Late in October 1899, in the town of Deming, New Mexico Territory, the commander of Scarborough’s Rangers recognized a face familiar to him from the pages of Cosmopolitan magazine, one of many publications then devoting considerable media attention to the Bandit Queen, a youngish woman from Chicago. In the company of another small-time crook, she had held up a stagecoach near Globe over in Arizona the previous May and robbed the passengers of $400. George Scarborough traced Pearl Hart and her companion, one Ed Sherwood in whose company she broke jail in Tucson, to a sordid hotel room where, surprising them in the altogether, he arrested the couple. Pearl’s clothes being out to the Chinese laundry, Scarborough returned her to Tucson in men’s dress—the disguise in which she had robbed the stagecoach as well as, in Miss Coleman’s treatment of the story, ridden West from Chicago in a boxcar with a rail hobo named Joe Boot, later her accomplice in the Globe stage incident.

The story of Pearl Hart offers wonderful material for the competent writer, and Miss Coleman has turned it to full advantage in I, Pearl Hart, a Western Sister Carrie of sorts. Stage robbery aside. Pearl is probably best known for Scarborough’s later assessment of her: she was, he said, one of the foulest-mouthed persons (not “women”!) he had ever listened to. Yet Pearl’s vocabulary was by no means restricted to blasphemies and four-letter words. As the daughter of a respectable civil engineer, raised in a Catholic family and educated by nuns at a Catholic school in Chicago, she was a highly literate and—when necessary articulate woman of no inconsiderable resources, as well as of cunning.

While the “memoirs” on which the novel is based are scanty to the point of nonexistence, Coleman has carefully researched what is known, and knowable, of her subject’s life. Pearl Hart, who died in 1957 in her middle 80’s, was notoriously reticent about her history; people acquainted with her in the years following her second marriage to a mining engineer, when the couple was living first in Cananea, Mexico, and later in Arizona, recalled a quiet woman rocking silently on her front porch while she smoked cigarettes. Her descendants, though agreeing to be interviewed by Miss Coleman, requested that she employ a pseudonym in place of her second husband’s family name. No one knows how Pearl escaped from the Yuma Penitentiary in Arizona Territory, where she served time as the prison’s first woman prisoner, and so the author has felt compelled to offer a fictional scenario of her own devising.

I, Pearl Hart is to some extent the story of a legend rather than of an historical figure, and yet the legend, in Miss Coleman’s hands, is as much or more a novelistic creation as it is an historical one, a period piece. Yet the period is substantially recreated, and so is the place. Partly because Arizona, in its natural as opposed to its human aspect, has not changed that much in the last century, and partly because Miss Coleman (an Easterner from Pennsylvania, now resident in the lovely southeastern corner of the Grand Canyon State) has deep sympathy and an observing eye for the Southwestern landscape, the setting of her book is made present for the reader.

Pearl Hart came West from Chicago in flight from her first husband, Frank Hart, a professional gambler and compulsive wife-beater. Today the Old West is admired by conservative-minded people appreciative of a time and place in which men were men and women were women. In reality fact is more complicated than myth. The frontier was a region in which adventurous and optimistic empire builders worked to recreate the civilization of the East by asserting and establishing conventional social values and customs. It was also a draw not just for simple outlaws but for social ones as well—unconstrained souls with what today would be described as countercultural inclinations in search of elbow room and a greater social relaxation. Pearl Hart, the Bandit Queen, belonged to the second category of outlaw much more than she did to the first. Miss Coleman’s portrait of her shows a somewhat self-pitying, at times even self-dramatizing, victim, a forerunner of the stereotypical Battered Wife of modern times. Abused though she certainly was, spousal violence seems to have been a further impetus to Pearl’s outspoken feminism rather than the fundamental cause of it.

Coleman’s Pearl Hart is a woman impatient not just of A Woman’s Place in Society but of society itself: an adventurer whose restlessness was determined not by the condition of her sex but by impulses basic to her character. On trial for her role in the Globe holdup, she delivers an impassioned address to the jury: “Think about me, separated from my children. Think about the fairness of your laws. Women sent to jail for adultery while men go free. Women blamed for the fact that their husbands beat them. Women who abandon their children because they can’t care for them. This is justice?” She is acquitted, only to be rearrested immediately afterward on the separate charge of stealing the stage driver’s .45 pistol and sentenced to five years at Yuma.

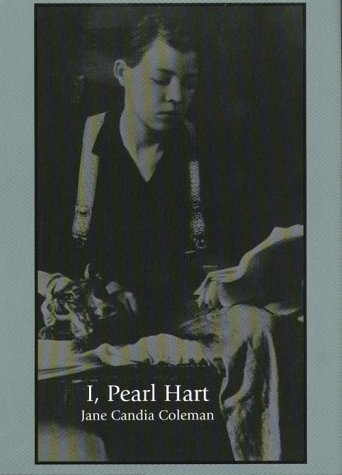

The jacket photo shows a pretty young woman with short hair and a full (rather than foul) mouth, slender; wearing pants held up by embroidered suspenders over an open-necked shirt and reading a newspaper as she fondles what appears to be a bobcat (but is probably only a fierce tabby) at her side. The charm of Miss Coleman’s Pearl Hart is not that of an early Betty Friedan but of one of those originals who pioneered the American frontier, as well as the less attractive, less interesting, and far more restrictive American future, in search of the space and openness that until recently at any rate have always spelled freedom for the American people.

[I, Pearl Hart: A Western Story, by Jane Candia (Coleman Unity, Maine: Five Star) 222 pp., $18.95]

Leave a Reply