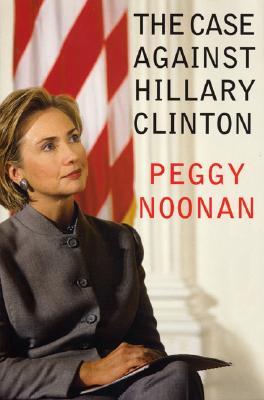

The Case Against Hillary Clinton is a strange book. It would be less strange if it were titled Peggy Noonan’s Psychoanalyses, Future Speculations, and General Meanderings, Which Are All Well-Written and Witty. But a book billed as an indictment of the First Lady, written by none other than Ronald Reagan’s most lauded speechwriter, creates certain expectations.

One expectation is that conservatives, right-wingers, and anyone else who already dislikes and distrusts Hillary Clinton and her agenda will naturally whoop and cheer as they turn the pages. Another expectation is that Noonan would at least try to present the charges against Mrs. Clinton in such a way as to keep Hillary sympathizers from dismissing her as just another Clinton hater before she even presents her case.

But Noonan starts off with an imaginary scene set in the future, with Hillary about to give her acceptance speech after winning the New York Senate race against Mayor Rudy Giuliani (update that to Rick Lazio). Noonan describes the First Lady’s manner of dress, the roaring crowds, and Hillary’s thoughts—a multifaceted barrage of “Hah, I showed them!” attitude and utter self-indulgence. It seems real. You can just picture it. You just know the First Lady’s thoughts would indeed be as puny as the ones so well described by Noonan—if you already are a Hillary foe. But for anyone on the undecided list, there is no reason to view this very funny concoction as anything more than entertainment á la Saturday Night Live—nor to take any of Noonan’s subsequent criticisms seriously. If Noonan hoped to do more than preach to the choir, she blew it in her preface. (One suspects she is a bit too enamored of her own talent and wit to resist showing off before making an actual case.)

This ingenuity provides the high point of the book, a fictional 15-page address by Mrs. Clinton to Steven Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg, Ted Turner, et al., the who’s who of the entertainment industry. Her speech is about the cultural morass of death, sexual license, and deviance by which American children are surrounded. It is so all-consuming that parents can’t simply “change the channel if they don’t like it” because another channel will have more of the same. This fictional Hillary has found a real voice and true guts. She presents the gathered Hollywood might)’ with a chance to do the right thing for the sake of doing good: Make funny, quality entertainment that celebrates the goodness in people, not their dark sides; realize that just because First Amendment rights protect any expression, no matter how useless and vile, not all artistic expression must be useless and vile.

The speech dazzles with its cleverness. These 15 pages alone are worth the price of the book. It is Peggy Noonan at her best because it’s a speech, and writing effective speeches is what Noonan does best. The speech brings to mind the woman who, after the Challenger explosion, quoted poetry to describe how the astronauts will “touch the face of God,” giving President Reagan one of his greatest lines.

But the fact of the matter is that this wonderful speech is not a ease against Hillary Clinton. It is about what Hillary could have said, and didn’t; but while both Clintons could have used their positions to do good, the missed opportunity of persuading media moguls to stop producing smut isn’t exactly a damning indictment. And not taking positive action is hardly a trait unique to the Clintons.

Other building blocks of the case against Hillary include dead-on projections of what her Senate race against Giuliani would have looked like (no smoking gun there); a seven-page speculation of what thoughts might pass through Hillary’s mind during idle time on an airplane (including amusing but gratuitous insults of Al and Tipper Gore); and Noonan’s 14-page plea to her childhood girlfriend not to vote for Mrs. Clinton. This is Noonan at her worst. Trying to expose the hollowness of Hillary’s claims that she “shares the concerns” of New York housewives, Noonan veers off into class warfare, blasting Mrs. Clinton for a privileged lifestyle. The attack is so cheap that it could cause even card-carrying members of the “vast right-wing conspiracy” to feel the First Lady’s pain.

The Case Against Hillary Clinton is as much about the President as it is about the First Lady, since, as Mr. Clinton has (in)famously said, “you get two for the price of one.” Noonan gives a good account of the essence of the couple’s “Clintonism”—their soulless power grabbing, manifested in the countless scandals and “snafus” of their seven-year reign. “We can stop it here, in the battle of New York,” she proclaims at the book’s end.

You will decide it. Either they will continue to deform and lower our national politics, or they will not. It is up to the people of New York. And that is the great thing about democracy: Before Hillary Clinton gets to decide your future, you get to decide hers.

This is good stuff; but it is too little, too late. During a recent TV interview with Judith Regan, Noonan proclaimed that she intended her book to “have the urgency of a pamphlet.” It would have been more urgent had it been a pamphlet. The failure of Noonan’s case against Hillary Clinton is not that she doesn’t make it—she illustrates the myriad shady dealings and lies in which the First Lady has been so intimately involved—but that she almost completely negates a case so easily made well through her overdose of speculation, hearsay, and fantasy. It does not help that nearly half her sentences begin with “I believe,” “I think,” or “It seems.”

Noonan’s book ranges from fun to touching to weird. Serious, it is not. And it won’t send even the mildest of Hillary sympathizers screaming in the opposite direction. What a shame; what a missed opportunity.

[The Case Against Hillary Clinton, by Peggy Noonan (New York: Regan Books/HarperCollins) 181 pp., $24.00]

Leave a Reply