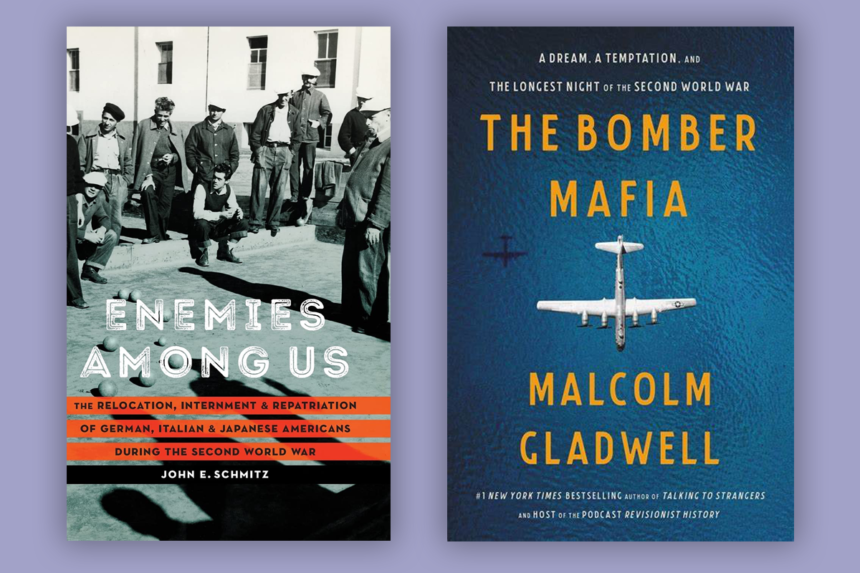

Enemies Among Us: The Relocation, Internment, and Repatriation of German, Italian, and Japanese Americans During the Second World War, by John E. Schmitz (University of Nebraska Press; 430 pp., $65.00). How can we possibly avoid history’s repetition when we don’t learn anything from it in the first place? For 50 years after World War II, historians cited racism as the sole reason for the United States’ internment of Japanese-Americans. The academic obsession with racism has undermined our understanding of history.

Morton Godzin’s Americans Betrayed kicked off our self-loathing in 1949. Schmitz’s book revises this simplistic interpretation of American internment policies during WWII, finding that “the government interned more German and Italian Americans than Japanese Americans, arrested them in greater numbers, and relocated members of all three enemy groups.” Why haven’t scholars more deeply probed Roosevelt’s wartime policies, which called for the removal of German and Italian enemy aliens and citizens? If something more than just fears of the Yellow Peril drove the feds to arrest the “Chianti, Catholicism, and Crime” squadristi and their sauerkraut-eating Freunde, what was it?

Schmitz identifies several long-ignored factors. After Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt invoked the specter of a fifth column with subversive designs on a terrified nation. Not to be outdone, our perennial friends in the media amped up the threat posed by German-American Bunds. In reality, just 450 of Chicago’s 700,000 German-American residents counted themselves members of those homegrown Nazi groups.

Internees also served as bargaining chips to secure the release in December 1943 of some 1,500 Americans imprisoned by the Japanese. They told “chilling tales of Japanese cruelty” that included “lack of nutritious food … general filth … and, finally, the brutal Jap attitude.”

American authorities also argued with some reason that internment protected vulnerable populations from vigilante attack.

Warring countries have long detained citizens and enemy aliens for numerous reasons, of which racism is just one. But when scholarship focuses exclusively on racism, we miss timeless history lessons about media duplicity, public hysteria during wartime, and the practical reality of prisoner exchange. Schmitz’s work untangles the psychological, political, social, and, yes, racial forces that culminated in a sad historical episode.

(John Greenville)

The Bomber Mafia: A Dream, a Temptation, and the Longest Night of the Second World War, by Malcolm Gladwell (Little, Brown and Co.; 256 pp., $27.00). This is a diffuse, peripheral military account drawn from Malcolm Gladwell’s “Revisionist History” podcast series. The book’s title refers to aviators at the Air Force Tactical School in Montgomery, Alabama. The “dream” is that of Donald Wilson, a flier who believed that strategic bombing, using an analog-computer bombsight developed by Carl L. Norden, could simplify and shorten wars. The “temptation,” General Curtis LeMay’s, is to drop napalm on enemy cities. The “night,” March 9, 1945, is when some 270 B-29s dropped incendiary bombs over Tokyo.

Precision bombing of Japanese factories and storage depots had begun from Saipan (Mariana Islands) in November, 1944. Results were disappointing. In January, General Haywood Hansell, who was loath to use the volatile incendiary gel, napalm, was replaced by Curtis LeMay, who adopted it. While precision bombing continued, area firebombing raids multiplied. By mid-June, six large industrial centers had been devastated. By mid-July 60 percent of the ground area of Japan’s largest cities was burnt out.

These attacks were not without effect; yet Japan’s divided central government showed no sign of discontinuing the war. Recognizing the tragic utility of the strategy after the war, Japan honored LeMay in 1964 with its highest award. Gladwell, however, aware of the Christian doctrine jus in bello (“the lawful waging of war”), honors Hansell more than LeMay.

Gladwell, a popularizer who calls himself a social psychologist, is a New Yorker contributor and author of bestsellers. In The Bomber Mafia, he has devised what appears to be a new subgenre of nonfiction: the podbook or podcast-book, in which the material is first derived from the video essays and interviews he streams weekly on the Internet. Few critics have yet discussed this innovative form. “While I was reporting this book” is Gladwell’s odd phrasing of his process in his “Author’s Note,” which suggests the amalgamation of the initial oral documentary with print text.

The audience for this podbook includes, presumably, young-to-middle-aged readers who may be devotees of Gladwell’s podcasts and the accessible historical revisionism that is his trademark. A telling appreciation comes from a London Times reviewer, quoted on the dust cover, who called Gladwell “a rock star of nonfiction.”

Perhaps Gladwell is more like an easygoing, popular professor who, instead of lecturing formally, chats with his students, trying to keep them awake by anecdotes, asides, digressions, and frequent reminders of who’s who and what’s been said. It’s a TED talk, in book form. No need to be very alert, or to read closely. So, how do you like your history?

(Catharine Savage Brosman)

Leave a Reply