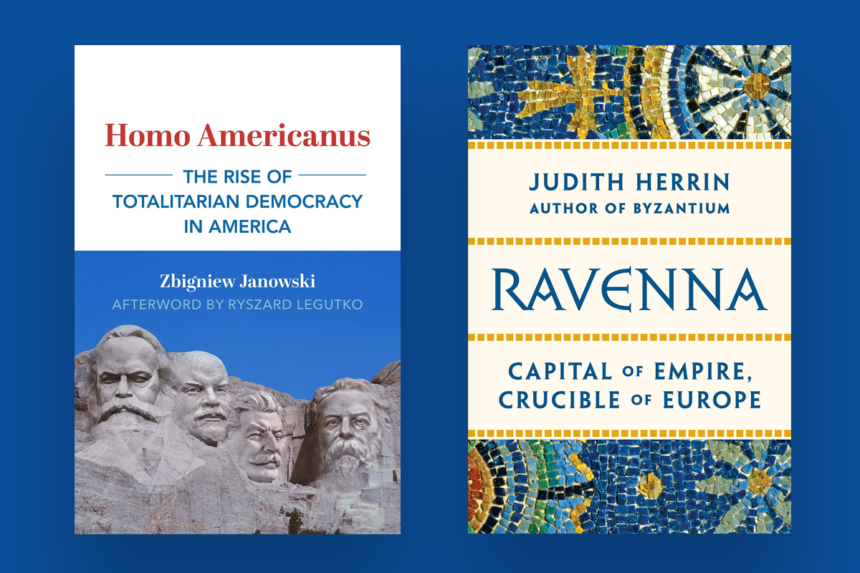

Homo Americanus, by Zbigniew Janowski (St. Augustine’s Press; 250 pp., $24.00).

Polish American political thinker Zbigniew Janowski examines the reasons that modern American democracy has taken a totalitarian turn. Contrary to the happy talk coming from establishment conservatives about the need to spread America’s so-called liberal democratic values everywhere, Janowski paints a dark but compelling picture of where America’s once strong constitutional institutions have gone. He depicts a country oscillating between moral arrogance and ritualized self-abasement, which can never quite decide whether it’s the salvation or bane of humanity, and which remains fixated on equality as the highest ideal.

Like his close friend Ryszard Legutko, who wrote the afterword to this volume and the insightful book The Demon in Democracy, Janowski does not worship at the altar of democratic equality. Moreover, he sees many of the cultural and social problems that beset present-day American society as having been affected by this democratic idolatry. Equality in democracy, argues Janowski, leads to a homogenizing process that destroys the individuality that democracy claims to defend, and which makes war on traditional hierarchically- based communities.

“1989 was not a moment of liberation but the moment when one collectivist ideology (communism) was replaced by another collectivist ideology (democracy),” Janowski writes. Both these egalitarian ideologies are the “children of the Enlightenment.” The question that Janowski addresses in the last chapter is:

[W]hether one can limit democracy’s expansion—which is equality’s engine—in a way that is consistent with the idea of democracy at the same time? To put it differently, can one limit equality to preserve democracy?

Since Janowski leaves his heuristic queries open, this reviewer feels free to note that the egalitarian democracy he so graphically describes represents a falling away from something much better. It is a denaturing of the constitutional republic upholding federalism and ordered liberty that marked America’s earlier phase. The United States was not always the quasi-tyranny it is now becoming. It started with a wellconceived political order, one that some Americans wish to return to.

(Paul Gottfried)

Ravenna: Capital of Empire, Crucible of Europe, by Judith Herrin (Princeton University Press; 576 pp., $29.95).

For crucial centuries, Ravenna was the capital of the Western Roman Empire, and then of the Ostrogothic Kingdom. More than its historic rival, Rome, it gave birth to late antiquity and the early medieval period—to Christendom, Judith Herrin argues. This view is not startling; contrast it, however, with respected treatments of the period one hundred years ago. In A History of Rome to A.D. 565 (1921), A.E.R. Boak identifies Ravenna as the Ostrogothic capital and notes its siege by Belisarius but dwells on it no further. James Harvey Robinson’s An Introduction to the History of Western Europe (1902) does not even mention it. Herrin’s reassessment underlines Ravenna’s singularity, which much previous scholarship has failed to recognize. The city endured despite its delicate position between Rome and Constantinople, between Roman Christianity and Greek Orthodoxy, and was ultimately firmly established with the mostly Arian Goths. Her extensive documentation, assembled over nine years, includes the study of ancient papyrus records in Latin. Correspondence and other documentary sources allow her to provide worm’s eye views of daily city life. While acknowledging a debt to Princeton historian Peter Brown, crediting him with expanding and correcting older views of Ravenna and the time period in The World of Late Antiquity (1971), she would like to replace his term “late antiquity” with “early Christendom.”

Herrin’s narrative begins with Diocletian’s reforms in the third century and ends after Charlemagne’s death in 814. Political and military developments, the stuff of traditional European history, constitute most of the story. Power, both goal and means, plays a tremendous role; the Christian creed notwithstanding, enemies are exiled, beheaded, blinded.

Architecture, sculpture, and mosaics furnish lasting evidence of the Ravenattis’ beliefs, tastes, wealth, and tolerance. That many buildings, monuments, sarcophagi, and decorations survived for centuries is remarkable. Some fell into disrepair, while others were altered for religious reasons, pillaged for their marble, or defaced in what Herrin calls “a form of forgetting.” More than 1,300 years later, Allied bombing raids pulverized the Basilica of San Giovanni Evangelista in August 1944.

Herrin’s study and its admirable illustrations are well worth readers’ attention, though the lengthy text contains some flaws. Her style is direct, but without storytelling charm. Reliance on awkward exposition and occasional grammatical errors are distracting in what is otherwise an informative and enjoyable book.

(Catharine S. Brosman)

Leave a Reply