What a peculiar, in some respects downright weird little world this fascinating biography introduces us to. Imagine a very clever, very plain, very spoiled little boy, born at the turn of the century into the intensely competitive upper-middle or lower-aristocratic class in Britain. Conventional success at sports, diplomacy, the professions, or business being ruled out by physiology and temperament, he makes it his business from his first days at school to entertain his fellows and masters by superior knowingness. Following this policy, he gains a place at Eton as a King’s Scholar. Then, against all prediction, by an unflagging campaign of ingratiation and bedroom politics, he achieves Etonian apotheosis by election to “Pop,” an exclusive society in an exclusive school, peopled by the athletic, the aristocratic, and the beautiful.

From Eton, trailing clouds of glory, he goes to Balliol to read history, again with a distinguished scholarship. Oxford, though, disappoints him. History is hard work, and dons are less impressionable than schoolmasters and schoolboys. So he leaves with a third-class degree, and sets about turning charm and cleverness into a literary career that will supply his needs: money, sex, good food, comfortable surroundings, and the friendship of the rich and powerful—many of whom he’s already met at school, that being one of the emoluments of an upper-class private education.

So far this could be the life story of any aesthete-as-hero in a 20’s novel, but the story Clive Fisher tells is more peculiar, more surprising than that. Cyril Connolly had a capacity for imposing himself not often found either in fiction or real life. For instance: once he discovered the pleasures of hetero- as opposed to homo-sex, a long succession of wealthy and/or pretty young women, undeterred by his frog-like appearance and sponging habits, warmed his bed and attended to his domestic life. He even married three of them (though not the one who changed her name by deed-poll in anticipation of ever-postponed marriage). Appetite, though, always ruled, and not always discriminatingly; one of the more jaw-dropping sentences of the book announces how, at a dinner party later in his life, another guest recognized him as a fellow prowler among London’s homosexual haunts.

His ability to extract large sums of money from publishers and friends was even more remarkable than his sexual history. When he died leaving an overdraft of £27,000 (over $500,000 in post-inflation values), his friends immediately launched a fund to pay it off and take care of his widow. How did Connolly manage this sort of thing? His biographer puts it down to an ability to charm; but the charm cloaked an outlandish degree of selfishness, maintained without diminution to the end. At 23 he not only made his 17-year-old girlfriend pay for his dinner; he ordered the most expensive dishes. When he was on his deathbed, and the Duke of Devonshire, through an intermediary, sent him a present of Muscat grapes from the ducal hothouses, the dying man’s response was, “I wish Andrew would bring the grapes himself.”

Was he then, as the American publisher of this biography announces on the title page, “England’s most controversial literary critic?” He was certainly among the most admired literary columnists of his day—but he seems always to have positioned himself well to the rear of controversy. Although he underwent a predictable but superficial leftist makeover in the 30’s, he was really always a post-90’s aesthete in the fashionable, uppercrust style portrayed (and criticized) by Evelyn Waugh in Brideshead Revisited. In that lifelong role he was undoubtedly a successful consumer of art, a sort of literary Martha Stewart, who lived by publicizing his enthusiasms. As aesthetic pundit, he kept his important friends reassured and instructed, and as reviewer and editor he sold the pleasures of vicarious superiority to thousands of middleclass readers of the Sunday papers.

In his day his prose was much praised. He was a clever parodist, though to my ear his own writing always verges on pastiche, as in his self-consciously “artistic” book, The Unquiet Grave (1944). Sheer self-absorption, in fact, seems to have disqualified him as a creative writer; in the end his only subject was himself, and he was never able to tell the truth about it. His best time came during the war, when anxiety (well-founded) that his chosen way of life might disappear led him to start a periodical. Horizon, intended to preserve it.

Such an essentially comic character inevitably cast amusing shadows on the fiction of his time. There is a touch of Connolly, and of his employment as secretary-companion to the fussy American expatriate, Pearsall Smith, in the character of Anthony Powell’s ambitious young poet, Mark Members. Evelyn Waugh, who nicknamed Connolly “Boots,” and peppered his books with jokes at his expense, drew on him for the character of Everard Spruce in Unconditional Surrender. But then characters like Connolly are recurrent in the history of literature. Dickens portrayed the type once and for all in Harold Skimpole of Bleak House. Sensitive, whimsical, and poetic, Skimpole is too finely tuned to cope with the details of practical reality. Although he insists that he is a child amidst the complexities of the world, he is ruthlessly devoted to his own comfort, and succeeds in persuading the world, in the person of the kindly Mr. Jarndyce, to maintain him in his chosen way of life. Dickens based the character, we are told, on the poet Leigh Hunt, but the type is a perennial, and Clive Fisher has written the biography of Skimpole’s modern avatar. Evelyn Waugh may have liked Connolly, but he saw through him: “a drole old sponge at his best,” he said, “worth six of Quennell.”

This evocatively illustrated, notably well-written, and, in retrospect, hilarious biography is well worth reading. Not only does it open a window onto a character and a social wodd that will seem to many of its readers as fascinatingly remote as the Land of Cockaigne; it also shows, perhaps unintentionally, how an estabhshment based on privilege and competition really works. That is something always worth knowing.

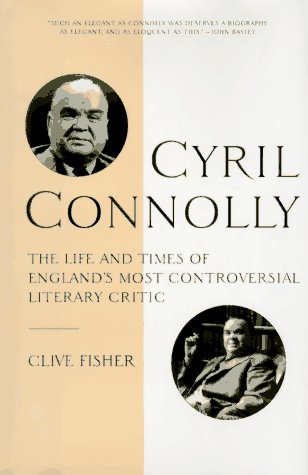

[Cyril Connolly: The Life and Times of England’s Most Controversial Literary Critic, by Clive Fisher (New York: St. Martin’s Press) 466 pp., $27.95]

Leave a Reply