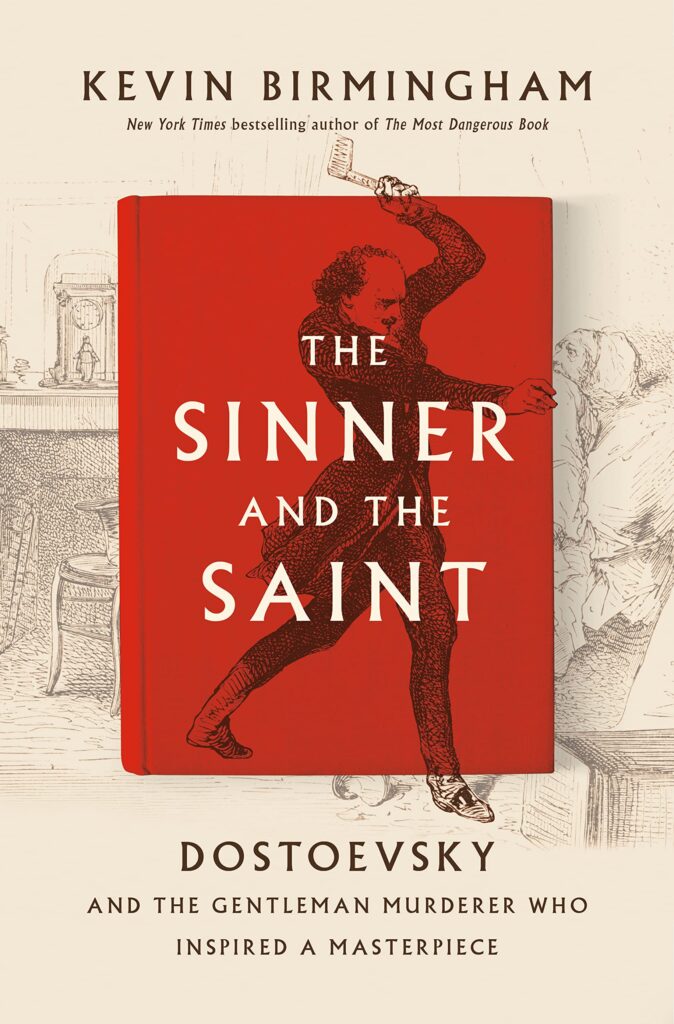

The Sinner and the Saint: Dostoevsky and the Gentleman Murderer Who Inspired a Masterpiece by Kevin Birmingham Penguin Press 432 pp., $30.00

In Under Western Eyes (1911), Joseph Conrad calls Russia “the land of spectral ideas and disembodied aspirations.” The power of such disembodied notions is very much a thematic focus of Kevin Birmingham’s latest book, a literary and historical study of Crime and Punishment (1866). In that groundbreaking opus, an intellectual murderer, his mind teeming with the fashionable nihilism of the day, justifies his brutal slaying of a pawnbroker and her daughter as the act of an extraordinary being to whom the conventional moral law does not apply.

The great value of Birmingham’s analysis lies in his painstaking reconstruction of those aspects of Dostoevsky’s life experience that fed the stream of creativity resulting in the unforgettable portrait of Raskolnikov, arguably the most brilliant psychological profile of a murderer in the annals of fiction. Nevertheless, while Birmingham’s book is as beautifully written as it is penetrating, it is flawed in its attempts to make a convincing case that the notorious French murderer Pierre François Lacenaire, executed in Paris in 1836, was a major inspiration for the novel.

While the events in Crime and Punishment are set in St. Petersburg in the early 1860s, the radical ideas that flourished then were already circulating in the 1840s, when Dostoevsky first settled in the city. In 1845 he published Poor Folk, a novel praised by Russia’s most respected literary critic, Vissarion Belinsky. It was Belinsky who introduced Dostoevsky to Hegelian thought and to the ideas of other Western thinkers like Max Stirner, whose philosophy of “egoism” was undergirded by a radical skepticism that verged on nihilism. Unlike Hegel, Stirner saw no value in the historical process. When all the religious and political illusions harbored by men have been stripped away, he argued, what is left is the insatiable individual. “I alone am corporeal,” he wrote, dismissing all else as hopelessly abstract. “Now I take the world as what it is to me, as mine, as my property; I refer all to myself.” Contra the Hegelians, Stirner believed that “anyone could be a Napoleon.” If one should choose to assassinate the tsar or merely murder some random stranger, the authorization for such an act lies entirely within one’s subjective preference.

Such were the “floating ideas” that swarmed in the taverns and private gatherings of the Russian capital in the 1840s, forming the backdrop for Crime and Punishment. While Dostoevsky initially had reservations about the ideas of Stirner and others, in 1847 he was drawn into the embrace of the Petrashevsky Circle, named after its flamboyant but mysterious leader, Mikhail Petrashevsky, who “stalked the streets of St. Petersburg in a long black cape” and “celebrated Jesus’s death as if it were the resurrection.” The Petrashevists met regularly to debate socialism and other utopian schemes, though Dostoevsky’s main interest was the emancipation of the serfs.

