Americans love their lawns. They spend $40 billion per year—more than the gross national product of most countries—to create the perfect lawn. Taken together, all these lawns would cover the entire state of Kentucky. Lawns are everywhere, from trailer parks and executive mansions to businesses, churches, and recreational areas. American agronomists have created so many grass varieties that some types of lawn can be grown in all 50 states. The spread of lawns has steadily increased since World War II and has reached a frenzied peak during the last two decades, as aggressive suburbanization converts almost 400,000 acres of land per year to lawns.

Suburbanization is what really changed America’s attitude toward grass. The rapid spread of housing and mass transportation driven by cheap oil and newfound wealth created a landscape revolution. What was once a preoccupation for the wealthy quickly became a universal status symbol for an upwardly mobile nation. Before the lawn revolution, the average yard was a concatenation of shrubs, trees, weeds, and vegetable gardens, or simply plain dirt that was periodically swept. By the late 1950’s, these odd and eccentric yards, which varied greatly according to region and climate, were increasingly being standardized by the spread of grass. Lawns became so large and widespread that they spawned an entire industry providing machines, watering systems, chemicals, publications, and professional services to manage them.

Steinberg presents a number of reasons why Americans became lawn-obsessed. Grass is soothing. The deep greens and soft textures may have been particularly appealing to 1950’s America following a bloody world war and during an equally tense Cold War. Lawns are also comfortable and practical. Children and pets can romp, and adults relax, on the open turf. And they fit right into the postwar trend of the privatization of social life, providing a comfortable backyard retreat that replaced the front yard as the center of social activity. As Americans grew more isolated from their neighbors, the front lawn became a subtle, yet effective, formal barrier between house and street. And the better the lawn was maintained, the better the barrier. The lawn, furthermore, was the perfect outdoor outlet for Organization Man, who struggled all day in an increasingly complex world he had little control over. Once he fired up his lawn mower, however, he could achieve control and closure by trimming the flat expanse before him.

Because the lawn was a controlled environment, it was also a perfectible one. More fertilizer and watering, better equipment, or new grass varieties could always improve the turf. And for enthusiasts, the lawn became an obsession. The explosion of golf courses exemplifies this to the fullest. In America, there are 15,000 of these perfect lawns. Putting greens are the most meticulously managed landscapes in human history. Many require daily pampering. As a result, golf courses require armies of lawn-care specialists to maintain them and other parts of the course at optimum heights, hues, and textures. The more luxurious the course, the larger and more sophisticated the staff.

The obsession entails environmental costs. Golf courses are among the most polluted places in America because of the amount of chemicals they require. Most, the author quips, would actually qualify as toxic-waste sites. But a lush, green lawn looks natural and inviting, masking its deadly support system. Golf courses also use exorbitant amounts of water—especially problematic in desert climates where grasses are alien to the ecosystem. Some require almost 200,000 gallons per day, the equivalent of the normal water needs of 2,200 people. The same goes on a smaller yet more widespread scale at the neighborhood level, because of the watering and chemical requirements of 60 million household lawns.

More serious health hazards are associated with lawn equipment. There are 80,000 injuries and hundreds of deaths every year, most from lawn-mower accidents. The whirring blades of a rotary mower release three times the energy of a .357 magnum, a gun that can project a bullet through an engine block. Naturally, accident rates are highest among lawn-care workers, mostly low-paid and unskilled illegal immigrants nowadays, who operate large, complex, and dangerous machines on a daily basis. The lawn-and-garden industry has one of the highest death rates of any profession—15 per 100,000—higher even than that of police officers!

Ted Steinberg is an environmental historian, yet American Green is anything but academic. It is good social history, written in a humorous and engaging style. The author is at his best when revealing interesting facts and anecdotes, especially about people. He writes of the men who built billion-dollar lawn conglomerates such as Scotts, ChemLawn, and TruGreen (the latter two are now both owned by ServiceMaster) from small businesses. And there are the many lawn fanatics such as the Floridian who transformed his entire backyard into an exact replica of the 12th hole of the Augusta National Golf Club. And the California billionaire who paid tens of thousands of dollars in fines to water his lawn illegally during a drought year. (His obsession was finally halted by the city when he attempted to have water delivered to his home by tanker truck.)

