American literature, Wallace Stegner once observed, is not so much about place as motion: we are a restless people, and we write restless books that hurtle us from A to B with a blur to mark our passage. Discounting Stegner’s own lovely evocations of place in books like Wolf Willow and Grossing to Safety, one has only to think of the Pequod and Huck Finn’s raft, of Francis Parkman’s horse and Neal Cassady’s convertible, of Ken Kesey’s magic bus and Tom Wolfe’s chrome Spam-in-a-can rocket ship, even of John Muir’s buniony feet, to sec his point.

It is strange that in the catalog of contraptions and creatures that have propelled our literature, the semitruck should not figure more prominently than it does. Why do we have no great novels about Macks and Roadmasters and Peterbilts, no epic poems about balling the jack doing double nickels on the dime? Country music would be markedly poorer without our native leviathans; where would Red Sovinc and Hank Snow be without them? Transcontinental trucks have left scarcely a dent in our writing, although the image of them rolling down the endless highways of America is a ready-made metaphor, and the whine and hum of 18 wheels on asphalt is an authentically American idiom, as indigenous to these shores as jazz and popcorn.

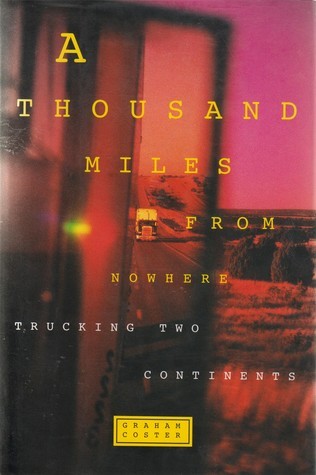

That it should take a British writer to introduce the diesel-belching rig to us as an object of literary investigation is another curiosity. That is just what the novelist Graham Coster—the author, fittingly, of a book called Train, Train—does with A Thousand Miles from Nowhere, a good serious book of literary journalism that coincidentally marks the return of the North Point Press imprint.

The British have always produced fine travel writing, a body of work sometimes marked by a certain snotty disdain for the local subjects and a quickness to take credit where credit is not always due. Among American travel writers, only Paul Theroux seems to have imported these attitudes, but Coster will have none of them. He has an open humor and a pleasant way, as when he explains that in his own country, his interest in trucks is not widely shared:

In Britain we like trains. We invented them. Therefore we don’t like trucks. Trains keep to their own neat ribbons of rail and stop at stations a mile out of town; trucks barge through half-timbered high streets and vibrate our Victorian sewage systems to pieces. A railway’ track says ‘within limits’; the tidal wave of spray that smacks you sideways on a rainswept M4 says ‘free for all’

When Coster undertakes to learn something of how a big rig—”artics” they’re called in Britain, misspelling included—is driven, he enters a world of power and terror. An instructor tells him, “You will be in charge of a very large killing machine,” and he learns that in guiding 11 tons that stretch 30 feet behind the driver’s seat, “you’re an oceanliner captain looking through your telescope for icebergs,” icebergs that include Volkswagens, horse-drawn carts, and just about every other vehicle Europe can toss out on the highways.

Theoretical education behind him. Coster is off to Russia—”straight on past the Pizza Hut, left at the Kremlin”—and ready to give the reader lessons in economics, sociology, and history. To the truckers of the European Economic Community, we learn, Hungary is the pirate nation of the highway, underbidding at catastrophically low rates to secure trucking for its huge state-run conglomerates; to sail under Hungarian colors is to hoist the Jolly Roger. In Europe, as in America, trucks account for more than 90 percent of all goods hauled, and, with markets expanding everywhere, Coster does not quite come out and say that nationalist tensions are likely to enter into the business with increasing frequency. The internationalist tensions are strange enough: thanks to EEC rules. Coster remarks, a contract trucker will haul a trailer full of ice cream from England to Russia, only to pick up another trailer full of ice cream in Germany to cart back across the channel: coals to Newcastle, sops to the tutelary spirits of overregulated trade.

Coster is generous with details, remarking that truckers are obsessed with the cleanliness of their vehicles not only as a mark of pride but also as a matter of economics; he is told dark cautionary talcs of one driver “whose dedication to squalor had managed to knock a good thousand [pounds] off the resale price of his truck.” As a travel writer must, he instructs in local custom, especially the ubiquity of Snickers bars as the ultimate road food. “They are as nutritious and healthy as a plate of eggs and bacon,” he writes without irony. He is less forthcoming with other elements of the trucker’s diet; as Bruce Chatwin said in The Songtimes, the interiors of Australia and other vast inland empires were settled by big trucks and amphetamines.

Longtime English haulers. Coster writes, dream of trucking America, piloting an “indestructible Kenilworth, the Harley-Davidson of trucks, with a wide road and a distant horizon to itself.” The second half of A Thousand Miles from Nowhere takes Coster from the Eurasian plain to the interior of America, and here he can only marvel at the differences. “Continental truckers in Europe had the border queues for Russia and Hungary,” lie writes. “In America you had Texas.” In Europe, truckers keep their trailers spotless; in America, Coster finds them festooned with slogans like “If You Can’t Run with the Big Dogs Stay on the Porch,” “Intellect Is Invisible to the Man Who Has None,” and “Nothing Needs Reforming So Much as Other People’s Habits,” leading him to remark brightly, “If Schopenhauer had had the chance to visit Truckworld . . . he’d have seen that the Road Kill Cafe T-shirts said it better.”

A Thousand Miles from Nowhere works at every level, but it leaves a few things unsaid. I wish, having marveled throughout my travels in the mountainous West why more big rigs don’t go plunging off the cliffside ledges that often pass for highways in these parts, that Coster had given us a bit more “thick description”—or even a heavier dose of gonzo—on the actual business of operating a truck. I would like him to have explained why truckers find it necessary to dog the tails of small cars at great rates of speed in the most inclement weather, why they eat like Elvis, why so many people are lured to a hard life of hemorrhoids and bad coffee on the road.

But I am glad to have what Coster gives us here: a good anti-romantic look at the world of trucking, a glimpse inside the cab. “Travel writers may still essay trans-navigation of the globe by antique steam-engine or renovated sail-boat, but trade doesn’t,” he remarks, and his devotion to the real world is welcome. It is also a challenge to American writers to do him one better on their own turf, and to bring the big rigs within the scope of our literature.

[A Thousand Miles from Nowhere: Trucking Two Continents, by Graham Coster (New York: North Point Press/Farrar, Straus & Giroux) 175 pp., $20.00]

Leave a Reply