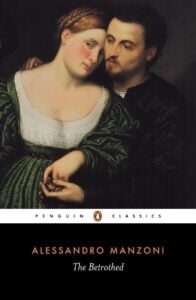

But besides the special ornaments that she had put on for her wedding morning, Lucia had one which she wore every day—a modest beauty, which was thrown into relief and enhanced by the various emotions which appeared in her face—a great happiness, qualified by a faint air of confusion, and that calm melancholy which appears from time to time on the face of a bride, not detracting from her beauty, but giving it a special character.

So Alessandro Manzoni described his heroine at the beginning of his 1827 novel, The Betrothed, hailed as the greatest of Italian novels. Lucia does not know it, but her husband-to-be, an upstanding lad named Renzo, has just learned that the local strongman, Don Rodrigo, from his castle full of flunkies and thugs, has compelled the parish priest, with a thinly veiled threat of death, to put a stop to the marriage. That evil deed sets the novel into motion.

When I was last in Italy in 1998, visiting cousins, touring the land with my wife and our young children, and searching for early editions of Torquato Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata (“Jerusalem Delivered”), I asked people wherever we stayed whether school children still read that great Renaissance poet, the ardent Catholic who often teetered on the brink of madness and sometimes toppled over the brink. Yes, they did, I was told, though they didn’t care for it much. Manzoni was another matter. I promessi sposi (“The Betrothed”) was beloved by everyone. Why not? You have plenty of adventure; hair’s-breadth escapes; a sweet and saintly girl; a brave lad who has to learn self-restraint, perseverance, and forgiveness; a remarkable conversion to Christ; the most powerful portrayal of a holy priest in all of Western literature; good people and bad, wise and foolish; and all of it set against historical events from the early 17th century, meticulously researched by the author, not just to lay the groundwork for the tale but to deepen our vision of man and his deeds.

“Renzo e Lucia!” exclaimed the landlady at our pensione (guest house). That was then. I have no idea where the Italians now pitch their cultural tents. Perhaps they have yielded to the waves of mediocrity and trash that wash up on their shores from their sick sister across the Atlantic. I hope not, but I am not sanguine about it. Does the British laborer read Dickens? Does his American cousin read Faulkner? We may be thankful if they read at all. I can tell you that Church music in the land of the great Renaissance composer Giovanni Palestrina is as bad as ours, sounding like nothing Italian, nothing that will outlast the centuries, but rather like the jingles of commercials or like show tunes when there are no longer any good shows.

But even if Italian schoolchildren do still read Manzoni, why should The Betrothed be taught only in Italy? It is a book for mankind, for the ages. Yet it is just such books that can hardly be taught in American public schools. In a broad sense, they are too religious. They are also—how to put it?—too universal, and not easy to conscript into the latest political cause. The Betrothed, The Brothers Karamazov, Les Misérables, Kristin Lavransdatter, Bleak House—all too powerfully themselves—demand that we submit to their wisdom rather than that they should tamely submit to ours. Still, you might suppose that some brave soul could teach them. Yet I find it impossible to imagine. Why? And what—to take The Betrothed as a powerful diagnostic case—do we lose by the failure?

First, on why it is impossible to imagine. It is not simply that teachers in our schools have not read much of the greatest literature written in their native language, let alone in that of others. It’s that they would not read such books. Their preferences show in what works they do assign, never for artistic merit, which they have not been taught to judge, nor for telling permanent moral truths about mankind, which truths they do not believe in, because outside of the sciences—and even those are in doubt—there is supposedly no objective truth at all.

Let me illustrate. “Books Banned in Oklahoma,” read recent headlines generated from a press release by the nonprofit PEN America, shaped with an undercurrent of contempt for people who do not live in Boston, Seattle, or Los Angeles. If you read further, all you find is that concerned parents in a few school districts questioned whether some books should be included in school curricula. Examine the list, and you find one or two great books, such as William Golding’s Lord of the Flies and Frederick Douglass’s autobiography. You also find one or two very good books on the usual racial controversies of our time—as if that is all there were to talk about and as if nothing had changed in America in the last seventy years—such as Lorraine Hansberry’s play A Raisin in the Sun and Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. The rest, and the great majority, of the “banned books” are lots of what I’ll call YANT, Young Adult Narcissist Twaddle, almost all of it about sex, race, and “identity.”

What are the wearisome messages of this YANT? That bullying and shaming are bad—except when the right people, for reasons of “inclusion,” drive certain social scapegoats into the desert. That we must all bow down before “diversity,” inevitably monochromatic and time-bound, in a lot of shades of pink. That we must all get in touch with some vaporous authentic self, floating in the miasma of an imagination fed by mass media and mass schooling. That we should all gaze at our navels—supposing that we haven’t mutilated ourselves and still have one.