In 1848, as democratic revolutions spread across western Europe, Tsar Nicholas I placed his so-called Third Section (his secret police) on high alert. Informers were burrowing into groups like the Petrashevsky Circle all over St. Petersburg. On more than one occasion, Dostoevsky unwisely spoke of revolt against the regime, convinced that only by its overthrow would the serfs be liberated. In April, 1849, many of the Petrashevists were rounded up and imprisoned, including Dostoevsky. After months of interrogation, they were sentenced to public execution but were saved by a last-minute reprieve. The “execution” was pure political theater, staged by Nicholas to make a public statement. The subsequent exile to Siberia was quite real.

Although Dostoevsky’s exile lasted for a decade, only a few of those years involved hard labor in a prison camp. It was there, however, that he came into contact, for the first time, with hardened criminals, many of them murderers. As Birmingham notes,

Now he was living with murderers … sharing tables and latrines with them, hauling bricks with them, sipping water from the same ladles. The complexities of murder, all the winding paths that might lead someone to take another person’s life, were just beginning to come clear.

Writing was forbidden in the camp, but Dostoevsky scribbled notes on any scrap of paper he could find. All these observations and scraps of dialogue eventually formed the basis for his semi-autobiographical novel, The House of the Dead (1861). But it is also clear that his portrait of Raskolnikov was already germinating in his prison notes, as he ruminated upon the various personalities of the murderers he befriended. In one instance he observed that a person kills out of “a convulsive display of his personality … a desire to declare himself.” Every murderer is a little Napoleon.

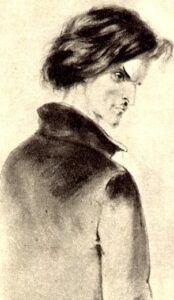

Lacenaire (from: Pierre

Théophile Junca,

lithographe, in the

Public domain, via

Wikimedia Commons)

When Dostoevsky returned to St. Petersburg in 1859, he was full of plans to collaborate with his brother, Mikhail, in founding a new literary journal. Their journal, Vremya (“time”), which first came out a year later, was not strictly literary but covered social and political issues as well. Searching for material, Dostoevsky ran across a booklet published in Paris some years earlier, a 32-page account of the life and murder trial of the aforementioned Lacenaire. That account was published in the second issue of Vremya, in 1861, translated by Dostoevsky himself. Birmingham would have us believe that Lacenaire’s story was a primary inspiration for Crime and Punishment.

To be sure, there are some similarities between Lacenaire and Raskolnikov. The former was from a family of some social standing and was well educated in Jesuit schools. Raskolnikov is from the lower nobility and also well-educated, though his family has become impoverished by the time the novel opens. Lacenaire was a voracious reader of all the new radical authors; so also is Raskolnikov. Lacenaire’s primary victim was an old woman; so also is Raskolnikov’s. Lacenaire’s weapon of choice was an ax; Raskolnikov butchers Alyona, the pawnbroker, with the same kind of weapon. It should be added that, like Raskolnikov, Lacenaire imagined himself to be one of those “extraordinary” individuals who had somehow transcended the moral law.

(from: Pyotr Mikhaylovich

Boklevskiy, in the Public

domain, via Wikimedia

Commons)

It is plausible to assume that some of these similarities were not accidental. No doubt, Dostoevsky’s interest in Lacenaire just three years before he began writing his great crime novel is sufficient reason to offer the French murderer as a possible model for Raskolnikov. However, it is highly questionable whether the parallels between the two murderers justify the six chapters on Lacenaire that are scattered haphazardly throughout Birmingham’s book. A single chapter would have been sufficient.

More important are the dissimilarities. Lacenaire was a cold and calculating poseur, a smiling, self-made caricature of the casual nihilist. He loved publicity and made a foppish public show of his own execution. He was, in short, a narcissistic sociopath. Raskolnikov, by contrast, shuns public attention. He is, despite his horrible deed, a loving, kindhearted son to his mother. Moreover, he worships the saintly prostitute Sonya, the woman who loves him because he once tried to save the life of her drunkard father and provided help to her desperate family. His mind, of course, is poisoned by “floating ideas,” but his spirit retains goodwill.