The author alludes to some of the deeper social and philosophical aspects of the American lawn obsession, though without developing these ideas fully. Steinberg considers Organization Man and his need for lawn control. Yet the lawn is really a symbol of a deeper trend in modern life—the desire to rationalize and standardize everything. Suburbia is the ultimate example of this social experiment: As it represents the standardization of culture, so its lawns amount to the standardization of nature. Like suburbia, the lawn is wholly dependent on big business for chemicals and machines and on big government for cheap water and agronomic research to develop new and better turf.

Steinberg also omits the political dimension of lawn expansion. The lawn grew in tandem with empire. Everything about the lawn is based on the global reach of American power and the spread of markets. Lawn equipment is almost all of Japanese construction, and hand tools are made in China. The majority of lawn-care workers are illegal Hispanic immigrants. Even lawn grass is not American—most varieties were developed in Asia. But the most important global connection of the lawn industry is its dependence on cheap and abundant foreign oil. From the mowers, blowers, weed whackers, and trucks to petrochemical-based fertilizers (all in plastic bags), the lawn industry depends on this resource.

Interestingly, the American South was the last region to capitulate to the lawn cult. Grass was only good if you had livestock to feed. Even today, the South is known for its shabby or nonexistent lawns. Lawns are mowed periodically to keep down the mosquitoes. They are also good places to park your car or clean fish. This makes sense, because the South was the last place to resist empire. But this, too, is changing in the New South, where spacious lawns grace tract mansions and patio homes from Richmond to Houston. The South has arrived, and so have the neoconservatives whose perfect new lawns are slowly replacing the mossy old weed patches of another era.

The American lawn culture is also beginning to change with the end of cheap oil and, especially, cheap water. Many homeowners are opting for less grass or more durable and drought-tolerant varieties. Some are returning their yards to native grasses. Steinberg sees all these trends as good ones that will reduce the environmental and health costs of lawns. One alternative he never discusses, though, is the garden. Home vegetable gardens and orchards were the real losers in the lawn revolution. Most zoning laws today promote lawns over gardens or other types of landscaping. In the past, even city dwellers tended small gardens and often raised chickens, rabbits, and pigeons to provide protein for their diets. Today, keeping a pair of laying hens in your backyard is a crime in most towns, while running a leaf blower at 90 decibels for hours on end is not. The reason is simple. One is an expression of the power of government and industry; the other, of household autonomy.

It is the loss of the rich and varied home garden to the monolithic mass-produced lawn that should concern us most. Local economies died with the rise of American global power, a revolution of which the spread of lawns is a part. The home was transformed into a place of consumption and leisure, rather than of production and work. One way to reverse this trend is to reduce lawn size dramatically and replace lawns entirely with gardens. Wendell Berry once remarked that a quarter-acre of land can provide a family of four with all of its fruits and vegetables, but seldom in America is land put to that use.

A nationwide shift to gardens from lawns would be revolutionary. The recapturing of this economic space would reduce chemical and water use and decrease dependence on foreign oil. It would also entail labor reduction and, hence, slow illegal immigration. The garden and the table are two of the most important Christian symbols. It is time they were reunited and returned to their rightful place in American family life.

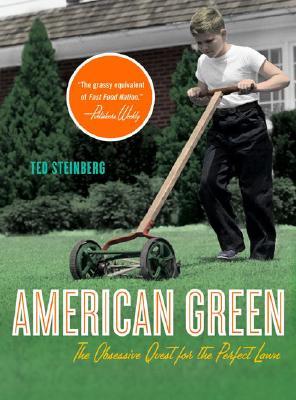

[American Green: The Obsessive Quest for the Perfect Lawn, by Ted Steinberg (New York: W.W. Norton & Co.) 295 pp., $24.95]

Leave a Reply