Any tale of self-determination or conquest must have an opposition to overcome, and the articles about all the terrible “banning” in Oklahoma and elsewhere in Middle America follow along the well-worn track. Broad is the way that leads to conformity, and many are the souls who swagger thereon. Who are the book-banning villains? Religious people, meaning bigots; people who believe there are two sexes, meaning bigots; people who judge that self-destructive habits—and not racism—are what now bedevil black Americans the most, meaning bigots. The plots write themselves.

A “transgender girl” is not a girl pretending to be a boy, but a boy pretending to be a girl. So, I suppose, a “trans-species cat” is no cat, but a spoiled girl who raises her paw in class and says, “Meow.”

“Some of the works banned in Oklahoma,” according to another article in Newsweek generated by the PEN America release (and begging questions all the way, and lying, because not one work actually has been banned)

deal with LBGTQ rights, with a particular focus on transgender issues. They include Jeff Garvin’s Symptoms of Being Human, which deals with gender fluid adolescents coming of age, and George by Alex Gino, a novel focused on a transgender girl.

I pause to untangle the knot. A “transgender girl” is not a girl pretending to be a boy, but a boy pretending to be a girl. So, I suppose, a “trans-species cat” is no cat, but a spoiled girl who raises her paw in class and says, “Meow.”

Now, even the most faddish of school librarians in Enid and Muskogee would not admit just anything to the stacks. There isn’t room, and they themselves would say that certain things are not fit for children in public school. Books of Christian theology or philosophy, such as Augustine’s City of God? The title alone sends chills up the spine. But a graphic novel about a gay teen romance? Sweets for the sweet.

So the question is not whether librarians, teachers, and parents choose what goes into a library and what doesn’t, or what is taught in an English class and what isn’t. It is how to separate the good from the bad (artistically, but also morally), the true from the false, the wholesome from the sick and depraved.

That task isn’t so hard if you’re willing to yield to the judgment of mankind across the ages. Tennyson belongs because Tennyson is a titan of English verse,

because he gives you fascinating glances into the classical past, the Christian faith he tried to hold, the ever-fruitful legends of Arthur and his court, and the tumultuous age in which he lived. Melville belongs because his prose poem Moby-Dick, with all its stylistic peculiarities, addresses the mysterious darkness of life as well as any work ever has, exploring the caves of the human heart, where stalactites glow with a strange light, and eyeless fish swim in the waters. And Manzoni belongs: the man who grew up in the atheistic salons of revolutionary France but who turned to the Catholic faith and became an ardent believer even as he was also an ardent patriot, wanting Italy to belong to Italians and not to Napoleon or Maximilian; the man in whose honor Giuseppe Verdi, a secular liberal, composed his famous Requiem.

But we shouldn’t assume that teachers can teach Tennyson. They cannot teach what they cannot comfortably and knowledgeably read. That is another grubby secret. Nothing in their preparation prepares them to read Tennyson’s work, let alone that of Chaucer or Milton. YANT is a refuge for the timid and the frail.

What then, do we miss, when we shun Manzoni? A shrewd and profoundly political vision into the cross motives at play when men act in concert.

The novel’s hero, Renzo, had to flee to Milan, where his friend, the holy priest Father Cristoforo, sent him to take refuge at the Capuchin monastery. When he arrives, the city is in an uproar. Poor harvests, made worse by mercenary armies and their rapacity, have resulted in a shortage of grain, meaning a shortage

of flour from the millers, and a shortage of bread from the bakers. But people must eat. So they riot, leaving reason behind. They insist that the millers and bakers are hoarding to drive up prices. Does that sound familiar? The crowds grow dangerous, not only to social order but to themselves and their prospects.

“In popular uprisings,” Manzoni wrote, drinking from the springs of history modern and ancient,

there are always a certain number of men, inspired by hot-blooded passions, fanatical convictions, evil designs, or a devilish love of disorder for its own sake, who do everything they can to make things take the worst possible turn. They put forward or support the most merciless projects, and fan the flames every time they begin to subside. Nothing ever goes too far for them; they would like to see rioting continue without bounds and without an end.

But there are others, he continued, who try to steer the crowd in a saner direction, “inspired by friendship or fellow-feeling for the people threatened by the mob, or by a reverent and spontaneous horror of bloodshed and evil deeds.”

Renzo is in the latter group, but that group is not necessarily rational either. For the two kinds of people “vie with each other in spreading rumors calculated to rouse the passions and direct the actions of the mob,” and we are not talking about outright lies, because those who spread the rumors may well believe them, credible or no. Each group seeks “the key slogan which, once taken up and shouted loudly by the greater number, will simultaneously create, express and confirm a majority vote in favor of one party or the other.”

