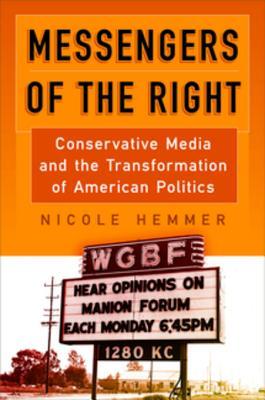

Messengers of the Right: Conservative Media and the Transformation of American Politics, by Nicole Hemmer (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 320 pp., $34.95). This very readable and otherwise excellent book is a history of the first generation of what the author calls “media activists,” conservatives who refused to work for mainstream periodicals and broadcasters and, in order to establish and guarantee their intellectual independence while influencing the course of American politics, founded the magazines, publishing houses, radio programs, and radio stations necessary to accomplish this. Messengers of the Right, the author says, “explains how conservative media became the institutional and organizational nexus of the movement, transforming audiences into activists and activists into a reliable voting base.” Nicole Hemmer gives particular emphasis to the careers of the broadcaster Clarence Manion, Henry Regnery the book publisher, and William Rusher, publisher of National Review, as “they evolved from frustrated outsiders in search of a platform into leaders of one of the most significant and successful political movements of the twentieth century,” in part by delegitimizing “the legitimacy of objectivity” and replacing it with ideological integrity. While populism was a means of bridging the divide between the conservative elite and the conservative grassroots, for the elite it was always, and chiefly, she says, “a linkage to the past.” Excellent in itself, Messengers of the Right can sensibly be read as a companion volume to George Nash’s The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945.

What Is Populism?, by Jan-Werner Müller (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 123 pp., $19.95). This small book considers what the author presents as “Seven Theses on Populism.” First, populism is neither “real democracy,” as Christopher Lasch argued it is, nor a pathological movement promoted by irrational people. It is, rather, “the permanent [though sinister] shadow of representative politics.” Second, true populists are not only antielitist, but antipluralist as well, believing that they alone represent “the people.” Third, populism is less the perceived will of the people than it is “a symbolic representation of the ‘real people’ from which the correct policy is then deduced. This renders the political position of a populist immune to empirical refutation.” Fourth, in demanding referenda, populists “simply wish to be confirmed in what they have already determined the real will of the people to be”; in other words, populist referenda are a simple business of QED. Fifth, populists can govern, but always corruptly. Sixth, though populists are “a danger to democracy,” one can debate with them: that is, “take the problems they raise seriously without accepting the ways in which they frame these problems.” And seventh, populism can be an indicator of the failures of representation—the possibility of which governments should consider, while reaffirming the moral superiority of a pluralist society to an exclusivist one. Müller further criticizes populism as “a particular moralistic imagination of politics” that refuses to recognize the legitimacy of the opposition—characteristics that any populist would be justified in arguing are shared at least equally by liberalism.

Le gouvernement du désir, by Hervé Juvin (Paris: Gallimard; 276 pp., €22,00). This excellent, though rather repetitive, book begins by deploring the end of romantic love in the modern world and its replacement by sheer physical desire that casual sex appears to satisfy, and goes on to describe a civilization in which desire and its satisfaction have come to dominate not only the consumer economy, which works relentlessly to create further desires, but also government, which uses and profits from that economy. “Under the exigency of the rights of man,” Juvin writes,

which advance the arrival of the absolute individual, desire becomes the motor of history—of our history. And it has organized the unconditional surrender of our societies to the economy—which needs slaves, which demands the opening up of borders, which promotes the extinction of amorous passion . . . as it disposes of the satisfactions of family life, of sexual reproduction, and everything that eludes industry, the law, the toll-man.

While claiming to liberate individuals from all social constraints, in fact desire delivers them up to conformity and transforms them into a mere abstraction. Today’s totalitarianism is the “monstrous child of ‘no limit,’ of the compulsion to change the world—the two commandments of modern liberalism.” “Desire” is another name for “globalization”—and the sure means of exploiting and ultimately destroying the natural world. In its place, Juvin argues for “a revolution of political desire”—that is, the return to the true political life that Pierre Manent has called a necessary condition of Europe’s continued existence; a “revolution of survival” on behalf of “durable man in a durable world.” Juvin understands modernity as the annulment of the future; to be modern, he says, is to be on the side of death. The sole way out of modernity, and into life, is “the rediscovery of life as it is, magnificent and sordid, delightful and tormented, the only love which can last for the free men that we will then be.”

—Chilton Williamson, Jr.

Leave a Reply