Ever since the cinéaste Nino Frank first used the term in France in 1946 (he never said he invented it), there has been considerable controversy about the meaning of “film noir” and various attempts to define it, some more or less authoritative. The essential arguments have been usefully collected in Silver and Ursini’s Film Noir Reader (1996).

Because of the collaborative nature of film, there have been varied emphases: graphic, obviously; sociological and political, having to do with World War II, the return of the GIs, crime and corruption, and even the McCarthy episode; literary definitions, acknowledging such writers as Hemingway, Hammett, Chandler, McCoy, Woolrich, Goodis, and so on; even an immigrationist perspective, having to do with German and other artists who brought certain stylistic preoccupations with them. These arguments are concerned with the period of 1941-58—or 1939-59, as has been argued—and leave open subsequent developments such as “neo-noir” in the 70’s, 80’s, and 90’s. Are these last (such as Chinatown, Farewell, My Lovely, Reservoir Dogs, The Usual Suspects, and Twilight) homages, pastiches, recreations, or what? If noir is a cycle confined to an identifiable period, how can there be “neo-noir“?

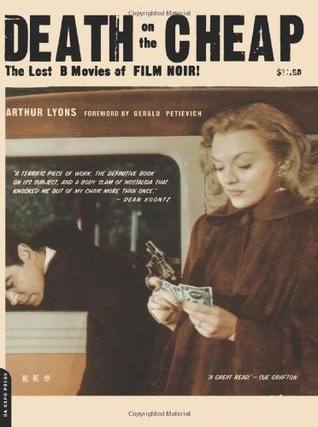

Arthur Lyons, in his interesting and flawed little book Death on the Cheap: The Lost B Movie of Film Noir, has provocatively questioned the standing definitions of film noir. Lyons has dismissed the usual guff, displaying contempt for the usual language of film criticism, and he can’t be faulted for that. Too much of the language of film criticism is opaque or off-putting or pretentious, phony, and wrong. There comes a point when cultic academicism goes too far. Lyons shows that there also comes a point when it doesn’t go far enough.

The best part of his book is his dismissal of previous definitions. He apparently thinks that noirs are just juiced-up B movies. Lyons emphasizes economics in the definition of noir and neo-noir, suggesting that such films have more to do with escape, entertainment, and vicarious thrills than with a national mental dysfunction. And he goes further, quoting Gerald Petievich: “Story and story only defines film noir. Director tastes and techniques have nothing to do with the archetype noir tale.” Lyons, insisting on thematics—alienation, social corruption, obsession, fatalism, and sexual perversity—sees film noir as nothing more than a faddish way of packaging the crime film. “Film noir” is for him a back-projection by intellectuals: He suggests that nobody who made film noirs in the first cycle knew they were making them, though the very phenomenon suggests that the opposite is true. Quoting clueless actors doesn’t prove anything.

But Lyons does not sustain his argument about “story.” He invests only 66 pages of exposition in the literary background and the history and economics of the B film before devoting nearly a hundred pages to a “filmography”—an alphabetized list of forgotten flicks that his subtitle implies are essential to film noir. This filmography (and its glossy photos) will, no doubt, sell his book; but it is not vitally related to his argument, and it even contradicts it. Having insisted on “story,” he refers again and again to style, noted cinematographers, and connections to other film noirs, implying an acknowledgment of style. Furthermore, many (if not most) of the films he glosses are negligible, or just plain bad—causing him to veer into vulgarity and fanzine-type irrelevancies, reciting the campy stuff about Sonny Tufts (a favorite sneer-target of Johnny Carson), and telling us who Von Stroheim was shacking up with when he made The Mask of Diijon (1946), and how Liz Renay, who played a gangster’s moll (Date with Death, 1959) really was one (Mickey Cohen’s), and how Tom Conway died destitute, and how Barbara Payton (Bad Blonde, 1953) was arrested for prostitution, drunkenness, and writing bad checks, but was not arrested for writing her autobiography, I Am Not Ashamed. None of this stuff matters as far as the viewing experience goes, and even there it is rather deflating to read, as in his discussion of Key Witness (1947): “Dumbly overwritten and only marginally acted, this forgettable programmer has appropriately pretty much been forgotten.” If that is so—and I don’t doubt that it is —then life is too short not only for viewing that movie, but also for reading about it.

Nevertheless, Death on the Cheap is good to have for its exposition regarding B movies and the citations of some good noirs that many people today are in search of. Lyons has succeeded in his way, but the perplexities of noir theory and the questions he raises about the quality of the films are hardly resolved.

[Death on the Cheap: The Lost B Movies of Film Noir, by Arthur Lyons (Cambridge: Da Capo Press) 212 pp., $17.50]

Leave a Reply