One half of the Milanese mob desires to see the bakers as actively starving the people, and that is nonsense; the other half—Renzo’s half, which gains the upper hand—desires to see the Grand Chancellor Antonio Ferrer, who comes on the scene to save the commissioner of public welfare from the mob’s violence, as a saint who loves the poor. That, too, is nonsense.

“The young hillman was charmed by his courtesy,” Manzoni wrote, for the sturdy Renzo has helped clear a path for the chancellor, “and almost felt that he was now a personal friend of the great man.” But had it not been for Ferrer’s capitulation to the demands of unreasoning citizens—he attempted to enforce price controls on bread—the shortages would not be so dire. You cannot compel economic realities to play by your imaginary rules. In his measures, whether motivated by goodwill, by a desire to curry favor, or both, “Ferrer was behaving,” Manzoni wrote, “like a lady of a certain age, who thinks she can regain her youth by altering the date on her birth certificate.”

In his deep consideration of the human heart, Manzoni ranks with Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, but without the occasional creepiness of the former and the more than occasional preachiness of the latter.

But there are more important concerns than the political and the economic. In his deep consideration of the human heart, Manzoni ranks with Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, but without the occasional creepiness of the former and the more than occasional preachiness of the latter. How fine it would be for young people to read an author who does not permit even his most wicked characters to go unaffected by promptings of humanity and the call of God! Rather, those nudges form a part of their torment and can goad them on to deeds of greater wickedness.

When Father Cristoforo loses his patience and says that the curse of God has already fallen upon Don Rodrigo’s house, that nobleman, that boss in crime, “could not find a moment’s peace at the thought that a friar had dared to come and attack him with words.” While he tries to figure out how to avenge himself, “the words with which Father Cristoforo had begun to prophesy before him rang in his ears, a shudder ran through his body, and he almost abandoned the idea.” But the portraits of his ancestors glare at him from the walls, one a magistrate, “the terror of litigants and lawyers alike,” another a great lady, “the terror of her maids,” another an abbot, “the terror of his monks.” Don Rodrigo is caught in a tradition of evil, one that uses the Christian faith as a cloak, and he has neither the strength nor the humility to get free.

When he tries and fails to kidnap Lucia, whom he wants as a mistress, and she gains the protection of a convent he cannot break into without public disgrace, Don Rodrigo turns to a far bigger crime boss than he, an historical figure whom Manzoni simply called “The Unnamed.” This man has lived a life of utter willfulness:

To do whatever the laws forbade, or any other power opposed; to be judge and master in the affairs of others, in which he had no interest but the love of command; to be feared by everybody; to oppress those who were used to oppressing others—such had always been that man’s principal passions.

Those passions have oddly made him dependent upon the very sinners for whose benefit he has exercised his fearlessness and his carelessness of morality. “Occasionally the weak would come to him, after suffering oppression at the hands of some bully,” Manzoni wrote, and then the Unnamed might take the weak man’s part and compel the bully to make reparation, so that the people nearby would call down blessings on his head, “but more often—as a general rule, in fact—his power was exercised on behalf of evil intentions, atrocious revenges, or tyrannical caprice.” Such is the Equalizer, we may say, in real life.

The Unnamed, then, has Lucia kidnapped, and he brings her to his mountain fastness, but she unnerves him. Not by angry words, not by some Hollywood display of girl-strength, at which such a man would have snorted in contempt, but by her innocent terror, her begging him to let her go to her mother, her reminding him that he too had a mother once, her promise to pray for him if he would do one deed of mercy—and this man with a bad conscience is struck. He goes to his room that night, and what can he do? Manzoni’s rendering of his struggle is worth a shelf full of books on psychology:

Caught in the toils of self-examination, the unhappy man found that to explain a single action he must embark on a review of his whole life. He went back and back, from year to year, from job to job, from bloodshed to bloodshed, from villainy to villainy. Every detail of his actions appeared before his mind’s eye; he knew them well, yet saw them as if for the first time, in isolation from the passions that had led him to will them and to carry them out. They came back to him in their full enormity—an enormity which the passions had previously concealed. Those crimes all belonged to the man who had committed them—in fact they were the man who committed them.

He takes a pistol and spends the night cocking it and uncocking it, wavering, though he hardly knows it, between eternal death and eternal life.

One of the sillier results of a Marvel-comic-book view of the world is the notion that “good” people (who look and sound as surly and unpleasant as the “bad” people but are to be admired because they hold the correct opinions regarding race and gender) do not also walk through a moral valley of the shadow of death. The body armor of unthinking correctitude and the choreography of kick-punching self-righteousness protect the “good” people from evil, which surely cannot pullulate from the fens of their own hearts.

