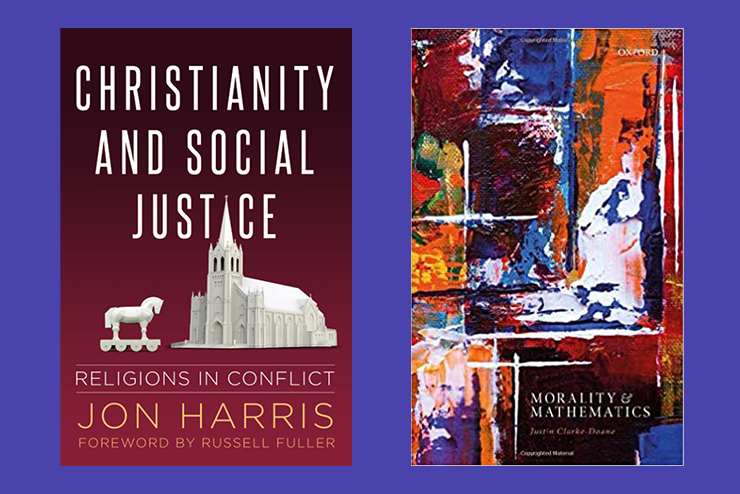

Christianity and Social Justice, by Jon Harris (Reformation Zion Publishing; 160 pp., $14.99). In this slim discussion of social justice and its relationship, or non-relationship, to Christianity, Jon Harris, a Protestant theologian and Baptist minister, addresses the topic long after he observed the “incursion made by the social justice movement” into the Baptist seminary where he studied. There, “some of us felt we were swimming in a sea of political rhetoric, but everyone acted as if it were normal and nothing was happening,” he writes.

Harris is struck by the fact that his own confession, with its belief in biblical inerrancy, was long viewed as beyond the reach of leftist cultural trends. Yet like the mainline Protestant denominations and Catholic progressives, it was in fact permeated by these currents and moving from older Social Gospel themes to the more recent “woke” morality.

Harris tries to show that the social justice movement has created a parallel universe of thought to the Christianity it is working to replace. It has produced its own gospel, metaphysics, and epistemology by selectively blending Marxism, a radically understood notion of “redistributive justice,” and intergenerational social guilt.

Harris is particularly perceptive in dealing with this last point. In the appendix, he presents a well-considered response to David French, a senior editor of The Dispatch, who quoted extensively from Hebrew Scripture to, as Harris writes, “defend the view that modern American Christians are complicit in ‘structural racism’ and possess an ‘intergenerational obligation to remedy historic injustice.’”

In his detailed response to French’s war against “systemic white racism,” Harris points out that in the Bible “each person will answer for his own actions. This does not mean that children cannot learn and repeat the sinful habits of their parents.” Rather the descendants “are punished for participating in the sins of their ancestors,” and not because of blood guilt.

Harris also notes that since French has no problem defending Drag Queen Story Hours at local libraries, in violation of specific prohibitions in Mosaic Law against men dressing and behaving like women, he is clearly not consistently upholding Old Testament teachings. Indeed he “has no problem stretching and selectively citing unique examples” to “bolster his argument for systemic racism.” One wishes Harris’s refutation were made more widely available.

(Paul Gottfried)

Morality and Mathematics, by Justin Clarke-Doane (Oxford University Press; 208 pp., $64.00). Many readers of this journal, I suspect, will be inclined to take a dim view of analytical philosophy, viewing it as a narrowly technical field that concentrates on trivialities while ignoring the “real questions.” Justin Clarke-Doane’s masterful new book shows that this stereotype is altogether mistaken.

The author, a philosophy professor at Columbia University, asks questions of central importance, such as whether evolutionary accounts of morality undermine moral realism, the view that moral judgments are true, independent of human thought and language, and how we can cope with disagreements in morality and mathematics.

In morality, Clarke-Doane maintains, we must come to a single decision in a given case about what to do. We cannot decide both to push a man into the path of a speeding train and at the same time not to push him. In his special sense of the term, morality is “objective,” which means that a single answer is required.

But there is always a gap between thought and action. Even if, for example, there is an “all-things considered” ought—or, something that mandates a certain action—or even if someone is fully motivated to do something, the question remains open of whether to do it. “Practical questions may remain open when the facts, including the moral facts, are settled,” Clarke-Doane writes.

One surprising point the author makes is that mathematics doesn’t consist of deductions from self-evident axioms. In fact, a great many of the standard mathematical axioms are hotly disputed among recognized authorities. In set theory, for example, many of the standard axioms, such as the Axioms of Replacement and Choice, are rejected by well-known authorities.

“It might be thought that the picture looks different if we focus on ordinary branches of mathematics, as opposed to set theory,” Clarke-Doane writes. “What about core areas which are commonly thought to be objective? Various theorists doubt plausible principles from core areas too.”

The book is dense and difficult—at least I found it so—and the author moves with great rapidity from one argument to another. Some parts of the book, though, such as the introduction and conclusion, are well within the grasp of lay readers, and those willing to make the effort will encounter a first-rate philosophical intelligence at work.

(David Gordon)

Leave a Reply