“It was wonderful to find America, but it would have been more wonderful to miss it.”

—S.L. Clemens

In California, two brothers ages 20 and 15, murdered their mother and then cut off her head and hands, after which they were seen trying to unload a package with a foot sticking out of it into a dumpster. Her body was later found in a ravine; her head and hands were discovered in the boys’ bedroom. She had been heard screaming at her younger son about house-work—and then there was silence. The boys got the idea from the last episode of the fourth season of The Sopranos, in which Ralphie Cifarello is killed by Tony Soprano and then relieved of his head and hands to make identification difficult. Though there seems to have been a rush to blame television—specifically, The Sopranos—for this crime, I have a different interpretation: No mother, whether living in California or not, should, in the present environment, raise her voice at her son about housework—or anything else, for that matter. (Am I the only person who remembers the Menendez brothers?)

Shown on HBO for the last four years, The Sopranos has been a megahit. The series has attracted a devoted audience and given rise to extended commentary and analysis. These books address themselves to the first three seasons of The Sopranos and, thus, neglect the relative disappointment of the fourth season. There was a falling-off of tension, and, for many, the final violence did not justify the tedium of the wait. Nevertheless, die-hard Soprano devotees are hoping for a big finish in a fifth and final season, and there has been talk of a feature film. The story of The Sopranos is not over.

Having seduced a mass audience with insidious appeal, the show has made the opprobrium that has been attributed to it seem irrelevant. These objections come in two forms. One is the aversion to graphic sex and violence and to obscene language. There is a lot of both on the show, but the complaint is, finally, a weak one, for two reasons. First, the objection to sex, violence, and obscenity was steamrolled by Hollywood and popular culture in the 1960’s and since. Second, violence and bad language in The Sopranos are controlled by contextual irony. To present is not to advocate; otherwise, we might have a case for censoring Shakespeare (as has indeed been done). Ultimately, this is an objection to television itself, which had discreetly embraced extremity long before The Sopranos came along. The show is not the problem but the solution to the problematics of television, being more “moral” and more “real” than the routine obscenities broadcast by buffed bimbos with collagen-puffed lips, who daily recite more grossness on the news than is displayed by Tony Soprano and family.

The second, and more interesting, objection is that The Sopranos stereotypes Italian-Americans. Owing to a tradition of gangster movies, Italian-Americans have been given a raw deal by popular culture. This limited and limiting view, however, tends to play to the political maneuvering of identity politics. After all, it was the mobster Joe Columbo, Sr., himself who organized an Italian-American Defamation League and was shot at a rally of the propaganda front that he had the gall to gather. (So much for self-deception in playing the victim card.) The stereotyping is the point, not beside the point: The characters are trapped in their own limitations. Besides, the success story of the Italians in America is manifest, and, for every Michael Corleone, there is a Ray Romano. The sensitivity of some Italian-Americans seems excessive when we consider the American obsession with Italian cuisine and music, and, even more, the American obsession with sagas of the Mob. That fascination is more sympathetic than indignant, and it has been for a long time.

Dramatic representation is not the same thing as sociological statement—or, if it is, then it is to be deplored as bad art. Macbeth is not a slander on the Scots, nor is The Mikado a statement about Japan. And this principle holds true for The Sopranos, which is why so many viewers have instinctively felt that the show is not just a work of art but the best thing ever created for the coarse medium of television. The show is a trope rather than a statement of an ordinary kind, and this is something that most people accept without being aware of it. Add to that the particular reflexive quality of the discourse characteristic of this show, which has a way of preempting criticism. In the world of The Sopranos, ethnic stereo-typing is explicitly discussed—and dismissed. (The thugs love The Godfather, and one of them wants to be a Hollywood screenwriter.)

The show’s writing, however, is even shrewder than this suggests. Episodes dealing with ordinary social relations—getting the kid into college, talking to the priest, handling Wall Street investments, talking to the college dean, negotiating with the soccer coach, taking the wife out to dinner, etc.—all point up American

society itself as a scam and a shakedown, a laid-back Cosa Nostra, and make the straight-forward thugs seem normative. The postmodern texture of the show’s continuity, the weird poetry of the language, and the materialistic fetishism make The Sopranos engrossing but difficult to interpret. The uneasy mixture of humor and horror, the mixed effect of outrageous juxtapositions, and the playful music of misapprehensions and mistakes establish patterns that are a challenge to untangle, even if they are compelling to experience.