But when Renzo says to Father Cristoforo that if he finds Lucia has died—for plague has followed famine in Milan—he will take vengeance upon Don Rodrigo, the cause of all his ill, the priest, himself dying of the plague as he helps to minister to the thousands of souls in the great lazaretto (quarantine center), does not say, “I understand,” or, “I wouldn’t blame you,” or, “It would be just.” “Look around you!” he cries, gripping Renzo’s arm with one hand and sweeping with the other across the vista of misery before them.

Look and see who it is that chastiseth mankind, who it is that judgeth and is not judged, who layeth on sore strokes and who granteth men his pardon! And you, worm that you are, crawling on the face of the earth, you want to administer justice! You know what justice is! Go, wretched sinner, leave my sight! And I hoped—yes, I had hoped that before I died, God would have granted me the happiness of knowing that my poor Lucia was still alive, perhaps even of seeing her again, and of hearing her promise to offer up a prayer over my grave. Go! for you have robbed me of that hope. I know now that God has not left her in this world for you.

Those are not the last words. But when will our young people hear the like? What Father Cristoforo demands of Renzo, I say, is heroic, but of a kind of heroism of which the ancient pagan world knew nothing and of which our modern post-Christian world knows nothing. It is the heroism of giving up all pretense that you are good or good enough. It is the heroism of casting your lot with the most despised man of all, Christ bearing his cross up the mount of Calvary. It is to say, “I will surrender my anger, I will not pretend to stand in judgment over my brother’s soul, and I will acknowledge reality, which shows me that those who call for justice without mercy or forgiveness will get more justice than they bargained for.”

I do not wish to play the spoiler. But there is one more thing Manzoni gives us that students will get nowhere else: a powerful appraisal of an institution that transcends the political, the economic, and the moralistic. It embraces, as Manzoni showed, many a double-talking coward, such as the curé Don Abbondio, who gave in to the wicked demands of the crime boss and would not marry Renzo and Lucia; many a shallow and greedy man; many time-servers, even people who enter the religious life to realize dreams of ambition and power. But it did things no merely secular institution ever did or ever would conceive of doing. It went shoeless to the poorest of the poor. It brought learning to the most ignorant. It gave hope to people in despair of their sins and the

irremediable harm they have done on earth. It gave courage to the faint of heart, rest to the weary, hope to the dying and a place of rest for their mortal remains. It did so while lifting the souls of ordinary people to visions of which not even the wisest of the pagans could conceive. That institution is the Church.

When the plague struck Milan, the doctors warned the governor about it, but he had more important things on his mind: war and international politics. It fell to the priests of the diocese, led in words and in deeds by the heroic Cardinal Federigo Borromeo, to care for the tens of thousands of the sick and the dying and the dead, to bring them food and water, to clean their sores, to protect them from predators walking on two feet, to give them consolation in their last hours, and to send them forth with blessings and with vital moral instruction if they survived and could leave the lazaretto. The Capuchins were especially active, led by Felice Casati, whom the provincial had sent to Milan to oversee the lazaretto for the physical and spiritual welfare of all suffering people. Manzoni, working from historical documents, wrote that Father Felice

inspired and controlled everything; he calmed riots, solved disputes, threatened, punished, reproved and comforted; he dried the tears of others and shed tears of his own. He caught the plague at the beginning of his ministry, recovered from it, and went back to his duties with renewed vigor. Most of his colleagues in the lazaretto died there with uncomplaining cheerfulness.

It was a dictatorship made necessary by circumstances, but Manzoni—no friend of royalism or of absolute rule—described it as a

good example of the strength and ability which the spirit of true charity can confer on men in any walk of life and in any period, when we see how stoutly the Capuchins bore that burden. There was beauty in their acceptance of the task, for no other reason than because there was no one else who would take it on, with no other object but that of serving their fellow men, and without any home in this world but that of a death which few men would envy, though it could truly be called enviable.

And they did this even while the secular authorities dragged their feet, and the people, made desperate by fear and misfortune and a willingness to believe the worst, spread rumors that it was all on account of evil people smearing poison everywhere. The scapegoat we will always have with us.

And so, from this greatness of mind and heart, this exemplar of artistic accomplishment, a work in which young people may learn of true heroism, the struggle between good and evil in singular souls, the heart of the Christian life, while gleaning knowledge of history and economics along the way—from all of this, we go to Sodom with sugar and spice, angry dystopian fiction devoured by people who, because they have no aim beyond the grub-work of this world, long to consider themselves oppressed; lonely un-children and un-adults from broken homes, with no cultural heritage, no songs in their hearts, and no knees in their souls to bend in devotion to God.

Leave a Reply