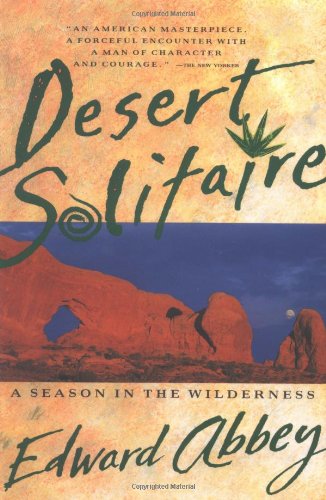

In spring, my thoughts turn first to the Southwest, that most beautiful and haunting part of it especially, the canyon country of southeastern Utah. There was a time when I pulled my horses down there every year toward the end of March and spent a week or ten days riding and camping south of Moab in the vicinity of the Colorado River. Whether I’ll manage a visit this year is uncertain, so in the meantime I’ve returned to the finest book ever written about the region, Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness (1968)—by my late friend Edward Abbey, of course. Reading it is as close as one can ever get to this dreamlike region without actually being there.

Abbey describes his work as an evocation, not an “imitation.” “I have tried to create a world of words in which the desert figures more as a medium than as material.” The book is an account of the two six-month seasons (elided to a single literary season) spent by the author as a seasonal park ranger at Arches National Monument north of Moab. Though Abbey drew upon his journals to write this book, the format he employs is a storyteller’s, an essayist’s, and at times a polemicist’s, not a diarist’s. Though he could be amusing as a novelist (The Monkey Wrench Gang, etc.), the novel was not really his métier: Not only does Desert Solitaire show him at his best, it his best book. (The two are not quite the same thing.)

Edward Abbey was one of the last of the Jeffersonian “conservatives”; that is to say he was an old-fashioned republican, an enemy of tyranny, including that form of tyranny called industrialism that is responsible, directly or indirectly, for nearly every tyrannical aspect of modern society, and a lover of freedom of the human and natural sorts. Abbey wanted humanity and nature unbound to the mutual benefit of them both, believing that “wilderness is a necessary part of civilization.” He was a mystic, though not a religious man. “I dream of a hard and brutal mysticism in which the naked self merges with a nonhuman world and yet somehow survives intact, individual, separate. Paradox and bedrock.” For him, glorious vistas of river, plain, and distant mountains failed “to proclaim the glory of God.” Instead they confirmed him in the conviction that “There is nothing here, at the moment, but me and the desert. Why confuse the issue by dragging in a superfluous entity?” In this respect, Abbey belongs irremovably within the a-theist tradition of American “nature writing” (a term he loathed) as it descends from Thoreau. But he was a far better storyteller than Thoreau, owing to the warm, comradely human presence supplied by like-minded friends who shared his adventures, and his taste for adventure—even danger—itself.

We bounce [in a pair of lashed rubber boats] over a series of minor ripples and the boat picks up speed. There is a corresponding excitement in the sky: the storm that has seemed potential for days is gathering above in definite form—wild gray scuds of vapor, anvil-headed cumuli-nimbi, rumbles of thunder running closer.

—Chilton Williamson, Jr.

[Slideshow Image: By Adrille (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0]]

Leave a Reply