“Our Union rests upon public opinion, and can never be cemented by the blood of its citizens shed in civil war. If it cannot live in the affections of the people,

it must one day perish.”

—President James Buchanan, 1860

A poll of American historians, not long ago, chose James Buchanan as “the worst” American president. But judgments of “best” and “worst” in history are not eternal and indisputable truths. They are matters of perspective and values, even of aesthetics. They can change as the deep consequences of historical events continue to unfold and bring forth new understandings. These historians show their characteristic failure to pursue balance and their subservience to presentism and state-worship. They think Buchanan should have ordered a military suppression of the seceded Southern states during the last months of his term of office in 1861. Not only do they have no sympathy for a desire to avoid civil war, but they totally fail to understand the context. There was only a small army, most of the best officers of which sympathized with the South, and there were eight states that had not seceded but were averse to action against the Confederacy. More importantly, there was an immensely powerful and even predominant states’ rights tradition that had its followers in the North as well as in the South. For most Americans, even many who had voted for Lincoln, coercion of the people of a state was unthinkable until it became a fact.

These historians prefer Lincoln as our “greatest” president. He had less than two fifths of the popular vote, but he had an aggressive rent-seeking and office-seeking coalition behind him, and he did not hesitate to make war, though he egregiously miscalculated, expecting an easy victory. That there was much intelligent and respectable opposition to him in the North is perhaps the biggest untold story of American history. Ex-President Fillmore said that Lincoln’s election justified secession. Horatio Seymour, the governor of New York, asked pointedly why Lincoln was killing fellow Americans who, indeed, had always been exemplary citizens and patriots and ready to defend the North against foreign attack. A New York editor wanted to know exactly where Lincoln got the right to steal the possessions and burn the houses of Southern noncombatants. On July 4, 1863, while the battle raged at Gettysburg, Buchanan’s predecessor, former President Franklin Pierce, denounced Lincoln’s war in plain words in an extended oration in the capitol at Concord, New Hampshire. (A few years back, I attempted to get hold of this speech, which has not been seen by any of Pierce’s biographers. I found that a copy did not exist in the state of New Hampshire. My colleague Scott Trask finally located the only surviving text in an obscure antiwar New York paper.)

The predominant historical perspective among American historians today is that imported by communist refugees from Europe in the 1930’s. American history is now Ellis Island, the African diaspora, and Greater Mexico, and Old America has almost disappeared from attention except as an object of hatred. For today’s historians, unlike James Buchanan, Southerners are not fellow countrymen and real people but class enemies who should have been destroyed.

We are told that Lincoln was opposed by only a few sneaking traitors and stupid Irishmen who were worried about competition from black workers. In fact, most of Lincoln’s respectable Republican supporters disliked black people as much as the Irish did and made hysterical and successful efforts to keep any people freed by their armies from settling in the North, even temporarily. Republicans always blame labor for anything that goes wrong. The Lincolnians never fully trusted the Northern public and maintained power by lavish enlistment bounties, wholesale warrantless arrests, newspaper suppressions, army control of polling places, physical assaults on dissenters by Republican mobs in cities like Philadelphia and Chicago, and making sure that the draft weighed heavily on the poor but not on the well-to-do and articulate.

In fact, there are quite a number of good books on various aspects of the times that cast doubt on the innocent holiness of Lincoln’s cause. But they have made no impact on the popular mind. One writer recently stated that Franklin Pierce opposed Lincoln because Pierce was “a mean drunk.” Apparently, opposition to Lincoln can only be explained by bad character and bears no relation to the facts of the case.

Our greatest event, the war of 1861-65, has brought about some fiction and poetry, but perhaps not nearly as much as might be expected of such a cataclysm. There is a pretty good novel about General Lee’s horse and some good poetry about the Lost Cause, but nothing of the kind, as far as I know, about the Union side (although much of the “historical” writing about Lincoln certainly qualifies as “creative literature”). The South does better, especially on the home front: Fire and sword at the threshold are more interesting than self-righteousness and moneymaking.

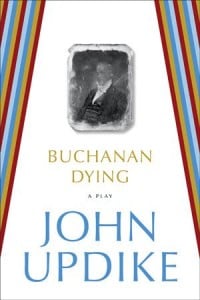

Yet the late John Updike, a preeminent fictional chronicler of 20th-century urban Americans, made an outstanding contribution to the literature inspired by the War in his play Buchanan Dying, newly republished and replete with understanding of James Buchanan and his times. This is not too surprising when we remember that Updike was a product of Old America, born and raised in Buchanan’s home country. He wrote in explanation of his attraction to the subject of the only Pennsylvanian president that it was “homage to my native state, whose misty doughy middleness, between immoderate norths and souths, remains for me, being my first taste of life, the authentic taste.”

Moreover, his background contains that forgotten remnant of the old dissident North. He tells us that his grandfather “spoke of Lincoln as someone who had personally swindled him”:

Through his Democratic prejudices I looked back, unknowingly, into the Jacksonian Democracy—anti-tariff, anti-bank—whereby America’s yeomen, north and south, took power from the seaboard aristocrats and bankers. Four decades later under the stalking horse of abolitionism, these same urban forces, swollen black and mighty, took power back.

The grandfather also remembered abolitionist Quaker neighbors who took in fugitive slaves to do unpaid farm work and, when winter came, turned them out to make their own way to Canada.

Updike was a good historian. From his Foreword and Afterword we see that he did his primary research and that he thought hard and well about the fundamental problem of reconstructing the past—telling a story that is both meaningful and true from always limited evidence. In the flashbacks visited upon the dying Buchanan in 1869 we get a convincing view of the man and his times. As one observer commented, Buchanan’s only quality was the lack of all qualities. His career was that of a classic politician whose indirection and cautiousness had put him into many high offices. His very blandness was responsible for his election as president in a time of conflict. By the time of the secession crisis he was 70. There is also a suggestion of the sociopathy of the successful politician—outwardly charming and affable, yet a man, as a contemporary put it, with no heart. He never married. There was an engagement early on. The young lady broke the engagement and shortly after died, a probable suicide.

Had Buchanan been a statesmen rather than a politician, and had his Jeffersonian principles been real rather than window dressing, he just might have been able to work out some way of avoiding war in the four months between Lincoln’s election and inauguration. That, and not his refusal to attack the South, was his failure. There are many indications that the great conservative heartland between the Deep North and the Deep South wanted only peace. Such an arrangement would have bound the Republican juggernaut of economic agenda and office-seeking, and perhaps that was too much to hope for. Anyway, Buchanan dithered and exercised no leadership at all. He won the eternal opprobrium of the North for the wrong reasons, even though the South had more reason to hate him than the North, because he had violated his own pledge to maintain the military status quo pending a political settlement.

Leave a Reply