Dr. Bernard Nathanson has written an important book that in time will rank with Merton’s Seven Storey Mountain and Malcolm Muggeridge’s Chronicles of Wasted Time as books which our descendants, familial and spiritual, will examine closely in the 21st and 22nd centuries in order to understand both man’s inhumanity to humanity and to his personal self.

While the book has historical significance, it also possesses importance in the present moment. Bernard Nathanson’s intellectual and moral honesty has enabled many other abortion providers or accomplices, including recently some legislators, to acknowledge their mistakes and join the fight for human life at its most defenseless. Nowhere more clearly than in the United States can one see the divisions lining up behind the forces of the “culture of death” and a “civilization of love.” Dr. Bernard Nathanson’s conversions both to the cause of life and to Christianity (he was received into the Roman Catholic Church by John Cardinal O’Connor on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception in 1996) are indeed highly significant as witness both to the power of scientific evidence and of prayer. It also manifests clearly the inexorable connection between God and the natural law that He has inscribed in human nature.

The basic facts about Dr. Nathanson are well known to many readers. He was cofounder in 1969 of the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws (NARAL, later renamed the National Abortion Rights Action League) and former director of New York City’s Center for Reproductive and Sexual Health, then the largest abortion clinic in the world. In the late 1970’s, he turned against abortion to become a prominent pro-life advocate, authoring Aborting America and producing the seminal pro-life video The Silent Scream. This video was truly revolutionary in its use of the most up-to-date medical technology to depict the horrors of abortion as it actually takes place in the womb of the mother. Along with its successor The Eclipse of Reason, it was widely shown not only on television globally, but directly to legislators in many countries.

During the late 1970’s, Dr. Nathanson became for the cultural anti-life forces in America an object of ridicule and satire in comic strips and news commentary, and the butt of jokes of television comedians. Since then, in addition to his distinguished obstetric medical practice and university teaching, he has given hundreds of lectures throughout the world in defense of the unborn. Now on the verge of retirement, he has written his autobiography, which contains searing personal revelations concerning how a medical doctor could become an abortionist, and also remain open to the possibilities of divine grace.

The first chapter clearly describes the young Nathanson’s relationship with his father, a Jewish Canadian physician, and his family: “We would take long walks together, he and I, and he would fill my ears with poisonous remarks and revanchist resolutions concerning my mother and her family and . . . I remained his weapon, his dummy, until I was almost seventeen years old, when I-as-he rebelled and told him I would no longer function as his robotic surrogate assassin.” Of his sister he writes, “Her mental health destroyed, her physical health intact but—to her befuddled mind—suspect, her children rebellious, fallen in with bad company and truant, my sister killed herself one sunny August morning with an overdose of a powerful sedative.” Regarding himself, “And I? I have three failed marriages and have fathered a son who is sullen, suspicious but brilliant in computer science.”

Religion had no real role in his upbringing. His family was nonobservant, although they did celebrate the Jewish holidays, perhaps as many putative Christians still observe Easter and Christmas, without these Christian solemnities having any real impact on their thought or behavior. Quite striking is his description of his childhood concept of God: “My childhood image of God was, as I reflect on it six decades later, the brooding, majestic, full-bearded figure of Michelangelo’s Moses. He sits slumped on what appears to be His throne, pondering my fate and at the brink of disgorging His inevitably damning judgment. This was my Jewish God: massive, leonine, and forbidding.” This description fits very well with the noted psychologist Paul Vitz’s view that almost all serious atheists are the victims of abusive or absent fathers. At a later period in his life, during a stint in the Air Force, to while away the idle hours he took a Bible study course and “discovered that the New Testament God was a loving, forgiving, incomparably cosseting figure in whom I would seek, and ultimately find, the forgiveness that I have pursued so hopelessly, for so long.”

During his medical studies at McGill University in Canada he had as a professor the famous Jewish psychiatrist Karl Stern, an emigre from Nazi Germany. This relationship would have positive consequences decades later, when Nathanson began to examine more closely the arguments for Christianity:

Stern was the dominant figure in the department: a great teacher; a riveting, even eloquent lecturer in a language not his own; and a brilliant contrarian spewing out original and daring ideas as reliably as Old Faithful. I conceived an epic case of hero-worship of Stern, read my psychiatry with the diligence of a biblical scholar, and in turn was awarded the prize in psychiatry at the end of my fourth year. . . . There was something indefinably serene and certain about him. I did not know then that in 1943, after years of contemplating, reading, and analyzing, he had converted to Roman Catholicism.

Later on Nathanson read Stern’s famous autobiography The Pillar of Fire and realized that the man “possessed a secret I had been searching for all my life, the secret of the peace of Christ.”

In subsequent chapters Nathanson relates a compulsive promiscuity, which resulted in his first encounter with abortion, one performed on his first girlfriend and paid for by his father; the story of his first two marriages; and, in what is perhaps the most shocking and chilling incident in the book, an abortion performed by himself on another of the women with whom he had affairs. But in time Nathanson saw clearly the scientific evidence against abortion, due in great part to new technology which enabled him to see the child in the womb. What he had been aborting by the thousands (he estimates that he was involved, directly or indirectly, in over 75,000 abortions) was in fact a human being from the moment of conception. Consequently, he stopped performing abortions, and became the best-known advocate and convert to the pro-life cause in America.

He ends the book on a note of hope in Christ’s mercy, forgiveness, and offer of salvation. As is often the case in a story of conversion, it is the prayers and personal example of so many of his pro-life friends and coworkers that over time melt down the resistance of a hardened atheistic sinner so that he can see that there might be room in God’s heart even for the likes of him.

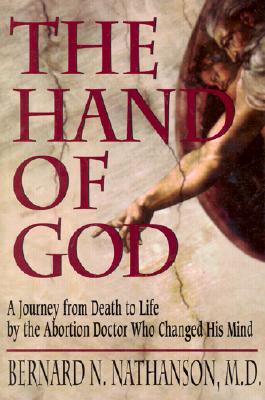

[The Hand of God: A Journey From Death to Life by the Abortion Doctor Who Changed His Mind by Bernard Nathanson (Washington: Regnery Publishing) 206 pp., $24.95]

Leave a Reply