If we wish to understand and profit from a great artist, the essential thing to grasp is his vision, as unfolded in his work. Much less important is something that, unlike the God-given vision, he shares with all of us—his opinions. Still, the opinions of a creative writer with the societal breadth and historical depth of Faulkner not only help us to understand his work better but are of intrinsic interest and significance. Despite his own demurrer, Faulkner is worth knowing as man and citizen as well as writer.

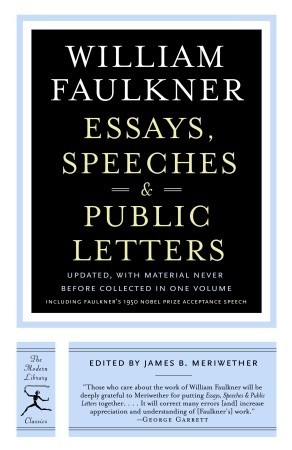

It is safe to say that no one will ever fully understand Faulkner’s work—“where he was coming from,” as they say—who has not studied the public nonfiction writings here collected. Professor Meriwether, the most important Faulkner scholar after the late Cleanth Brooks, presents a work of clear-minded, modest, persevering, and useful scholarship, which is exactly what his title declares it to be. The first (1966) edition contained 39 Faulkner documents. In the revised edition, Meriwether has increased the treasure to 63 items. Here we can find everything from the Nobel Prize address to the (unsigned) inscription on the Lafayette County World War II memorial. Here is Faulkner receiving awards, addressing students, commenting on local and national issues, and discoursing on such topics as the Kentucky Derby, ice hockey, and Japan.

After the early days, Faulkner never wrote reviews and seldom commented on other writers except for special occasions or when questioned by students. He was notoriously averse to Manhattan literary chitchat and networking. What he had to say about literature mostly had to do with the calling of a writer. His view of the rightful duty of a writer, expressed in the Nobel address but also on other occasions, reflected a Christian sense of vocation. The artist’s gift, and the anguish and labor it brings, is justified by service. “The human spirit does not obey physical laws,” and the artist should try “to uplift man’s heart,” to do his unique part in keeping humanity “The Unvanquished.” Needless to say, this understanding did not derive from a Pollyannish (or, to use a more American example, an Horatio Alger-like) conception of human existence. For Faulkner, the unprecedented and undigested fear of nuclear war that marked his time gave the artist’s calling a new urgency.

This reassures us in what we already know to be true, though disputed by self-appointed intellectuals foreign to Faulkner’s context. The protagonist of his fiction is nearly always the human community, simultaneously universal and inescapably particular in place and time. The baseline of man in community, indeed, is what distinguishes Southern literature from “American” literature. The alienated individual, so beloved of writers of the past century, is not for Faulkner a hero but, rather, an object lesson in human failure—like Popeye, Ike McCaslin, or Jason Compson.

It should come as no surprise, though it will to many, that, on the evidence here, it is clear that Faulkner’s politics, like those of most Southerners of his generation, were traditional—those of a Jeffersonian republican. He believed in freedom but also strongly in the necessity of virtue as an effort to keep and deserve freedom. Like other creative people of his generation, he was ill at ease with the American culture of boosterism and self-congratulatory patriotism. (What would he make of the age of Little Bush!) But unlike “American” writers, Faulkner (and other Southerners) did not have to fall back on alienation or Marxism. He had a tradition to invoke, and this surely illuminates his art.

It appears that Faulkner projected a book to be called “The American Dream: What Happened to It?” From some of the speeches and essays herein, we can see what kind of book this would have been. In an address to the Delta Farmers Council in 1952, he suggested that Americans had lost the Founding Fathers’ dedication to “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.” It had once meant not pleasure but the inalienable right to labor for and deserve “peace, dignity, independence and self-respect.” But the American Dream had devolved into “a vision of ease and plenty” in a society suffused with “a universal will to regimentation.”

In 1947, protesting in the local paper some bureaucratic desecrations of Oxford architecture, Faulkner wrote: “They call this progress, but they don’t say where it is going.” In a 1955 Harper’s essay, “On Privacy” (subtitled “The American Dream: What Happened to It?”), he observed that the American dream of freedom and equality had been debased by a pervasive failure of “taste and responsibility.” In the same year, describing for Sports Illustrated his first view of a hockey match, Faulkner wrote:

Only he (the innocent) did wonder just what a professional hockey-match, whose purpose is to make a decent and reasonable profit for its owners, had to do with our National Anthem. What are we afraid of? Is it our national character of which we are so in doubt, so fearful that it might not hold up in the clutch, that we . . . dare not open a professional athletic contest or a beauty-pageant or a real-estate auction [without a rendition of it]. . . . Or, by blaring and chanting it at ourselves every time . . . do we hope to so dull and eviscerate the words and tune with repetition, that when we do hear it we will not be disturbed from that dreamlike state in which “honor” is a break and “truth” an angle?

Judging from his numerous letters to newspapers, Faulkner, in his last years, like every other thoughtful Southerner, was unable to avoid preoccupation with the fact of his region having become the target of relentless national crusading and the reconstructionist itch. His wrestles with the situation do not reveal a pattern pleasing to 21st-century tastes, or indeed much of any pattern at all. The situation was fluid, and Faulkner died in 1962 before the full trajectory of the civil-rights revolution could be discerned by anyone. But his writings do reveal some fundamental assumptions that illuminate the context and allow us to predict his likely reaction to future events. The truth which follows is, like much else, conveniently suppressed in the official and self-congratulatory history of civil rights: In Faulkner’s lifetime, the race question was seen entirely as a matter of a righteous America applying the rod to an un-American South. There was not a glimmer of recognition in the national discourse—political, scholarly, or journalistic—that there was any other aspect to the race question. It took the first Watts riots, the movement of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s crusade to the North, and George Wallace’s successes with Northern voters to shake the masters of American society into the admission that race relations were a national, and not merely a Southern, problem.

Faulkner was writing before the admission came. He was a Southerner living with the intense criticism and hostile action of outsiders. Like most other Southerners, he did not buy into the mythology of the outsiders’ disinterested benevolence and wise understanding of what they were about. He sensed, for instance, that the zeal for blaming Dixie for all the nation’s evils had something to do with fear—the Northern fear of the dangers they had created in the centers of their own cities. (Official American history, of course, still blames the pathologies of the Northern cities on the Old South, which ended long ago and far away.) Faulkner suffered no illusions either about the raw difficulties besetting the path to equality.

But in spite of all, William Faulkner—as human, citizen, and writer—discovered a substantial truth. His lesson and his hope were that his fellow Southerners would be guided by what they themselves knew to be just. In this, he was prophetic: Blacks and whites in the South have accommodated themselves to astounding changes relatively peacefully, with good will and good manners—while, or so it seems from the vantage point of South Carolina, hatred and strife have been steadily on the rise in more enlightened parts of the Union. The potential for Christian charity and fellowship that Faulkner invoked, at a time when it was nearly invisible to others, has much to do with this.

[Essays, Speeches & Public Letters, by William Faulkner, edited by James B. Meriwether (New York: The Modern Library) 352 pp., $13.95]

Leave a Reply