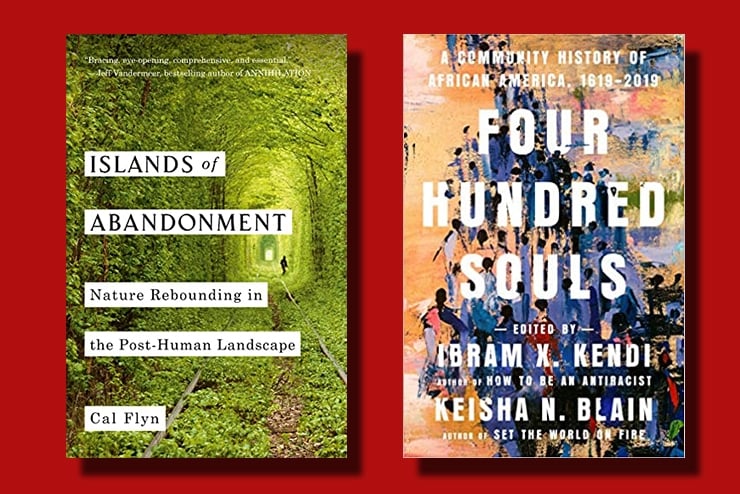

Islands of Abandonment: Nature Rebounding in the Post-Human Landscape, by Cal Flyn (Viking; 384 pp., $27.00). In our era of ecological angst, many are desperately seeking strategies to mitigate human damage, but Scottish writer Cal Flyn suggests a holistic new way—one that is simultaneously haunted and hopeful—of seeing these problems. She writes often in sorrow, sometimes in righteous anger, but always in a spirit of humanity and realism. She visits real and metaphorical islands—from Chernobyl to Paterson, N.J. and the Caribbean to Tanzania—that have been devastated by depopulation, industry, invasive species, pollution, radiation, volcanoes, or war only to find flora and fauna rebounding in richly unexpected ways. Utilizing insights from Celtic mythology to neuroscience, and E. O. Wilson to T. S. Eliot, she marvels at rare orchids blooming on a shale-oil spoil heap. “A self-willed ecosystem is in the process of building new life … starting again from scratch, and creating something beautiful.” Earth is a stupendous alembic, in which new and old ingredients are always alchemizing. Or, as Horace noted famously, “You can drive out nature with a pitchfork, but she keeps on coming back.”

It is something like a sacred trust to do what we can to protect the environment. But we shouldn’t despair. Even if the Amazon rainforest is under reckless attack, forests elsewhere are advancing. Wild horses graze former farmland; wolves pad down deserted streets; owls nest in old factories; indigenous species adapt to or even prevail against invaders; and toxic dumps can sport resilient new growths. Domestic cattle left behind soon learn to live without us, and the least promising postindustrial wastelands can become havens for species otherwise almost extinct.

There is little real unsullied wilderness left in the world (there really never was as much as we thought), but new wildernesses are always forming, if we allow them. There may even be new forms of beauty, if we look properly, in the moldering skeletons of houses, ships’ graveyards, or monumental works of “land art,” like Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, in Utah. Cities like Detroit, so often seen as evidence of avoidable failure, may really be almost as organic as animals, with inherent natural life spans in which individual buildings have a “domicology” of change and decay. As Vladimir Nabokov observed in 1952, the future is “the obsolete in reverse.”

We have depleted and despoiled the earth, but even some of our most destructive actions may be ameliorated or selfremedying in time, especially if we can let go of outdated aesthetics or imperious delusions of control. “This is a corrupted world,” she concludes sagaciously, “long fallen from a state of grace—but it is a world too that knows how to live.”

(Derek Turner)

Four Hundred Souls, eds. Ibram X. Kendi and Keisha N. Blain (One World; 528 pp., $20.00). Nietzsche described a psychopathology called ressentiment in which an outside tormentor is perceived as causing all of life’s misfortunes. Readers would do well to keep their Nietzsche close to hand while thumbing through the essays of antiracist activists in this book.

Four Hundred Souls’ conceit follows directly from The New York Times’ “1619 Project,” which sets a new founding year of America for the anti-racist mythology.

Ninety writers, mostly journalists with no scholarly expertise, take on five-year chunks of four centuries of black suffering. What follows is a remarkable monotony. America has been 400 years of endless affliction and terror meted out by an unchanging and unlimited power of demonic fury utterly bent on the elimination of all things nonwhite. The reader is unsurprised in such a book to be informed that the American Revolution and the production of the country’s founding documents were racist nonevents because they did not immediately end slavery.

In another chapter, we learn that Christianity in the United States “could have been a force for liberation … [but instead] became a cornerstone of white supremacy.” The fact that a Christian moral worldview has long been a dominant feature of American culture and that Christian justifications for both liberation and continued slavery have existed is too nuanced for such a book.

All is race, identity, and ressentiment. Nothing has changed. Sure, blacks are no longer forced to labor in the fields under yoke and whip, but voluntary housing segregation and mass incarceration remain, and aren’t they the same thing in a different mask? Black males are represented in medical schools at a percentage below that of their presence in the broader population; “bias” is the only possible cause. A history of black America requires more than a deceitfully ideological attempt to pretend not a single thing has changed for blacks in 400 years. It would celebrate substantive black accomplishment and excellence instead of wallowing in the morbidly ressentiment-driven focus on black life as forever determined by a now nearly extinct enemy. None of that is to be found in this miserable, small-minded collection of unmerited indignations.

(Alexander Riley)

Leave a Reply