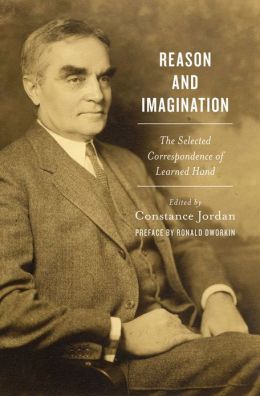

This selection from around 65,000 pieces of correspondence, edited by Learned Hand’s granddaughter, a professor emerita of English at the Claremont Graduate School, could not have been better done. Both Hand’s letters and the letters of his correspondents are included; some of the most notable exchanges are with Bernard Berenson, Philip Littell, Walter Lippmann, and Felix Frankfurter.

Hand’s opinions, standards, and career are a reproach to the judges of our time. Only twice in nearly half a century did he declare a statute unconstitutional: in the Schechter case, under duress of superior authority; and in Baldwin v. Seelig, involving a clear discrimination against out-of-state producers. He viewed the Due Process clauses of the federal Constitution in their substantive aspects with abhorrence and at one point proposed five different ways of repealing them. “They contradict the very presupposition of a democratic state.” For him, legislatures were the supreme organs to reconcile social differences. They might make mistakes, but these were subject to swift self-correction. Not so the judgments of courts. “[L]awsuits, however large the jury, cannot be in the end a substitute for personal confidence in leaders.” Nonetheless, “an enforced pause in revolutionary changes may be a condition upon the very continuance of democratic societies.” If a chamber of revision to provide second thoughts was needed, it should be legislative in character. The delaying powers of the British House of Lords after 1911 made sense to him; it would have greater legitimacy if members were appointed for life rather than by inheritance, a development that has since occurred. America’s accidental substitute for this was the Senate, whose rural bias checks transient majorities.

The role of courts in his view was that of the magistrates described by Aristotle in the third book of the Nicomachean Ethics: to restore the status quo (corrective justice) when litigants commit crimes and civil wrongs disruptive of society’s compromises. Change in these was for the ruler to effect: a monarch or dictator in authoritarian systems, a legislature in democratic ones. The judge’s job was to discover through “reason and imagination” how past legislators would address each new problem. This, Justice Scalia to the contrary notwithstanding, requires more than a dictionary, but the Framers’ values and intentions were not to be confused with those of the judge. Judges’

authority would disappear as soon as their decisions had no greater professed authority than the beliefs of the judges as to what was proper and just. Let them be on guard that they assume no more than an overwhelming consensus.

Hand scandalized both “liberals” and his frequent correspondent Justice Frankfurter by concluding that the only possible intention that would justify the school-segregation decision was a purpose to abolish all racial distinctions, and in the end doubted that the courts could legitimately find such a purpose.

These aspects of Hand’s position are well known, but not as well known as they should be. What lends this volume its interest is Hand’s remorseless intellectual candor and integrity, and his passing observations on the politics of his era, which suggest not only that Hand was a fine judge, but that he would have made a fine secretary of state as well.

Hand’s comments on the cavalcade of presidents communicate this. For him, William McKinley was a “pharisaical jellyfish,” (a description that some may think fits the present incumbent). Theodore Roosevelt, whom he supported, had “real breadth of vision, foresight . . . granting his violence and lying, his personal untruthfulness, he is today the best patriot we have.” As for William Howard Taft, he told Frankfurter, “you are a little hard on the old boy. Forgive his exaltation of his prerogative, and remember what constitutionalism did for the country during its first century.” Wilson provided

an example of personal government and reliance upon the executive alone which is much the worst of my time . . . he is not genuinely rational. Washington is now a place where you get no hearing unless you come from the proper crowd.

Hand continued,

Wilson has been increasingly for me the type of statesman which I most distrust and individually a most repellent human being, the American president for whom I have achieved the greatest personal dislike . . . his greatest failing, the gift of inspiring others, particularly women, with a sense of the loftiness of his moral principles. Men like Wilson are soothsayers, misleaders of the children of men.

As for Harding, he “seems to me to be impossible . . . an appeal to apathy, little Americanism and the tacit assumption that the old crowd of wirepullers playing in with the big interests is on the whole most to be trusted.” Hand began with high regard for Hoover: “I am for Hoover on any ticket, Soviet included.” However, “Hoover’s crabbed and somewhat churlish nature was a great defect.” But “I have perhaps an extreme leaning toward the tough-minded. Hoover, whatever his faults, seems to look rather that way.” In the depth of the Depression, Hand found Hoover “a timid soul,” though some of his actions—he probably had in mind the Hoover Moratorium, the nomination of Cardozo, and the signing of the Norris-La Guardia Act—“justify the hopes of those of us who continue to believe in him.” Later, during World War II, he was to allude to “that old cobra Hoover whose teeth are pretty well gone but who can still spit poison and does.”

