by Jason L. Riley

Basic Books

304 pp., $30

It is hardly surprising that an economist and historian of ideas who spent a long career arguing against the conventional wisdom of politicians and policy wonks would have a biography about him titled Maverick. It is much more surprising that the same man inspires the lyrics of Eric July, front man for the rap-metal group BackWordz, and that, despite no social media presence, he has 833,000 followers on a Twitter page dedicated solely to quotes from his writings. These are exciting phenomena for a man who is, by his own description, boring.

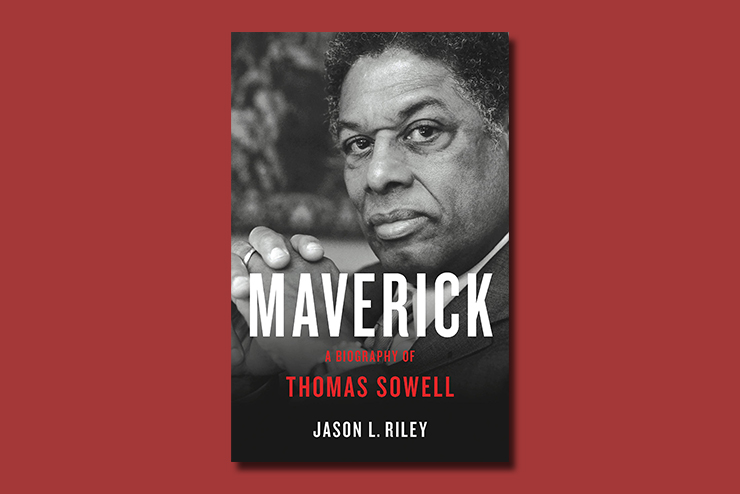

Wall Street Journal columnist Jason Riley’s biography of Thomas Sowell reveals more about the mind than the man, but that is precisely where the excitement lies. And judging by the response to Riley’s companion documentary, Thomas Sowell: Common Sense in a Senseless World, which boasts nearly 4 million views on YouTube, people are hungry for more.

Not that you would know by reading The New York Times. The newspaper—for all its obsession with race, social justice, and diversity—stopped reviewing Sowell’s books 20 years ago, which was around the time it also stopped resembling anything like a legitimate newspaper.

Despite Sowell’s retiring from writing his syndicated column in 2016, the force and clarity of his mind have continued to propel him into media platforms that will make him all but impossible to ignore for generations to come.

Riley’s book is primarily concerned with Sowell’s intellectual development from a boy who did not know what a library was to an astonishingly prolific career in academia and research at prestigious institutions across the country. Sowell’s personal life, as told in his memoir, A Personal Odyssey, and in the subsequent collection, A Man of Letters, does make interesting reading. Riley puts both to good use in sketching the outline of Sowell’s life.

Sowell spent his early years in Charlotte, North Carolina. His childhood home did not have electricity, central heating, or even hot running water. He remembers those years as some of the happiest in his life, never realizing that he was poor. At age nine, he moved with his family to Harlem. It was a culture shock, but he found solace in reading and study. A friend took him to a library, a place he had “never been before and knew nothing about,” and it was then that he “developed the habit of reading books.”

Despite a tumultuous family life, Sowell did well in junior high and went on to attend Stuyvesant High School. But he ultimately felt compelled to leave home, and he lived in a homeless shelter until he found enough work to afford a place of his own. He served in the Marine Corps during the Korean War, and after a successful stint at Howard University, Sowell obtained degrees from Harvard and Columbia. Along the way, he demonstrated the freedom and independence that would define his career.

Sowell chose the doctoral program at the University of Chicago so that he might study under Nobel laureate economist George Stigler. He distinguished himself and, despite being a Marxist, thoroughly embraced the methodology of the Chicago School. Both Stigler and Milton Friedman recognized Sowell’s brilliance and arranged for him to receive a prestigious Earhart Foundation grant (nine Nobel Laureates have been Earhart fellows). The renowned economists admitted to the Foundation’s trustees that Sowell was a socialist but that he was “too smart to remain one for too long.” They were right.

Sowell’s reading and research—and his relentless pursuit of the facts—led him to question socialist assumptions and theories. He was finally cured of his Marxist sympathies after “seeing government at work” during an internship at the Department of Labor.

After completing his doctorate at Chicago, academic posts at prestigious schools followed: Cornell, Amherst, and UCLA. Critical of student protests at Cornell in the 1960s, he refused to embrace the racial rhetoric of black nationalism movements. Sowell also argued against lowering academic standards to increase student diversity and eventually left Cornell rather than be forced to do so.

