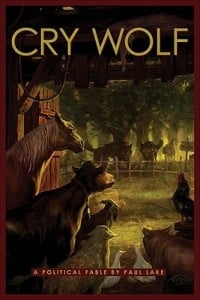

From Aesop on, through Ovid, Chaucer, La Fontaine, and Dryden, to George Orwell, the genre of the animal fable (whether in verse or prose) has been useful to moralists and critics of human behavior. Paul Lake’s satire belongs to this lineage. Identified as “A Political Fable,” it is, as the back cover asserts, a 21st-century Animal Farm. Lake, who teaches at Arkansas Tech, is poetry editor for First Things. He has published one previous work of fiction, Among the Immortals (1994), and two collections of verse, Another Kind of Travel (1988) and Walking Backward (1999). He is also a fine critic of poetry. The present book illustrates his excellent judgment in another field: politics. In a style that is accessible both to adult and younger readers, it brings to life the value of order and tradition, the need for limits, the danger in great abstractions. It suggests that politics and culture (including high culture) are closely, if often subtly, connected, and that the outrages in contemporary America threaten our state of mind as well as the body politic.

Lake’s story concerns a farm taken over, after the owner’s death, by the domestic animals. Domestic is the important word: They are tame, trained, cooperative, orderly. By working together and using hoof, mouth, and beak, they have managed to preserve their home and feed themselves and their young. They have a simple constitution, a few laws, and traditions (most important, the winter pageant, which resembles a manger scene). Each animal has a voice; disagreements are handled by wise elders or vote. As a matter of survival, they have defined themselves as what they are not—feral. Their fences have kept them from predators’ raids on themselves and their food supply; the call of the wild is precisely what they do not wish to hear.

Trouble begins when a wounded doe (nicknamed Xena) takes refuge on the farm; despite the firm “no trespassing” rule, she is allowed to stay while she either finishes dying or recovers. She gets stronger and, on her own, leaves, thus posing no threat. Readers can guess what occurs next. The unfortunate example of an innocuous incursion leads to tolerance of other invaders. First comes a raccoon, then a few more, then possums, beavers, and other species, all with good reasons (their needs as disadvantaged creatures who must forage to eat)—and, at the beginning, also with offerings. The raccoons and possums vaunt their ability to use their paws as hands. By climbing to the high branches in the orchard, they can pick fruit that the horses cannot shake down; they can also milk the cows and carry buckets. Beavers, felling saplings, can provide replacement poles for aging fences. This help is welcomed as useful. Shortly, it is viewed as necessary; these animals, it is said, contribute to increased harvests by doing jobs domestic animals cannot do (true, in a few cases) or (through increased indolence) will not do.

The feral animals bring dependents and members of extended families. Soon, they are swarming everywhere. While some are orderly, others quickly become unruly; thieving is common, and, later, the rooster is beheaded. Citizenship having been granted to the first raccoon, others demand it, insisting on their right to share the original occupants’ rights. Some demands are patently absurd; should the ferret or fox be allowed to dwell in the henhouse, for instance? The feral invaders also demand that schooling, formerly just a short course in civic behavior, become a reeducation enterprise—in fact brainwashing, intended to undermine the principles of the community, promote biodiversity and many-animalism, and create feelings of guilt in the original residents, who are accused of breedism. Those who stubbornly reject the new watchwords will not, it is scarcely necessary to add, pass the course. A new curriculum, “Raccoon Studies,” is introduced. In all their revindications, the feral residents are aided, alas, by Athena’s bird, the owl, called Professor, who argues, for instance, that the distinction between wild and tame is “an illusory construct,” an example of flawed and binary thinking. Professor! By just one word, the author suggests where much responsibility lies for the “reeducation” so broadly imposed today.

The newcomers create their own societies or houses, to which the domestic animals cannot be admitted because the wild breeds have been, as they argue, disadvantaged, oppressed, and, most of all, “marginalized” or excluded—so that they have the right to special privileges as compensation. They, of course, cannot themselves be breedists. By appealing to a “higher law,” they demand the rewriting or “re-interpreting” of the constitution and modification of traditions such as the pageant. A great exploit of yore on the farm—killing a marauding bear—which was formerly celebrated is stricken from the community’s oral tradition; what right, ask the wild animals (overlooking, of course, the killer instincts of some of their own), had the farm animals to resort to violence?