Hand considered that FDR as war leader had “an ability to get the true balance of values and a courage to risk everything upon the cast.” However, “win or lose, our revered system of checks and balances is gone. The American people is getting used to the idea that when the wind blows, the Captain is the boss and what he says goes.” As for the New Dealers, “I rather like their ideas but their techniques do not please me.” The President had “a nonreflective feeling toward the ruling classes . . . [a] willingness to fan incendiary animosities.” Yet he “conquered a terrible [personal] calamity.”

I do not for an instant suppose that he could stand any competent cross-examination by a hostile economist on any of the issues. Maybe if we had a nation of patient cows, it would have been better to let things alone and feed the down and outers until things picked up.

Roosevelt “as I look back was not a really likeable person. I don’t believe I could possibly have loved him. I disbelieve in his generosity.”

Hand had no direct comment on Truman, though he credited Dean Acheson with bringing “a note of wisdom, competence and honesty into public affairs.” As for Eisenhower, “you must judge with the utmost lenity, his position is nearly impossible. He cannot rule as a coalition president—that won’t wash. He is not a clever man but he is something better than that—he is a just and selfless man.”

If one looks to the Democrats one sees a typical egalitarian party that will deny nothing to the ordinary voter, and will not hesitate to endanger the whole stability of the country by financial excess. If one looks to the Republicans, one sees as fantastic and outrageous an appeal to primitive passions as we have ever had there.

Hand’s views on foreign policy included a conviction that Stimson erred in trying to curb the Japanese in China. In Mexico in 1913 during the civil war there, he told Frankfurter, “I should help anyone who had a chance [to stop the fire] . . . [Y]our duties are to avoid entangling your country.” Versailles sought to “right every wrong that has been done for the last four hundred years and create more grievances than before.” Hand considered that Korea was a distraction from Europe that should be settled, and that further military involvement in Asia was unwise. He believed in a concert “in which Britain and Russia and ourselves would be recognized for what we are.” He understood that “People do not take sides so much because of their economic interests as because of some wounding of their self-esteem”—an observation with great pertinence to today’s Middle East.

Though acknowledging the need for ameliorative legislation, Hand believed that “a general presumption of laissez-faire is the proper basis of government.” He stated a conservative case for legislation like the minimum wage, which “gives us hope of meeting its cost by increased efficiency . . . A means of ascertaining who of the race is fit to survive without mingling the fit and unfit in a vague class half fed and half educated.” As for the evils of his time, which extended to aesthetics as well as politics, “if I were to lay my finger on the rotten spot, I would say it was the sense of nationality.” Americans were “a self-sufficient, aggressive people, who have never known and do not believe that this is a world of misery and terrors.”

On the antitrust laws, Learned Hand’s views are unfashionable today. He told Sen. Harley Kilgore, who asked his advice about legislation,

although the economic question is vital, it is not as important as the political one . . . [which is] the impact upon the social habits of those affected by the proposed combination. . . . [I]t is one thing to be independently engaged in business and another to be employed by others, to be employed in a small business is different from being employed in a very large one. The reflective appraisal of these and an eventual decision between them are of the very essence of legislation.

Congress made that appraisal shortly thereafter in enacting the Celler-Kefauver and bank-merger statutes, which the courts, applying economic criteria alone, have nullified.

Judges, Hand thought, “have got ourselves into the mess we are in here in America by failing to remember how strictly our duties should be interpretive.” An appellate judge’s work, in his opinion, “ought preeminently to be an interpretation of the more permanent relations of men,” while “Holmes’ background of acquaintance with letters and history kept him from the chief danger . . . the automatic self-affirmation of ideas because they fit into one’s own sub-conscious predispositions.”

There is hardly a line in these letters that does not stand as an indictment of today’s Supreme Court and today’s legal academy. Constance Jordan displays a very sharp eye in identifying issues of enduring significance; few lawyers, if any, could have done as well. Her notes are both sophisticated and unobtrusive. Professor Jordan is not responsible for the small typeface in which the book is set, yet its effect is to give readers larger helpings of caviar than they would normally receive from a book of this size.

[Reason and Imagination: The Selected Correspondence of Learned Hand, edited by Constance Jordan (New York: Oxford University Press) 480 pp., $39.95]

Leave a Reply