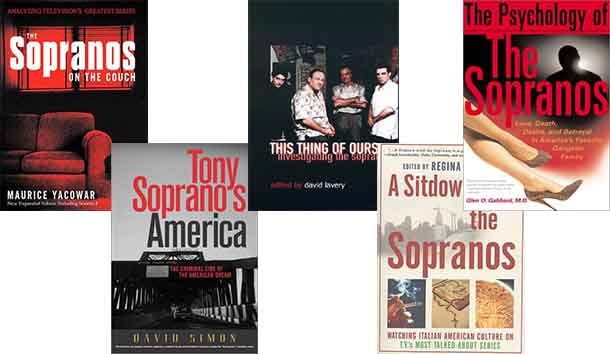

Some of the books that the series has elicited can be quite helpful. Glen Gabbard’s The Psychology of the Sopranos is not my cup of tea, but it is a successful and appealing study nonetheless. As an extensively published professor of psychiatry—he is the joint editor-in-chief of the International Journal of Psychoanalysis— Dr. Gabbard relates to The Sopranos in a way that the show, whose central image is Mob-boss Tony Soprano seated opposite Dr. Jennifer Melfi (she of the legs, the short skirt, and the rather affected professional manner), invites. Nothing in the series is better than Tony’s shrewd responses to her cues and the intelligence he manages to project from behind his blustering manner. A Freudian analysis throughout, Gabbard’s book is a graceful and insightful study that opens up the show, as well as the possibilities of therapeutic engagement. The analysis of Tony’s relationship with his monstrous mother, Livia; with his New Age sister; and with his wife and children only show the care with which the show is constructed. Perhaps I am wrong to be surprised to report that Gabbard’s is, by far, the best written of these studies of The Sopranos.

While Regina Barreca’s symposium has the advantage of an Italian-American focus, this does not necessarily yield the best results. These eight essays by Italian-Americans are sometimes imposing (the best is by poet, novelist, and biographer Jay Parini, a professor at Middlebury) and sometimes not (the worst is by Sandra M. Gilbert, madwoman in the attic). Parini’s emphasis on satire lends strength to his considerations, but, on the whole, the emphasis on ethnic distinctions is less productive than you might expect.

Maurice Yacowar’s The Sopranos on the Couch is the most obviously useful treatment of the phenomenon that I have seen, and it is the book on The Sopranos to have, if you are having only one. Though a bit slapdash in execution, Yacowar’s book is the most detailed and thorough of the five and contains a catalogue of three years of episodes, which are outlined and explicated. The pursuit of significant detail is clever and revealing (as in the analysis of the imagery of fish); the book amounts to a reader’s guide to The Sopranos, which Yacowar treats as though it were serious fiction or poetry while leading us to the conviction that such a treatment is appropriate—a remarkable conclusion in the case of a television series.

David Lavery’s collection is the most obviously academic; even so, it has its uses. For example, This Thing of Ours includes a catalogue of intertextual allusions that helps to nail things down that tend to drift in memory. On the whole, however, these 18 essays have sliced the sopresata too thin. There are studies devoted to the contexts of television history and the tradition of gangster films, to Canadian and British receptions of the show, and images of body weight and food. Missing from this collection, however, is some of the zest that the show suggests—the sense of gusto that is captured by Gabbard and Yacowar.

The least appealing, and most appal-ling, book about The Sopranos I have seen is David Simon’s. His volume uses the show as little more than a platform for a leftist rant about the history and culture of America, so that what we get is not Tony Soprano’s America but David Simon’s—and who needs it? While it is true that crime is a national metaphor in the series, Simon’s treatment is a disconnect, because he has no grasp of the tone of things. For pages at a time, as Mr. Simon lectures about Enron and the environment, the show disappears altogether. Where is the laughter, no matter how dark? Where is the fun, not to mention the sorrow and the pity? Anyway, as far as corporate depravity goes, Ralph Nader does it better. Simon’s sermonette is oddly skewed: If he valued irony, he would know that reform groups are only another set of con men and shakedown artists, as not only American history but episodes of The Sopranos indicate.

