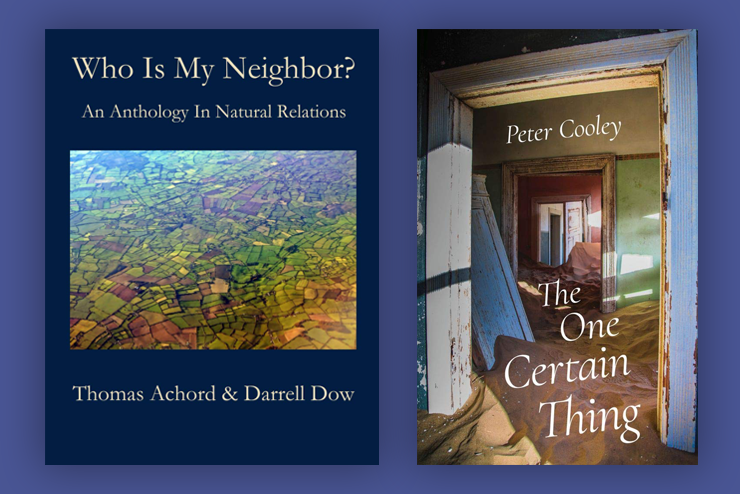

Who Is My Neighbor? An Anthology in Natural Relations, by Thomas Achord and Darrell Dow (584 pp., $24.99). The headmaster of a classical Christian school has teamed up with a statistician to collect and sort thousands of quotations pertaining to human relationships from myriad religious, political, and historic figures. The result is an invaluable reference for patriots with an intellectual bent, which shows how nationality, neighborhood, and kinship reflect natural law. The book’s historical quotes and references demonstrate that many of the sentiments now stigmatized as unthinkably “nativist” or “racist” have been taken for granted in every civilization, from classical China to ancient Israel to medieval France.

We discover, for example, Cicero cautioning the resident alien “under no condition to meddle in the politics of a country not his own.” Aristotle warns that “the reception of strangers in colonies, either at the time of their foundation or afterwards, has generally produced revolution.”

Achord and Dow have also compiled Christian sources from St. Augustine to John Calvin on the subject of man’s ties through kinship, as well as the thoughts of America’s Founding Fathers. His invocation of equality notwithstanding, Thomas Jefferson feared that “the importation of foreigners” would “warp and bias” America, rendering it “a heterogeneous, incoherent, distracted mass,” and so make it “more turbulent, less happy, less strong.” On this question of multiculturalism, at least, the sage of Monticello and his nemesis, Alexander Hamilton, could agree. “The influx of foreigners must, therefore, tend to produce a heterogeneous compound,” Hamilton said, “to change and corrupt the national spirit; to complicate and confound public opinion; to introduce foreign propensities.” George Washington counseled his countrymen “to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world” and to have “as little political connection as possible” with other nations.

Perhaps the most bitterly amusing and ironic quotes come from 20th century Democrats, who assured critics the Immigration Act of 1965 would “not upset the ethnic mix of our society,” as Senator Edward Kennedy soothingly put it. Nowadays it is forbidden to observe how wrong (or dishonest) Kennedy was, much less to frankly discuss the implications of our society’s ongoing ethnic transformation. It is to be hoped that through works like Who Is My Neighbor? at least a few people attain some idea of what the much-abused word community actually means.

(Jerry Salyer)

The One Certain Thing, by Peter Cooley (Carnegie Mellon University Press; 80 pp., $15.95). In “This Living Hand: A Visitation,” a poem from this outstanding testimony to a husband’s love for his wife and grief at her death, Peter Cooley writes about the crosses each wore. “Before they took your body to be burned/I scooped yours from your neck…/slipped it on mine.” He adds, “I wasn’t going to write this. It’s no poem./Maybe it’s just you, speaking to me again.”

Such are the tones and context—Christian, specifically Anglo-Catholic—in which the speaker draws on and illustrates faith, hope, and love, in highly original dialogic terms. Cooley, the author of 11 previous collections, is a recent poet laureate of Louisiana and is now Professor Emeritus at Tulane University. His usual form, free verse, is always well-crafted, the lines shaped to the thought or argument, the stanzas to its development. Displaying poetic skills developed over decades, he has complete command of his subject. Yet he is deeply engaged in it, “existentially,” journalists would write now. Far from showing Stoic indifference, the kind of poetic control Cooley demonstrates is both sign and means of emotional control over deep feelings. Yet in Cooley’s writing, the feelings remain raw, caught in their full contingency.

While aware of how much “the animal fact of death” shapes our condition, Cooley does not seek a facile conciliation with it. Though death is the “one certain thing,” confronting it is, after all, not simple. Initially, he must deal with the shock of discovering Jacqueline’s body one morning in March 2018, “splayed on the couch,/your tongue hung across your lower lip.” The material facts of this death at home are a terrible test, as are the social ramifications: besides undertakers, there are his children, living elsewhere, counselors (churchmen and lay), widowers, to whose fraternity he now belongs, and well-meaning neighbors, one recommending he get a girlfriend. All such help is of uncertain avail. He thinks likewise of departed family and friends who left him bereft and whose company his deceased helpmate may now keep.

Most of all Cooley deals, and wants to deal, with Christ, who is a third party in this drama of the soul. “Christ between us as I put down these words,/Over us, ahead, every whichway,/the nighttime in my room a part of Him.” While the deceased are not in human time, Christ is, there with the poet, “down-heaven.” While Jacqueline was alive, He “moved through them. … The cross—/the cross is still not finished with us yet.”

(Catharine Savage Brosman)

Leave a Reply