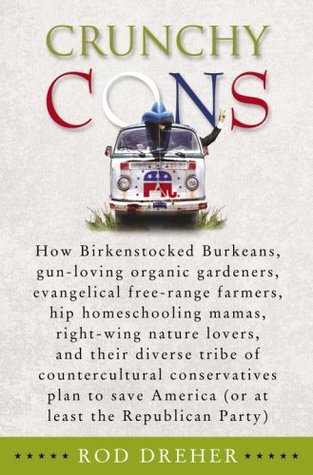

Rod Dreher’s book labors under a few handicaps. First, there is the cloying title and absurdly long subtitle. In addition, the cover features a cutesy picture of a VW microbus with a GOP elephant painted above the grille. The back cover features a “Crunchy Con Manifesto” that is a bit simplistic. “We are conservatives who stand outside the conservative mainstream; therefore, we can see things that matter more clearly.” However, the old adage about not judging a book by its cover applies here, because Crunchy Cons does merit serious attention.

The conservative movement, as currently constituted, can accomplish little more than elect Republicans, demonize Democrats and liberals, and turn execrable books by talk-radio hosts and syndicated columnists into best-sellers. Since politics has devolved into a team sport, many of the conservative rank and file are happy just to be “winning.” In Crunchy Cons, Rod Dreher looks at the deeper issue of whether conservatives are accomplishing anything of value.

Dreher’s cultural and political beliefs (he considers culture to be more important than politics) are informed by his Roman Catholicism. Specifically, many of the “crunchy” (if one must use the term) aspects of his beliefs are Catholic in origin. Crunchy Cons briefly retells the author’s journey from his childhood Methodism to agnosticism and finally to Rome. “To the extent that I can be called conservative,” Dreher writes, “it’s because I want to conserve the wisdom and humane traditions taught and celebrated in Catholicism—even if it puts me at odds with contemporary Republicans.”

In his discussion of man’s relationship with the natural world especially, Dreher demonstrates his willingness to stand at odds with contemporary Republicans. Goaded to reexamine his thinking by a reading of Matthew Scully’s Dominion, Dreher recounts how the simple fact of a fellow political conservative (formerly a National Review staffer and Bush speechwriter) becoming a vegetarian and an opponent of factory farming forced him to rethink some issues for himself.

It took about fifty pages of Matthew’s book for me to realize how closed-minded and dishonest I, a conservative, had been about animal rights and the environment. How often had I sneered at environmentalists to hide the fact that I didn’t really understand what they were talking about, and, more to the point, didn’t want to?

I can sympathize with Dreher because, for much of my adult life, I thought exactly the same way. It is very easy to find reasons to dismiss facts and arguments offered by people on the other side. (Dreher, who is hard on his conservative allies, notes nevertheless that environmentalists are guilty of similar closed-mindedness in ignoring the genuine fears ordinary Americans have about losing their jobs to environmental regulation.)

In expressing his concerns about environmental destruction, Dreher even treads on thin ice to denounce right-wing indifference to global warming. Few beliefs are more sacred to the current National Review crowd than the notion that climate change is simply liberal propaganda, regardless of the near-unanimous views of climatologists and the physical evidence of sinking islands and thawing permafrost. Citing a lament by Jeffrey Hart, a senior editor at NR, over the willingness of some right-wingers to see the world made into a giant Hong Kong, Dreher notes that “in a world such conservatives are helping to bring about . . . Hong Kong will capsize under rising oceans.”

Americans ignore the problem because, as President George H.W. Bush expressed it in 1992, “the American way of life is not negotiable.” By the “American way of life,” he meant our extraordinary levels of consumption and waste. Rod Dreher is not enamored of the American Way of Life, although he does not say so in so many words. After the attack on the World Trade Center, both Mayor Giuliani and President Bush encouraged Americans to go shopping. It would have been an ideal moment, Dreher suggests, for the President to call for a reduction in our consumption of energy, which does so much to fuel radical Islam—but no, there is the American Way of Life to consider, prompting what Dreher condemns as an appeal to the “crass spirit of the present age.” Perhaps in an attempt not to sound hypocritical, Dreher notes that, while “we have all benefited enormously from America’s economic progress,” the “problem is the way we relate to our material gains.” Americans have more and more stuff, yet “only a blind optimist would argue that we are a spiritually sound, morally strong, society of happy people.”

Americans are inundated with entertainment. In the age of the iPod and cell phones, one need never be alone or bored. The elephant in the living room, however, is still the television set. Dreher, who lived in the wilderness for several months to decompress after working as a TV critic a few years back, observes that, while the typical conservative complaint about television pertains to smut or violence (Brent Bozell and the Media Research Center are still obsessed with Janet Jackson’s nipple), the amount of time the idiot box consumes is a far more important concern.

By its very nature, television technology teaches us to experience the world as a series of fragmentary images. . . . [I]f a law were passed tomorrow granting Michael Medved, William Bennett and Pope Benedict XVI the power to control all television programming, our essential dilemma would change not one bit.

Crunchy Cons, in part, tells how Rod Dreher came to look at issues for himself instead of simply consulting the Red State/Blue State manual. Along the way, he examines the thought process that keeps people in ideological boxes and encourages them to demonize their enemies, often on the basis of cultural tastes or on hatred. Here, he describes his feelings before the Iraq invasion:

I remember the run-up to the Iraq War, listening to some conservatives arguing that there was no real evidence that Iraq threatened us, and besides, it’s an arrogant fool’s errand to set out to install a democracy in a country that has never known it. They made solid arguments from conservative principle, but I didn’t want to listen. I hated the Islamic terrorists who killed so many of our people on 9/11, and I hated the liberals who hated the war. USA! USA! Let’s roll!

For his efforts, Dreher has earned the ire of many fellow conservatives—not surprisingly, as he is extremely critical of his former allies, although he includes himself as an object of criticism. National Review Online set up a blog to discuss the book. The blog saw frequent appearances by John Podhoretz, who dropped in to sneer when he wasn’t accusing the other participants of being anti-American, and Jonah Goldberg, who cross-examined Dreher with a prosecutorial zeal. Maggie Gallagher, the marriage advocate, has posted an almost insultingly dismissive review.

Dreher is fortunate already to have left National Review for the Dallas Morning News. As Joseph Sobran and Bruce Bartlett could tell you, NR and the rest of the Movement Right are not especially hospitable these days to dissenters and independent thinkers in their midst.

[Crunchy Cons: How Birkenstocked Burkeans, Gun-Loving Organic Gardeners, Evangelical Free-Range Farmers, Hip Homeschooling Mamas, Right-Wing Nature Lovers, and Their Diverse Tribe of Countercultural Conservatives Plan to Save America (or at Least the Republican Party), by Rod Dreher (New York: Crown Forum) 259 pp., $24.00]

Leave a Reply