Having learned something, I hope, from the best pages in these books, I am not yet completely satisfied that the measure of The Sopranos has been taken. Some of the reflections on irony are good, but they do not go far enough, and sometimes they are prematurely sophisticated. The best thing about the show is what you see, and though the visual aspect of the series has been felt, it has also been neglected. The very image of the Sopranos’ North Jersey “McMansion” provokes a smile or a smirk. The “open” design and the overdone kitchen are exquisite in their banality. The hapless Sopranos are living the American dream, but that dream is a nightmare in terms of domestic furnishings alone. We may add to the visual catalogue the personal appearance—the clothes, hairdos, and body language—of the various characters. As embodied by James Gandolfini, Tony Soprano is too much, and you know him even before he opens his mouth. His hulking demeanor is swathed in shirts that would provoke laughter if worn by anyone else. His wife, Carmela, is also a piece of work, with her hair and her sports clothes and her breathless accent. These two represent the unsuccessful move into the upper-middle class, of course. Others regress to type, and perhaps the most superb icon is “Paulie Walnuts,” who seems to have disappeared into the image of himself. To know him is to love him: pompadour, tanning treatment, and all. And why should not the actor, Tony Sirico, who plays Paulie Walnuts have disappeared into the image of himself? He is well compensated for doing so. Tony Sirico was arrested 28 times and sent to jail twice—for a total of seven years—for armed robbery, and he has a bullet scar on his leg to show that he was once almost a “made man.” So much for stereotyping.

More attention has been paid to what you hear on the show, and the “offensive language” indeed includes many puns, images, various ironic juxtapositions, bathetic collapses, and malapropisms. Instead of “There’s no stigma these days,” we have “There’s no stigmata these days.” (That’s easy for you to say, and you can say that again.) Instead of Machiavelli’s The Prince, we get “Prince Matchabelli” (through Cliffs Notes). The beautiful Gloria, Tony says, looks like “one of those paintings by Goyim.” Tony insists that he is not “Hannibal Lecture,” and his son A.J. is sure that God is dead because “Nitch” said so. This “foregrounding of the utterance” has to be remembered in responding to all the gutter talk, for most of the profanity has a quality of parody, of the apprehension of various levels of culture by the hidebound and the classbound. Again and again, the blue-collar mentality, fortified by wads of cash, crashes as it fails to absorb precisely the references and values of the bourgeoisie into which the swag seemed to have promised entrée. This pattern is an old one in American and British literature. But, as in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and episodes of the Bowery Boys, the irony cuts both ways. The tough-talking thugs are more honest than the haute bourgeoisie and more truthful as well, and, finally, the Men of Respect earn something of that, along with some sympathy for the suffering imposed by their limitations. These patterns of language and value remove the pseudo problem of ethnicity from consideration of The Sopranos, for what is benighted about the mobsters is what they have in common with their viewers, not what they don’t.

Tony Soprano and his families are a slap in the face not only to the ordinary American sensibility but to the smiley-face pabulum of television itself. Insofar as the show is provocative, we can only affirm against the background of a “vast wasteland”: the worse, the better. A distorting mirror is required for a distorted society, as the show’s designer, David Chase, well knows. If The Sopranos is a text rather than a snooze, it is also necessarily a test.

[The Psychology of the Sopranos: Love, Death, Desire, and Betrayal in America’s Favorite Gangster Family, by Glen O. Gabbard, M.D. (New York: Basic Books) 191 pp., $22.00]

[A Sitdown With the Sopranos: Watching Italian American Culture on T.V.’s Most Talked-About Series, edited by Regina Barreca (New York: Palgrave Macmillan) 179 pp., $12.95]

[The Sopranos on the Couch: Analyzing Television’s Greatest Series, by Maurice Yacowar (New York & London: The Continuum International Publishing Group) 204 pp., $18.95]

[This Thing of Ours: Investigating the Sopranos, edited by David Lavery (New York: Columbia University Press) 285 pp., $17.95]

[Tony Soprano’s America: The Criminal Side of the American Dream, by David Simon (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press) 274 pp., $25.00]

Leave a Reply