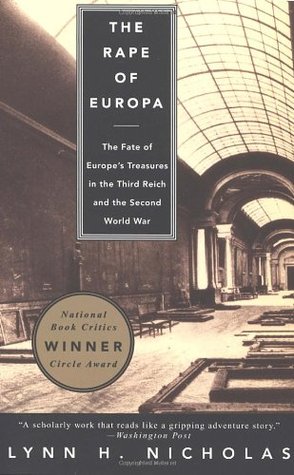

[The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War, by Lynn H. Nicholas (New York: Alfred A.Knopf) 498 pp., $27.50]

Lynn Nicholas has written the most comprehensive account of the Nazis’ attempt to steal, sell, dismantle, and destroy Europe’s artistic heritage, but her stunning illustrations nearly tell the story for her: a picture of 5000 bells that were stolen from across Europe and stockpiled in Hamburg; a photo of the special room for “degenerate” art that Alfred Rosenberg and Hermann Goering established at the Jen de Paume, where Vermeers, Rembrandts, Cezannes, and Renoirs are stacked like Velvet Elvises at the corner gas station; an eery sketch of candle-lit life in the deep cellars of the Hermitage, where relies and masterpieces are protected by half-frozen curators, art historians, poets, and writers. This is a story of preservation as much as pillage, perseverance as much as villainy. The Mona Lisa, Winged Victory, Venus de Milo, and thousands of paintings, sculptures, tapestries, clocks, and stained-glass windows were hurried out of Paris by truck and train shortly before the Germans arrived and hidden in 11 chateaux west of the capital. The National Gallery’s collection was relocated to Wales by underground rail through disused eaves and mines. In our country, the newly opened National Gallery of Art transferred its most important works to the palatial Biltmore estate in Asheville, North Carolina; the Metropolitan Museum used an empty mansion outside of Philadelphia; and “The Declaration of Independence” spent the war in Fort Knox. Nicholas does discuss Allied thefts—such as the infamous ease of WAG officer Katherine Nash, who stole instead of guarded the Hesse crown jewels at Kronberg Castle in April 1945 and who was arrested with her husband in Chicago shortly thereafter—but she does so only briefly and dares not tread on the eristic issue of the Allies’ intentional bombing of Germany’s medieval town squares. (For a tendentious but more thorough account of American looting, see the recently published The Spoils of World War II: The American Military’s Role in Stealing Europe’s Treasures by Kenneth D. Alford.) After the war the Allies—the United States in particular—were left with the daunting task of ascertaining the rightful owners of the thousands of artworks recovered from Germany, a task that continued for decades after the war. The United States did not, for example, return Hungary’s crown jewels until 1977, because of the controversy over returning priceless relics to countries controlled by Russian communists. Many masterpieces, of course, were destroyed or stolen and will never be recovered. Yet as Lynn Nicholas has reminded us, what is staggering is not our losses, but what was courageously preserved.

—Theodore Pappas

[Caring for Creation: An Ecumenical Approach to the Environmental Crisis, by Max Oelschlaeger (New Haven: Yale University Press) 285 pp., $30.00]

Since Professor Oelschlaeger is himself apparently unchurched, the ecumenism referred to in the title of his book is for his own part only opportunism. Indeed Caring for Creation is an appeal to his fellow Greens to harness the energetic superstition of useful idiots, from Roman Catholics to Wiccans, as a means to supplant the secular religion of economic growth that is destroying the planet and to create a broad and deep consensus for an environmentalist agendum. Oelschlaeger claims to have written a confession of sorts, “though not exactly in the tradition of Augustine and other Christians. For most of my adult life I believed, as many environmentalists do, that religion was the primary cause of the ecological crisis. I also assumed that various experts have solutions to the environmental malaise. I was a true believer.” Though still convinced that “religion is deeply implicated in eco-crisis,” he now believes that, “more important, it is involved in any solution.” Since Oelschlaeger refuses to regard any particular faith as “privileged,” he is unable to say what he intends by “religion” but treats all systems of belief with equal indifference. Religion, he says, “is the institution best suited to deal with the ethical and political questions raised by eco-crisis, precisely because it empowers citizens to deal with the questions that elude the bureaucratic mentality.” How might the dominant religious tradition in the West shake free of its notoriously homocentric view of Creation? Well, “Judeo-Christianity” is unique in its ability to reweave itself in the light of changing circumstances without losing its fundamental inspiration.” As, I suppose, the Social Gospel over 1900 dreary years evolved gloriously from the original Four. And “Judeo-Christians” have a powerful incentive to do more “reweaving”: “The reality of ecological crisis has rendered the belief in providence problematic.” Professor Oelschlaeger, however learned he may be in contemporary academic production, is an ignoramus when it comes to Christianity. “The argument that the fall . . . created eco-crisis is . . . helpful. . . . ” he concedes. Of course, it is the crux. “The present world is passing away. . . . ” Has he not heard of the promise of a new heaven and a new earth? Christianity does not put Man above Creation, but the Earth to come above the present one. This is not to say that Christians or other people, even Republicans, are justified in trashing the world we know. Where Oelschlaeger perceives the need to redesign Christianity to respond to the problems of the day, there exists instead the obligation on the part of Christians better to comprehend the teachings of their faith in respect of nature, as the Eastern church has long done. Professor Oelschlaeger has a clue: “Caring for Creation entails only that the faithful look to their faith with new eyes and find therein the words that speak of a loving relationship with and our responsibilities for the Creation.” But if that should happen, we will have no need for environmentalism at all.

—Chilton Williamson, Jr.

Leave a Reply