It must surely embarrass John Miller and the other Francophobic neocons to realize that one of the quintessential American institutions was founded by an intrepid French missionary, who offered this vision for his action: “I have raised Our Lady aloft so that men will know, without asking, why we have succeeded here.” And it is a reflection of Father Sorin’s adopted country that the University of Notre Dame du Lac first achieved great success in the eyes of Americans by its excellence in a game invented in America, under a metonymic nickname honoring America’s most representative Catholic immigrant group but embracing all of them.

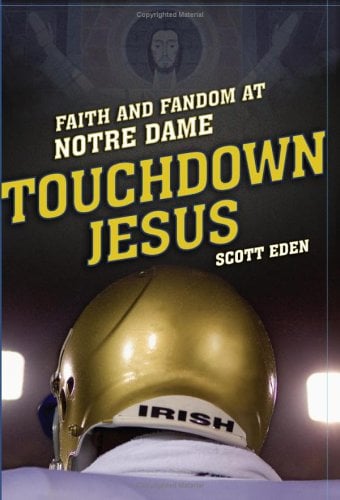

The story of how Notre Dame first achieved that excellence under Knute Rockne was told well by Murray Sperber in his early 1990’s Shake Down the Thunder: The Creation of Notre Dame Football. And the story of how Notre Dame has retained an unparalleled national following among American college football fans, despite not winning a national championship since 1988 and being mired in football mediocrity for a decade, is well told by Scott Eden in Touchdown Jesus: Faith and Fandom at Notre Dame.

Eden’s book is organized around the 2004 season, which ended with Notre Dame firing its first black head football coach, Ty Willingham—a move that generated great controversy in the sports pages but little among Notre Dame fans. But Eden consistently returns to his themes of faith and fandom at Notre Dame in a way that is even more embarrassing to the neoconservatives than the French origin of the school. In an age when we are asked to believe that there is nothing more to being an American than arid intellectual assent to a clause from the Declaration of Independence, Eden’s story is a reminder that what actually moves Americans are feelings far more elemental than abstract political ideology and adherence to propositions far older than those set forth by Thomas Jefferson.

What sets Notre Dame apart from other college-football programs are its “subway alumni”—fans in every area of the country who follow Notre Dame football despite having no formal connection to the school. (The term was coined to describe the fans, often from the poorer sections of New York City, who poured out of the subways to root for the Fighting Irish in the epochal games against Army from 1923 to 1946, played first at Ebbets Field, then at the Polo Grounds, and finally at Yankee Stadium.) As Eden writes,

The reasons why these prototypical subway alumni made their short pilgrimages were easy enough to discern: they felt a deep affinity for this team made up of Catholic schlumps just like them—Irish and Polish and Italian mostly.

Eden notes that “their passion for all things Notre Dame grew almost nationalistic in its fervor” and that “[t]heir Notre Dame fanaticism was bound up with notions of religion and ethnicity and class.” Such feelings existed across America: “Whenever Catholic immigrants settled . . . they also gave rise to subway alumni.” As Eden chronicles, the passions awakened in the Rockne era are alive today, oftentimes passed down from grandfather to father to son.

When these passions first arose, however, they were far less controversial than they are today, when public expressions of religious sentiment are frowned upon and the notion of ethnic pride for whites is seen as toxic. Fr. John O’Hara, who was president of the school in the period following Rockne (and later Cardinal O’Hara of Philadelphia), called the school’s football team “an apostolate for the working of incalculable good” and believed the team’s success on Saturday was related to the number of daily communicants at the school the week before. O’Hara’s successor during Willingham’s time as coach, Fr. Edward Malloy, by contrast, seemed embarrassed by football; the connection between the game, religion, and ethnic identity; and everything else that set Notre Dame apart from what one of his flunkies termed the school’s “aspirational peers”: such thoroughly secular places as Stanford (whence Willingham came), whose sports teams generate little passion and none of whose (comparatively few) fans follow their teams because they see in them a reflection of who they are or of what, at the deepest level, they believe.

