In November 1972 I voted for the re-election of President Nixon. Granted, it was only an elementary-school straw poll, but I was still thrilled when he carried the student body by a three-to-one margin. On election night, the electoral map was covered in a sea of blue (in those days each party retained its appropriate symbolic color), and in my naiveté I believed that the country had righted itself after the disorder and perversity of the 60’s.

Nixon’s landslide was the product of his New Majority, born in 1968. Nixon and his chief advisors, including a young Pat Buchanan, realized that the Democratic Party’s lunge to the left had created an opportunity to peel off entire blocks of traditional Democratic voters: white Southerners, blue-collar workers, Northern ethnic Catholics. Nixon’s 43 percent of the national popular vote in 1968 was only a plurality, but add Wallace voters to the mix, and the election amounted to an antiliberal landslide (57 percent). Four years later, Nixon won 61 percent of the popular vote and carried 49 states. Over the next three decades, his new majority delivered four presidential victories out of five (three of them landslides), a Republican Senate in 1980, and, in 1994, a Republican House for the first time since 1952.

For a while, it looked as if the Democrats would not win another presidential election. Republicans could count on winning—virtually every time—the whole of the South, the lower Midwest, upper New England, the Great Plains, the Rocky Mountains, the West Coast, and Alaska. How could they ever lose again?

Yet since 1992, the Republicans have won only two out of six presidential elections, both of them narrowly, and one of them dubiously. Now it looks as if it is the Democrats who cannot lose. What happened?

To understand what went wrong, we must first understand what went right, and to do that we have no better guide than Patrick J. Buchanan. Buchanan’s career has oscillated between journalism and politics: editorial writer, advisor to presidents (Nixon and Reagan), columnist, cable-news commentator, presidential candidate (three times), and author. Yet unlike others who have gone round and round through the revolving door, Buchanan has never been a party hack, never a paid liar, never a weathervane for the fashionable wind. Rather, he has been something of a Cassandra. It is no coincidence that the two presidents he served won all four of their elections, and that the two Republicans he challenged in the primaries (one an incumbent president) both lost the national election.

Despite the Reagan interlude, the Republicans have never really ceased to be the party of Wendell Willkie, John Dewey, Nelson Rockefeller, George Romney, Bob Dole, and the Bush family—that is, the party of globalism, free trade, corporate welfare, high finance, open borders, and fashionable leftism. Antigovernment rhetoric, phony religiosity, and Southern accents aside, they have not changed.

Buchanan knows this very well. He has written more than one book on the subject, and his insurgent campaigns of 1992 and 1996 were intended, at least in part, to expose the con and to flush the corporatists out of the bushes. In large part it has worked. Every Republican candidate since George H.W. Bush has spent much of his campaign attacking the Republican base for being too conservative and affirming his support for elitist policies. Since independent voters and disaffected Democrats are more populist than conservative, the effect has been to drive such voters away, hence the collapse of the Nixon/Reagan coalition. In seeking to rationalize their repeated failure to win the presidency, the Republican establishment, along with the Democratic Party and the punditry, have blamed the nativism of Republican voters. If only they would stop being so anti-immigrant, their leaders could pass “comprehensive immigration reform” (a.k.a. amnesty), and millions of hard-working, family-values Hispanics would flock into the Republican ranks, their natural home.

If prominent Republicans really believe this, they are even more stupid than traditional conservatives previously thought. That Democrats and left-leaning journalists are so solicitous of the political health of the Republican Party that they would give it sound advice on how to raise its share of the vote raises certain suspicions that perhaps they know that such a policy would not really benefit the GOP. Hispanics are not going to shift their partisan loyalties because the Republicans finally cave on amnesty. Rather, they will see it as proof of their own growing power. Hispanics dislike the GOP primarily because they see it as the party of white America, a group they resent and hope to dispossess. Incessant pandering may win a few votes, but nothing more.

In 1966 Buchanan, after he joined Nixon’s staff (where he was known within as “Mr. Conservative”), had to contend with an earlier form of the Hispanic strategy, the belief that Jews and middle-class blacks were ready to bolt to the GOP if only they were courted to do so. Buchanan pointed out that these two groups made up a very small portion of the electorate, that they were not ready to change parties, and that the attempt to win them over would confuse the much larger number of disaffected whites who were ready to leave the Democratic Party but had to have a reason to vote Republican. Buchanan was supported by a young Kevin Phillips, who understood that politics is a zero-sum game; that courting one group would send a signal to other groups that you are not really on their side. “The whole secret of [American] politics,” Phillips told Garry Wills, was “knowing who hates who” (sic). Besides, “who needs Manhattan when we can get the electoral votes of eleven Southern States?” Democrats and journalists may tut-tut at such Machiavellian calculations, yet they make them too, perhaps more so; what is the Democratic Party today other than an angry antiwhite, anti-Christian coalition?

