It may be an embarrassing admission for somebody who has been a book review editor for the last 14 and a half years, but the truth is I had never heard of Tony Hillerman until May 1989, when I began traveling in the Southwest in connection with a book-writing project I am working on and the wife of a friend of mine in Ignacio, New Mexico, asked casually if I had read any of Hillerman’s books. These she described as detective novels set on and around the Navajo Indian Reservation, and since I had already spent time wandering on “the Res” (as it is known locally) and planned to spend more time, I kept an eye open for Hillerman’s work and bought a couple of paperback volumes when I came across them. In the subsequent 14 months I have read eight of his eleven novels for adults (a twelfth is for children) and am on the lookout for the other three. He has several more under contract, and when Harper & Row publishes them I am going to read those, too. This makes Tony Hillerman the third detective novelist, after Conan Doyle and Raymond Chandler, whom I have any interest in reading at all.

Yet Hillerman is no Chandler. “Intellectuals” (“innerieckshuls,” Flannery O’Connor called them) love Chandler, but I doubt if they number very many of Hillerman’s fans, though I may be mistaken in that. Tony Hillerman is not, even in the best sense of the term, a literary novelist. He is neither a poet nor a stylist. He is not a novelist of ideas, or of attitudes. He lacks that quality of “magic” that Chandler (quite modestly) recognized in his own work, as well as the “charm” Chandler found in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s (“a kind of subdued magic, controlled and exquisite, the sort of thing you get from good string quartettes”). He exhibits, typically, a tin ear for human speech, and those of his characters (in particular his two mutually offsetting protagonists. Tribal Police Officer Jim Chee and Lieutenant Joe Leaphorn) who reappear from one book to the next do not really develop as human beings at all. His “plots” are not always satisfactory, being grounded often in unconvincing human motives—although they are nearly always better resolved than Raymond Chandler’s. But: Hillerman is a compelling storyteller, skilled in the oldest and most fundamental of the arts, and as a storyteller he has the most basic kind of integrity. There is nothing either cheap or dishonest—ever—in Tony Hillerman’s work. He never (deliberately) fudges, and he does not pander at all; and while he has been accused of portraying Navajo culture and contemporary life in somewhat idealized terms, “the Res” is the indispensable omnipresent grounding of all his fiction as much as Southern California is of Chandler’s, though not with the same poetic intensity.

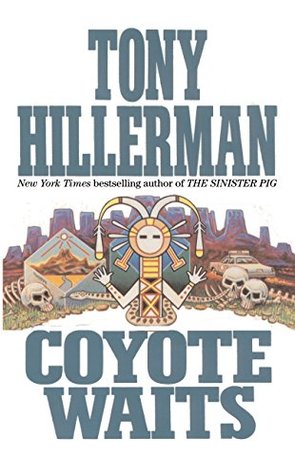

Actually, Coyote Waits shows marked literary advancement in many respects over its predecessors (although my favorite Hillerman book to date is still People of Darkness, a clever, inventive, and lovely novel), a sign that its author is finding out his own weaknesses and working upon them. The dialogue, for one thing, is much more easy and natural in Coyote than in the earlier books, Hillerman having—almost—divested himself of irritating linguistic ticks. (Hillerman characters are inordinately fond of concluding their sentences with the phrase, recognizable by all Hillerman readers, “that sort of thing.”) Coyote Waits, in fact, comes much closer to qualifying as a “literary novel”—I know, I know: supply your own definition—than anything he has previously written. Hillerman still needs to move his characters off their identifying stases (Leaphorn’s love for his dead wife, Chee’s love for the Navajo lawyer Janet Pete that is apparently as eternal and unavailing as if Pete and Chee were figures on a Grecian urn, the white trader McGinnis’ patient alcoholism, and so on). But Hillerman may be learning now as fast as he writes, and he writes very fast. In addition to the 12 fiction tides are five nonfiction books to his credit, and Hillerman—a former newspaper editor—did not begin writing books full-time until he was into his 40’s.

The action of Coyote Waits occurs, as it does in many of Hillerman’s books, in the fall—apparently a season as special to Tony Hillerman as twilight was a special time for William Faulkner. It is a good season for the setting of a Western novel, and a Southwestern novel in particular. It is a season always of waiting, of anticipation, of sharpness in the air, and of mystery. And that is all that I am going to tell you now about the story Coyote Waits.

[Coyote Waits, by Tony Hillerman (New York: Harper & Row) 304 pp., $19.95]

Leave a Reply