In the world of blue bloods and blue books, where nicknames like “Oatsie,” “Tootsie,” “Bunny,” and “Babe” abound, being called “Sister” isn’t particularly unusual. Even in her professional life. Sister Parish never used her given name, Dorothy May, though regarding her nickname she once commented,

It has not been an easy cross to bear. My husband constantly complained about the awkwardness of being married to a woman whom he called Sister. People who don’t know me lower their eyes in embarrassment when the Lord’s name is taken in vain in my presence. I often receive calls from religious groups asking me if I’d meet refugees at the dock. And when I was asked to help “do” the White House, a newspaper headline announced “Kennedys Pick Nun to Decorate White House.”

Being a descendant of Cotton Mather and Oliver Wolcott and the granddaughter of Edith Wharton’s physician had much to do with Sister’s later success, but her lineage proved no protection against unpromising personal beginnings. A plain baby and poor student. Sister seemed destined for failure on all fronts. In first grade, she learned that “George Washington is Jesus’ father.” Her record did not improve thereafter. She spent a single year at Foxcroft, the tony finishing school in the horse country of Middleburg, Virginia, before ending her formal education without even a high-school diploma. Sister spent most of her time at Foxcroft in the infirmary, where it was “more comfortable” (she had learned how to induce nosebleeds by pushing a tender spot on her nose). About her withdrawal from Foxcroft, she says:

At some point, the school became so alarmed at my utter lack of progress that they took a step unheard of in those days. They suggested that I be analyzed by a doctor. Mother took me to Dr. Draper. He was a psychiatrist, but he also was a relative, so that made it all right. He asked me, “Do you like school?” and Mother answered, “No.” He asked, “Do you like riding?” and Mother answered, ‘Yes.” He asked, “Do you believe in God?” and Mother answered, “No.” Finally, he told me that I could leave. He asked Mother to stay.

Nothing was left untried in Sister’s upbringing, but all efforts at instruction proved futile. During trips to Europe, Sister kept her eyes “closed tight in every cathedral.” Not until she was 18 and revisiting her family’s apartment in Paris did Sister feel the first stir of interest:

I marveled at the delicately carved Louis XV and XVI fauteuils covered in exquisite stripes and damasks. I began to feel the love of painted furniture that has followed me through all my decorating. I knew I was discovering something important, but I didn’t know why. The rest of the trip was spent touring French houses. This time, my eyes were open, and so was my heart. I was at last beginning to understand beauty and the role it would play in my life.

This ineffable feeling, together with her sense of tradition and family, was the rest of Sister’s artistic sensibilities:

Already, at eighteen, I had a deep, abiding belief in all things inherited, and all things of real lasting quality. I was not afraid of change, but I firmly believed in the continuity of values that I had learned while growing up. A sense of family and of home were the strongest values of all.

In Sister’s family, pedigree was not just an exclusive club, but a sustaining “wire of character” that linked present to past generations.

Although not rebellious by nature, Sister, as a young newlywed, delighted in shocking her mother-in-law by painting a gift of ebony furniture white and having curtains made from mattress ticking. This was just the beginning of the shock waves Sister was to cause. When the stock market crashed and it looked as though the young Parishes would have to accustom themselves to a more modest lifestyle. Sister, who had been informally helping neighbors with decorating, took matters into her own hands and hung out a shingle. It took Harry three turns through Far Hills, New Jersey, before he noticed the small sign that read “Mrs. Henry Parish II Interiors.” One of her very first jobs was helping a new restaurateur, Howard Johnson. She used aqua walls, aqua place mats, aqua uniforms. She did the job for “free ice cream” and “never used aqua again.” Although Harry was a steadfast supporter of his wife’s work and a beneficiary of her success, this step did not come without a price. An anticipated inheritance from Harry’s uncle was forfeited because Sister had gone “into trade.”

Sister Parish was born into the social elite, and she did stick close to her own kind, with some exceptions. In addition to many of the young staff at Parish-Hadley, Sister felt close to her black driver and the permanent residents of her beloved summer retreat at Dark Harbor, Maine. She was intrigued by celebrities and was the first to pay social visits when actors came to Dark Harbor, and she invited Andy Warhol to parties in New York. (At these gatherings, Warhol would remain closeted in one of Mrs. Parish’s lavish bathrooms or observe the party mutely from a corner. Eventually, the invitations to Warhol stopped, Sister pronouncing him “no fun.”)

Sister was quintessentially American, a pioneer who introduced informal, unpretentious craft materials into traditionally formal and highly sophisticated settings. Along with her partner, Albert Hadley, Sister invented the “American Country Style.” In 1990, she wrote,

Years ago, mv partner, Albert Hadley, and I were delighted when patchwork quilts, four-poster beds, painted floors, knitted throws, rag rugs and hand woven bedsteads were first listed among the “innovations” of our firm. The list sounds old-fashioned, and no decorator wants to be that, but Albert and I understood that innovation is often the ability to reach into the past and bring back what is good, what is beautiful, what is lasting.

This biography is like one of Sister’s lovely old patchwork quilts—or collages. Sister’s daughter and granddaughter have assembled recollections from an array of family, friends, clients, and business associates—decorators, domestic staff, craftsmen and women. These different voices combine to effect a delightful portrait of the grande dame of decorating, a crusty dowager with razor wit who makes Martha Stewart look like a Madison Avenue mock-up, a kind of talking billboard. The best parts of Sister, are, of course, those passages written by Sister herself. (She had tried to write an autobiography, and I assume these long passages are taken from those manuscripts.) Eloquent and witty, her stories end with just the right punch. Sister was the embodiment of wit and drama. She spoke in perfect hyperbole: “You can’t paint it green—it would be fatal.” But then, extreme language may have been necessary for the task at hand—”making the rich look right,” as a Women’s Wear Daily article put it. Her success may have come as much from knowledge of her clients as from her skills as a decorator. Sometimes Sister would take a client shopping and ask her to pick out the one piece in a shop she would most like to have. Usually, when the client selected an object, a tag underneath would say, “Hold for Mrs. Parish.”

Sister Parish died in Dark Harbor in 1994 at age 84. In her final years, she had written, “The fog is closing in around me. I feel very alone. But I also feel content for the sense of continuity is still strong within me.” Sister had requested that “America the Beautiful” be played at her funeral; she was laid to rest between her two Harrys, husband and son. Sister Parish worked for the rich, but her contribution to interior decorating and good taste has benefited craftsmen nationwide, and homes throughout the country.

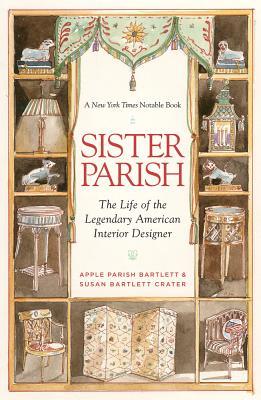

[Sister: The Life of Legendary American Interior Decorator Mrs. Henry Parish II, by Apple Parish Bartlett and Susan Bartlett Crater (New York: St. Martins Press) 357 pp., $35.00]

Leave a Reply