Of the four major North American deserts, the Mojave has been, at least until recently, the least explored. Good parts of the Sonoran Desert are more forbidding; most of the Great Basin Desert lies farther from highways and settlements; and much of the Chihuahuan Desert is less interesting than the fiercely hot Mojave of California and western Nevada. Still, accidents of geography and climate have left the relatively accessible Mojave the province of desert rats, isolated Indian nations, prospectors, and outlaws. All that is changing, writes David Darlington in his thorough history of The Mojave, an account populated by six-foot-tall, club-wielding Indians, by frustrated engineers trying to build ocean-going canals in the desert, by bureaucrats assuring “downwinders” that A-bomb blasts were nothing but minor inconveniences, by madmen seeking sanctuary in the American outback.

To the untrained eye, Darlington writes, “the desert is evil.” He elaborates: “It is deadly and barren and lonely and foreboding and oppressive and godforsaken. Its silence and emptiness breed madness. Its plant forms are strangely twisted, as are its citizens, who live there because they can’t get along anywhere else.” This is hyperbole, of course, but it explains, or so Darlington suggests, why the federal government should have chosen deserts, those geologically and climactically volatile places, to store toxic wastes and explode nuclear warheads (“because there’s nothing out there to damage”).

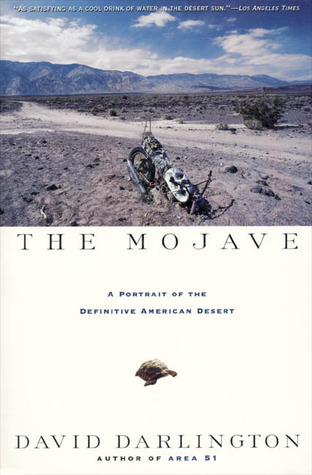

On cursory inspection, there seems indeed to be little damage to the Mojave, the realm of “the Joshua tree, the desert tortoise, the high-speed jet fighter, and the car.” (The desert’s unofficial symbol, Darlington notes, is the abandoned vehicle.) But, he adds, there is surprisingly abundant animal and plant life even in the most barren parts of the Mojave. Although natural history is not foremost among Darlington’s interests, he well explains the ecological workings of the Mojave, distinguishing it from neighboring biomes in a long account of the life history of Gopherus agassizi, the desert tortoise.

But human history interests Darlington more, especially the personal histories of the people who live now—quietly, for the most part—in the Mojave, selling gas and sodas to passersby, milling gravel and ore, prospecting, and especially ranching. The economy of cattle grazing is a matter of vital importance and of fierce debate in the contemporary West. In the Mojave, as in other deserts, the argument takes on added force because overgrazing is a demonstrable cause of environmental degradation from which recovery is a slow process. While recognizing this, Darlington is careful to let the people who earn their living by ranching have their point of view.

Indeed, Mojave is at its best when it allows the people of the desert to speak their minds, lending a perspective that we might otherwise not have. Many writers have made their coin writing of the Mojave-haunting Manson family, of which there are reported to be more members now than in the late 1960’s, but the threat of the dune-buggy psychos takes on a different color when seen through the vantage of desert rat Tom Ganner, who remarks, “We’ve had Manson people pass through here, but they’re really more of a pain in the ass than anything else.”

Darlington also understands, as too many environmental writers do not, that many people live and work in the difficult places that lie far from policymakers’ air-conditioned offices. He is thus ambivalent about the kinds of federal protection being considered for the Mojave. “As a rule,” he writes, “I’m all for wilderness, but it seemed that the area’s ungoverned mystique would surely evaporate if it became part of a national park.” The people of the desert are, he writes, near uniformly opposed to falling under the protectorate of the National Park Service, in part because “the desert has historically occupied the most antiregulatory place in the American imagination,” its residents men and women who usually want nothing more than to be left alone. The 104th Congress seems to be letting them have their way; in 1995, the House Interior Appropriations Committee awarded the Park Service the sum of one dollar to manage roughly nine million acres of desert.

Neither is he happy, however, with the current trend toward development. Las Vegas, the Mojave’s most populated settlement, is an example of how not to make cities in the desert; so are the newly sprawling ranchettes of Antelope Valley just over the mountains from Los Angeles.

While the names of new communities in Antelope Valley aspired to evoke the outskirts of Paris or London, their counterparts in the Nevada desert . . . suggested an ecosystem in imminent danger of drowning. Among Clark County’s new housing projects were the Lakes, Green Valley, Silver Springs, Sunset Bay, Desert Shores, Bay Breeze, and Bermuda Springs. In an effort at consistency, developers matched these names with moisture- intensive landscaping, specifying sod lawns and shade trees for yards in a region with 20 percent relative humidity and four inches of annual rainfall.

The result, in Las Vegas, is a scandalous rate of per capita water use: 250 gallons a day, far higher than New York’s. But development is everywhere in the Mojave, and development seems to be the desert’s future. West of the hamlet of Gorman in the Tehachapi Mountains lies the densest stand of Joshua trees—one of The Mojave’s characteristic plants—in the world; this is also precisely where developers are working busily to turn the Mojave Desert into a bedroom community of Los Angeles stretching from San Bernadino to the Colorado River, swallowing little towns like Baker and Soda Lake and Rhyolite into the urban maw.

Given a choice, Darlington rightly suggests, we are better to see cattle ranchers and offroad racers, perhaps the occasional psychopath, even federal managers, than endless strip malls and condominiums in the Mojave Desert. His book is a reasoned plea for according respect, environmental and cultural, to a place long regarded as a wasteland, but one that is now being torn apart.

[The Mojave, by David Darlington (New York: Henry Holt) 337 pp., $25.00]

Leave a Reply