Nixon tried to placate both sides by doing a little of everything. He publicly supported the Fair Housing Act (signed into law in April 1968), talked of winning over the black middle class, and, in a speech written by William Safire and titled “A New Alignment for American Unity,” called for “an alliance of ideas” uniting white Southerners, black militants, Eastern liberals, and Middle Americans. Buchanan, who had not seen the speech beforehand, thought it ridiculous and could not believe that Nixon actually believed what he was saying. Yet the President did give the speech. Worse, he proceeded to govern as if he believed it.

Nixon also made a play to win the Jewish vote by calling for Israeli military supremacy in the Middle East, backed by the United States. (Safire had long been arguing for such a course.) That Nixon would advocate a policy so clearly at variance with his generally sound geopolitical thinking boggles the mind, but how did it fare politically? Nixon won 17 percent of the Jewish vote, and Humphrey 81 percent.

Watergate remains, even for those who lived through it, somewhat of a mystery. How is it possible that the American press could bring down a popular president? Why would Nixon alone be driven from office, when his predecessors as well as his successors were guilty of similar, or even worse, abuses of power?

Many have suspected that there was more to Nixon’s downfall than a crusading press and a vindictive Democratic Party. Roger Stone worked for Nixon’s election in 1968 and for his re-election in 1972, when he was the youngest member of the Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP). Later, he became a close aide to Nixon and one of the architects of his public rehabilitation.

Stone believes that Nixon was done in primarily by the national-security establishment. The Watergate break-in was deliberately botched. Bob Woodward, a former naval-intelligence officer, was fed damaging information by Gen. Alexander Haig, the Pentagon’s man in the White House. The Washington Post, moreover, had a long-standing working relationship with the CIA. Nixon may have made the same mistake Kennedy had made, thinking he was free to pursue foreign policies he believed were right for the country. Still in shock over the disaster of Vietnam, the CIA and Pentagon were angered and alarmed by Nixon’s rapprochement with Red China and his détente with Soviet Russia. How far would he go? They did not want to find out. Worse still, Nixon was pressing CIA director Richard Helms to turn over the agency’s records on the Kennedy assassination. Stone argues that Nixon knew that the CIA and LBJ were behind the shooting, and that those in the know knew he knew. Later, Nixon used this knowledge as leverage to extract a presidential pardon from Gerald Ford (through Haig’s mediation), something that all of Ford’s advisors urged him not to grant, for fear it would harm him politically in 1976.

Stone is not breaking new ground here. His research supports the work previously done by Jim Hoagan (Secret Agenda, 1984) and Len Colodny (Silent Coup, 1991). Together, these works provide a credible case that Nixon was the second president in ten years to lose his office because of the machinations of the CIA. That the counterculture and the press were allied with the establishment they professed to hate did not bode well for the future. Rather, it seems to have presaged the multicultural imperialism of the present.

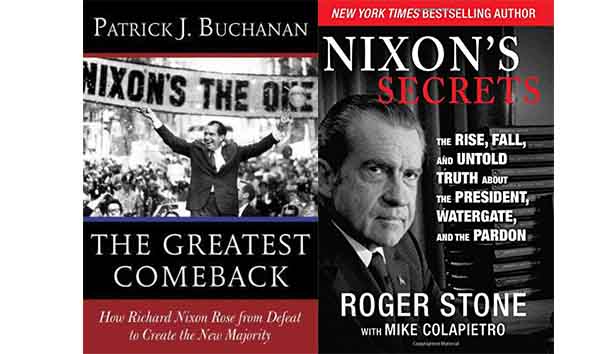

[The Greatest Comeback: How Richard Nixon Rose From Defeat to Create the New Majority, by Patrick J. Buchanan (New York: Crown Forum Publishing) 391 pp., $28.00]

[Nixon’s Secrets: The Rise, Fall, and Untold Truth About the President, Watergate, and the Pardon, by Roger Stone with Mike Colapietro (New York: Skyhorse Publishing) 669 pp., $24.95]

Leave a Reply