The very ideas of property—that someone can call his a portion of the earth—and of identity and borders are challenged in the name of what the feral animals define as justice: equality (for them, of course), fraternity (for them, of course), and “level ground” (as they define it). The domestic animals’ speech is monitored, and those who reveal xenophobia by stereotyping, “profiling,” or referring to “wild” animals are rebuked and sent for sensitivity training, even detained. The beavers cease repairing fences, as they become regarded as the products of violence and the urge to dominate. When resources diminish as the invading population increases, the feral elements demand that the domestic animals reduce their own breeding, in the name of “fairness.”

What amounts to an aggressive takeover does not go unchallenged. Gertrude, the goose, is valiant in her resistance, as is Shep, the border collie, firmly devoted to law and order, but accused on that account of “brutality.” What is fair as well as reasonable, they argue, would be to protect their property, provide for themselves and their offspring, and thus maintain their well-established community. The hens, the most vulnerable, feel particularly threatened; they have seen their eggs and chicks disappear, and a dowager hen is devoured by a coyote. But other residents refuse to look beyond their immediate interests to acknowledge the real evil that has come upon them. They consent, tacitly, to what amount to “treaties” with the “forest-born” (the mandatory euphemism for feral). The pigs, with their huge appetites and inherent sloth, argue for the imported laborers. The sheep are uniformly foolish, docilely swallowing and regurgitating the invaders’ propaganda. Confident in their size and strength, the stallion, rearing on his hooves, and the bull, with his longhorns, perceive no danger.

It would be cheering, if only briefly and in the mode of the imaginary, to report that Gertrude, Shep, and their allies do make reason prevail in the end. But Paul Lake does not want us to see political and social conditions in America today as “cheering.” The fox is in the henhouse, having been invited; “guest workers” and their broods and kin are here to stay, legally or illegally (it makes little difference), with education and medical care provided at no cost to them; the “big animals” who profit from the labor of these guest workers do not wish to send them back; the “many-animalists” have imposed successfully their principles and codes; local traditions, national images, and a shared culture developed over centuries are assailed as “oppressive”; and, worst of all, dangerous enemies move about with impunity, take over neighborhoods, cry “breedism,” and garner funds with which to blow us up, with the help of other foreigners abroad. Borders have become a fiction. (Why does anyone expect U.S. occupation forces to patrol successfully the long Iraqi-Syrian border when we cannot, or will not, secure our own borders in North America?) By the conclusion of Cry Wolf, foxes, coyotes, and other predatory animals have discarded the pretense of law and returned to the anarchy of nature, attacking chickens, geese, and dogs. Deeming the time right, wolves join them. At the end, a raptor owl descends “like a thunderbolt” on a chick, and a great, hungry bear with huge paws makes for the Hereford cows, which the bull, powerful as he is, can no longer protect. “Bloody mayhem” follows.

The transparency of this satire does not make it naive. Great satirists, from the ancients to Swift, Voltaire, and Anatole France, have favored broad strokes of the pen; satiric effectiveness comes from combining the ingenious with the obvious. The inner logic of Cry Wolf is just right. Cleverly devised and well developed, its animal equivalents of certain human institutions and behavior provide a pointed, often wry, but ultimately grim allegory of Western nations in recent decades. Developments that still pass unnoticed by some Americans because they are gradual and quotidian or supported by propaganda in the press and schools may be lethal; one need think only of the events of September 2001, demonstrations by hostile immigrants in Europe, and the aggressive invasion of our southwestern border. A condensed tale such as Paul Lake’s, dealing with a small but representative society mirroring ours, identifies present dangers and pictures what awaits us. Read this book yourself, and, as an antidote to multiculturalist diets in nearly all schools, get copies for students you know.

[Cry Wolf, by Paul Lake (Dallas: BenBella Books) 196 pp., $12.95]

Leave a Reply