who secretly shares his cynicism and admits that she tailors her work for guilty white liberals regardless of any negative stereotypes it might perpetuate. On the other hand, Monk’s romance with a neighbor of his mother, a liberal public defender of color, sours when her unmitigated race consciousness causes her to praise the satirical book without discerning either his authorship or intent.

In addition to the emotional awakening from these situations, the film gives Monk a gay brother whose flamboyant lifestyle challenges notions of acceptance across social categories, and a beloved family maid who finds love late in life and suggests Monk overcome his various hangups.

In the end, Monk does not begin to share his mother’s decline, but rather reveals that the plot up until the literary award ceremony was really a screenplay for a film telling his actual story. The film producer pressures him to write a violent ending, in which the police storm the ceremony and gun down Monk as he, in his criminal persona, is about to accept the award. Monk and the producer drive away from that violent scene’s filming as Monk makes eye contact with a black actor playing a slave in a separate film in production nearby.

Jeffrey Wright, a lawyer’s son who attended Washington, D.C.’s elite St. Albans School and Amherst College, is an accomplished film and television actor who perfectly captures Monk’s existential angst. The character must balance education and refinement with the absurdity of his circumstances and the insecurities of his racial identity. Wright delivers arrestingly in that role.

Most of the other characters are stereotypes, however, and cringeworthy to varying degrees. This keeps within the ethos of the film, but Jefferson’s expansion of Monk’s family and romantic life introduces inevitable longueurs that distract from the plot and never quite succeed in adding nuance to its message. By far, the film’s tightest and funniest scene is its first few minutes, which detail Monk’s defenestration from his teaching post. What follows seems almost like a prolonged afterthought with unnecessary sentimentality mixed in.

Nevertheless, Jefferson deserves great credit for taking on the new racialism in a medium almost totally dominated by a progressive left, a left that propagates its divisive ideology and suppresses any alternate or contradictory viewpoint.

Perhaps inevitably, media bias affected American Fiction’s distribution and reception. Although the film won numerous prerelease festival prizes last fall, its distributor, Amazon MGM, chose to delay its already limited commercial release until Dec. 15, with an “expansion” coming just three days before Christmas and dispatch to paid streaming shortly thereafter. Many major publications did not review it or reviewed it tepidly or negatively. The New York Times dismissed the film’s satire as a “gimmick.”

Unsurprisingly, American Fiction only grossed about $23 million in cinemas, compared to $1.5 billion for Greta Gerwig’s atrocious Barbie, an unabashedly anti-male film about dolls. Only after American Fiction was nominated for five Academy Awards—including Best Picture and Best Actor (it won the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay)—was it released in a larger number of cinemas. Nevertheless, it did encouragingly well among with black film organizations, sweeping almost every category in competitions held by the Black Film Critics Circle, the African-American Film Critics Association, and the Black Reel Awards. This could be a good sign that the politics of race are finally coming to a natural and badly needed end.

Leave a Reply