There are two—equally indispensable—Paul Fussells: one is the erudite professor of English (at the University of Pennsylvania) who is the author of such brilliant studies as The Great War and Modern Memory; the other is the scalding critic of American pretension who writes such astute books as Class: A Guide Through the American Status System. Either one is worthy of our closest attention, and it happens that the latter is on display in this latest work, which is an alphabetized search-and-destroy mission over the vulgar terrain of American culture and mores.

BAD—as distinguished from merely bad, which has always been with us—is a (late) 20th-century phenomenon. “To achieve real BAD,” writes Mr. Fussell, “you have to have the widest possible gap between what is said about a thing and what the thing actually is, as experienced by bright, disinterested, and modest people.” Needless to say, America offers a cornucopia of possibilities to illustrate this theme, and Mr. Fussell covers the most egregious available.

To be sure, the targets of Mr. Fussell’s vituperation are not new, but his wit and aesthetic perspicacity are rare indeed. For example, in his analysis of BAD architecture, he says, “Architecture, the most visible and unignorable human performance, is the place where people most publicly derive their understanding of themselves, and contemporary Americans have great trouble achieving that frank, unshowy Swiftian simplicity. . . . Straight lines, inevitable in the steel, aluminum, and glass boxes which now pass for buildings, are death to the imagination.” Mr. Fussell has clearly hit the mark:

Equality is one of the ideas glorified by the new architecture, and that might be a good thing, but this equality is the equality of ignorance, a celebration of the assumption that no one has sufficient experience or learning to enjoy the allusive exercise required by traditional architectural details like balustrades, crockets, finials, metopes, or triglyphs. The current architecture implicitly patronizes its users and audiences.

BAD has worked its way into virtually all the interstices of American life: the atrocious condition of deregulated airlines, engineering that is designed so poorly that it benefits only plaintiffs’ lawyers when it inevitably collapses, and, of course, language. The flight from simplicity and clarity in the use of language is a manifestation of class anxiety. Mr. Fussell observes, “Pretentiousness and euphemism are . . . the stigmata of verbal BAD”: thus, rain becomes “shower activity,” a pen becomes a “writing instrument.” Curiously, however, Mr. Fussell neglects to mention the wretched jargon that emanates from the academy. This omission is something of a surprise, for Mr. Fussell is one of the few academicians still writing in English, and surely he must take offense at the work of his colleagues.

In his penultimate chapter, “The Dumbing of America,” Mr. Fussell sees dumbness rampant, reaching even into the professions. “[I]t’s now no surprise,” he notes, “to hear a partner in a law firm complain that the products of even the best law schools he interviews can’t speak or write articulately, let alone eloquently—these are young people unable in today’s TV and visual atmosphere to perceive that the law is about little more than language precisely construed and effectively deployed.” In fact, to read a legal brief or trial manuscript often means enduring a deluge of malapropisms, bungled cliches, and pure vapor.

Mr. Fussell attributes a large part of our dumbing to television and “the collapse of the public secondary school.” (“When was a truant officer last seen?” he wonders.) Moreover, much more is at stake—as many thoughtful people intuit—than the mere decline in American economic life. “Even admitting some disagreement about the precise reasons, one thing is clear: a minor cost of the dumbing is the transfer of American economic power to Japan. A major cost is the wiping-out of the amenity and nuance and complexity and charm that makes a country worth living in.”

Mr. Fussell’s assault on American BAD is broad, but it is slightly disappointing that he spends so much time. excoriating the more popular aspects of culture. In his analysis of BAD magazines, for instance, Mr. Fussell is rightly harsh in his view toward such publications as Connoisseur and Architectural Digest. But what about the pretensions and unreadability of various intellectual journals? If BAD has a home, it most surely is found in a great deal of the nonsense that passes for literary and cultural criticism these days.

Mr. Fussell is entitled to select his subject and its scope, and to argue with that selection is to quibble. If you are looking for a robust jeremiad to read, say, on a plane into which you have been crammed (a product, says Mr. Fussell, of “the rapid proletarianizahon of air travel after the Second World War”), peruse BAD. You will then realize that your disgust at the condition of your country has been properly cultivated.

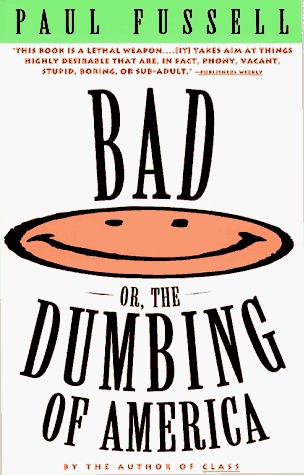

[BAD: Or, the Dumbing of America, by Paul Fussell (New York: Summit Books) 201 pp., $19.00]

Leave a Reply