The experience undoubtedly contributed to his later observation that the “academic world is the natural habitat of half-baked ideas.” Not one to suffer fools gladly or indefinitely, Sowell eventually left academia altogether and since 1980 has served as a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution.

His output is astonishing. He has lectured widely, churned out dozens of books, and written a syndicated newspaper column. Sowell’s clarity and concision earned him a large following in the popular press, where eager students of all ages read and debate his work. This is how Basic Economics became—and remains—his best seller. As one who finds anything faintly whiffing of economics a wretched bore, I can say that Sowell—more than Friedman or Friedrich Hayek or Adam Smith—made a devoted student of me. And, perhaps most surprisingly, his scholarship never suffered by catering to a popular audience.

Sowell’s economic scholarship was praised by Friedman and Stigler, but also by Hayek, who lauded Sowell’s brilliant expansion in Knowledge and Decisions of his concepts about bureaucratic decision-making. The wide dissemination of information and decentralized control advocated by Hayek and Sowell ran counter to the prevailing trend among 20th-century economists and policy makers who favored planned economies. It also revealed a different concern of Sowell’s beyond the stifling air of economics: the rise of an intellectual elite and their increased influence over public policy as direct threats to freedom. A prescient concern, it turns out, given the recent inanities of Dr. Anthony Fauci’s NIAID and of the CDC.

Sowell has consistently criticized public policy researchers, politicians, and bureaucrats for ignoring the methodological axiom that correlation is not causation. It opens the door for ideologically-driven conclusions that mollify a certain special interest group politically but yield damaging consequences. Such political solutions, he says, “serve the political leadership well, even if they are counterproductive for the racial or ethnic group in whose name they speak.”

An obvious example is the debate surrounding race and economic inequality. Sowell, relying on statistical evidence, argues that the declining black poverty rate prior to the 1970s demonstrated that it wasn’t preferential programs and government billions that raised the economic status of blacks. Racial entitlements, he observes, have harmed blacks by convincing them that they cannot achieve upward mobility without government help. Many black intellectuals have perpetuated this perception, as they have “a very large, vested interest in certain beliefs, which underlie various programs from which they benefit enormously.”

This thought of Sowell’s is a recurring theme in Riley’s own writing, as he relies on much the same evidence to make potent arguments in his excellent book, Please Stop Helping Us: How Liberals Make it Harder for Blacks to Succeed, as well as in his newspaper column. In Maverick, as in other media forms, Riley does the heavy lifting of keeping Sowell’s work at the heart of contentious debates on race, economics, and culture. It is an important work of conservation for future generations, especially as Sowell approaches age 92.

Still, doubters and haters abound. Sowell’s quest has been called “quixotic”; he “denigrates” black Americans; he resorts to “pointing fingers”; he is in “a rush to draw conclusions”; he is labeled an “Uncle Tom.” Political scientist Alan Wolfe accused him of being “simply depressing,” a most egregious intellectual sin apparently. “Perhaps Sowell’s joylessness stems from the fact that his main idea is the hatred of ideas,” Wolfe speculates in The New Republic. Setting aside the stupidity of this claim, Wolfe demonstrates what much of the criticism of Sowell is: weak and whiny. Academic journal articles that at least pretend to wrestle with Sowell’s ideas are conclusory and laden with jargon.

Riley describes Sowell’s philosophical conservatism as being in the classical liberal vein combined with Chicago School methods. His black conservatism is not a blind conservation of all things past—Jim Crow laws, racial preferences—but a conservation of the great tradition of self-reliance in black history. Booker T. Washington and Frederick Douglass are obvious examples.

There is continuity with this tradition in Sowell’s work, but his method is far more rigorous and, as such, cannot be dismissed lightly. For all his scholarly rigor, though, Sowell is a master of cutting concision. “I sometimes wonder,” he muses, “if those of us who are black ought not to consider declaring some sort of moral amnesty for guilty whites, just so that they won’t keep on saying and doing damn fool things that create additional problems.”

Thomas Sowell is first and foremost an economist. But thankfully for his students and readers, he has brought his analytical mind and infectious wit to bear on many of the challenges we face in this country. He does not retreat from confusion or contention and, unlike many public intellectuals, goes where evidence—not ideology—leads. Riley’s aptly titled book is a superb introduction to Sowell’s life and work.

Leave a Reply