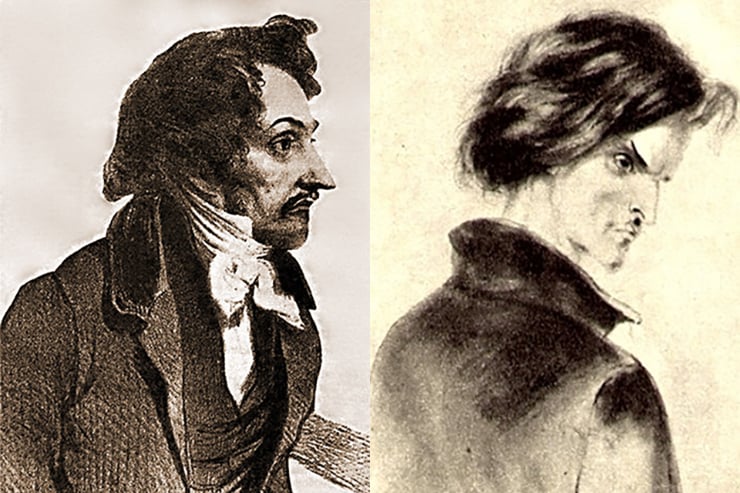

In fact, the genesis of Crime and Punishment did not come until after the death of Dostoevsky’s first wife, Marya Dmitrievna, who had suffered from tuberculosis for years. She succumbed early in 1864, and he was still in mourning when his brother Mikhail died of an abscessed liver. Now Fyodor was more deeply in debt than ever, in large part because he had promised Mikhail that he would take care of the latter’s family, but there were also debts to publishers and to those who had helped finance Vremya and a second journal, Epoch. Birmingham writes memorably that, in just a few months, the great writer’s life “had been chiseled down to a stump.”

Dostoevsky in 1863 (from:

А. О. Бауман, Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons)

He had managed to complete his Notes from Underground that year, but, still desperate for money, he fled to a German gambling mecca called Wiesbaden. He had gambled before and was sure now that he had an infallible “system,” but that of course failed. He found himself under virtual house arrest at the Hotel Victoria, near the Wiesbaden train station, waiting for someone, anyone, to respond to his pleas for money—just to pay his hotel bill. Convinced he would have been hauled off to jail if he had tried to leave, he sat in his room for weeks, half-starved and ignored by the hotel servants.

Sometimes, though, he was able to walk about the town, and one evening a new idea came to him. It was as if voices from the as-yet-unwritten novel had begun to speak to him, voices not yet attached to specific individuals. But as he recorded these details in his notebook, the faces of characters began to emerge. He began to visualize a murder scene. And that scene, including the murder weapon, may have been suggested by a news account he had recently read in a Russian-language newspaper about a man who had killed a cook and a washerwoman with an ax. Delirious, he scribbled for days with little sleep, filling almost 100 pages with erratic text and drawings of faces in the margins. Convinced that this would be his best novel yet, he wrote to every publisher he knew, but found no takers. Then, he appealed to a friend, Princess Shalikova, who urged her brother-in-law, Mikhail Katkov, the editor of the Russian Herald, to consider publishing a serialized version of the novel. Katkov took the bait.

By the time Dostoevsky returned to St. Petersburg in 1865, the new novel had acquired a name and a protagonist, but despite some help from Katkov, Dostoevsky’s creditors were hounding him, and he faced the very real threat of debtor’s prison. On top of that, his epileptic attacks were occurring with ever greater frequency. Nevertheless, he worked with almost demonic energy, discarding one draft after another, each one allowing him to burrow more deeply into Raskolnikov’s mind.

Wikimedia Commons)

Eventually, he shifted from a first-person, confessional account to a limited third-person narrative. Birmingham conveys this crucial shift:

What if the most intimate perspective isn’t actually the first person? What if we could be even closer to the murderer by lurking a half step behind him … [close enough] to think and feel what he thinks and feels not because the murderer narrates it but because we hear it slantwise from someone more lucid, someone who could be Raskolnikov’s double?

His double would be, of course, the third-person narrator, but one who is “invisible.” Such a narrator would internalize Raskolnikov’s “madness” to an uncanny degree.

A novel like this had never been attempted. To lure the reader into the mind of a killer, to virtually become that killer, and to witness the gruesome act itself as if one were an accomplice—this was something profoundly shocking, something that readers had never encountered. Edgar Allan Poe had explored such possibilities, but never with such realism. Dostoevsky himself was driven to the verge of madness by the mental and spiritual demands of Crime and Punishment. As Birmingham argues, the novelist began to “let his own uncertainty drive the novel.”

The numerous changes in the plot and the narrative perspective, and the ambiguous motives of the central character—all these contributed to the mixed reviews that the novel initially received and to the impression, according to one reviewer, that it was the product of a “diseased imagination.” But of course it was nothing of the sort. Upon repeated readings, it reveals spiritual depths that would become increasingly evident in the novels that followed, especially The Idiot (1869), The Demons (1872), and, above all, The Brothers Karamazov (1880).

Birmingham’s study is worthy of our attention; it admirably penetrates the mind of a great writer under extreme duress in the midst of producing his first masterpiece.

Leave a Reply