Notre Dame’s continuing mediocrity under Willingham was certainly a trial for the school’s loyal fans. A black Methodist from North Carolina with no obvious affinity for Notre Dame and its football tradition, Willingham was hired after Notre Dame was lobbied by Jesse Jackson; Eden quotes one fan (a poster at the aptly named ND Nation website) as writing, “Ty is out of place here. Wrong guy for this program and its history . . . Other than PC, he has nothing going for him as regards the world of ND football.” This fan undoubtedly spoke for many, and it would be wrong to describe such sentiments as “racist,” the word bandied by sportswriters after Willingham was fired. Notre Dame fans had long accepted players and even coaches who were not Catholic (including Rockne, who did not convert until 1925, under O’Hara’s tutelage), and, by 2004, the majority of the school’s players were black, as was the case with almost all schools in the NCAA’s Division 1-A, while Notre Dame does a markedly better job of graduating its black athletes than do its competitors in football.

It should not be seen as scandalous that at least some (and probably many) Notre Dame fans felt an emotional distance from Willingham, any more than one would be shocked if Grambling fans were put off by a decision to make an Irish Catholic from the Northeast their coach. Coaches are not ordinary job seekers, and they have, in addition to their coaching duties, an important symbolic role. Such distancing as Willingham experienced thus represents not hostility toward other groups but a natural affinity for one’s own, an affinity that is not invidious but healthy. A man who does not love himself will produce nothing of value, and neither will a people lacking in normal feelings of self-regard. Certainly, Notre Dame could never have acquired its large following had American Catholics disdained their heritage. To be successful at Notre Dame, a coach must combine “a reverence for Notre Dame as deep and loyal as any subway alumnus’s and a whole lot of winning.” Willingham failed on both counts.

Apart from insisting that Willingham’s dismissal was not racist, Eden largely avoids addressing the tension between Notre Dame’s fan base and a coach who embodied none of the attributes that attracted that base. He does, however, argue persuasively that striving for excellence in all things, including football, is a reflection of the charism of the Holy Cross order that founded Notre Dame and that “Football . . . had got all bound up at Notre Dame with Catholic identity. Losing the first was a symptom inherent in moving away from the second.” And Eden at least suggests that the selection of Fr. John Jenkins to replace Malloy not only made possible the replacement of Ty Willingham with Charlie Weis but might lead to a reaffirmation of Notre Dame’s Catholic identity.

The ethno-religious nature of much of the support for Notre Dame is not unique in American sports. As Steve Sailer has noted, “NASCAR has become a covert ethnic-pride celebration for red-state whites of Northern European descent.” Such subsidiary allegiances actually help to create, rather than weaken, an authentic American identity. Even those who follow neither sport sense that they are important American institutions, while, for their fans, both Notre Dame football and NASCAR help symbolize what they love about America and serve to focus deep, powerful, and elemental identities on the broader backdrop of American patriotism.

Indeed, there is a reason that the prisoners in Stalag 17 (and other films like it) were more concerned with whether a new prisoner knew who played in the World Series than what Jefferson wrote in Philadelphia. Eden recounts a telling anecdote about New York Post editor James Wechsler, who was scornfully told at a dinner party in 1974, after expressing an interest in the outcome of the Notre Dame-Alabama game, “It’s the most American thing you can do.” A love for and immersion in the art, culture, and folkways created by Americans (including the great spectator sports invented by Americans) is a surer indicator of being an American than a professed desire to join the “proposition nation.” What it means to be an American is tied up with Notre Dame football (and numerous comparable institutions), and Eden is certainly correct when he writes that “Notre Dame and its football mean more to great numbers of people . . . than a sport involving boys and a field and a score at the end of the day.”

[Touchdown Jesus: Faith and Fandom at Notre Dame, by Scott Eden (New York: Simon & Schuster) 368 pp., $25.00]

Leave a Reply