“Who reads?” That’s what I’ve heard more than once from an “English professor” who spends a lot of time online. Well uhuh, I say, sounding rather like Butt-head, I uh, um you know, read stuff, but he listens not to me. And I admit that I read less than I used to. On the other hand, I think I read 30 books last month, and I wasn’t even trying. And most of them were “out of my field,” whatever that is. So yes, there are those of us who still read books, though that may have to be classified information as far as the academy is concerned.

One problem with reading is that it may conflict with musical and cinematic needs as well as life itself, but still we can relate even such experience to reading. So this is where I must acknowledge that I came into my experience with David Goodis backward or anachronistically or mediated by the media—that is to say that my acquaintance with him was based on films made from his work. And that was a justifiable pleasure. I always liked Delmer Daves’ Dark Passage (1947), so much so that I think rather heretically that it is the best of Bogart and Bacall’s joint appearances. But even so, I was most impressed, even surprised, by the strength of the original work, a powerful source for the film. The ending is much better than the sentimental conclusion of the film, and the limited third-person narrative is so circumscribed that it seems like the voice-over of the movie. It is a compelling read in a savage sense. In effect, you were mugged by a pro, and loved it. “And when you’re slapped you’ll take it and like it.” Now who said that to whom in what novel by what author? Quote No. 2: “Shut your mouth, dame, / Or with this paper shall I stopple it.” Who to whom, with title, act, scene, and lines—and make it snappy: There’s a lot at stake as we identify the sources of noir. Hint: In 1948, Laurence Olivier and Orson Welles agreed that Shakespeare was noir.

Nightfall (Tourneur, 1957) is another admirable film, not flawless, but treasurable. And again Goodis has no problem excelling the film. His hypnotic projections are in themselves practically a drug problem. Maybe he or his work should be trucked across the border from Mexico, in order to satiate—though only temporarily—my lurid desires. Help! I’m stuck in an old paperback and loving it!

Then there is The Burglar. Paul Wendkos’s 1955 movie was held up until 1957 and then released in order to exploit the fame that year of Jayne Mansfield. The movie is remarkable for being photographed on site in Philadelphia, for the outrageous Wellesian cinematography and editing, for the gloomy contribution of the iconic Dan Duryea, and for being the only evidence I know of that Miss Mansfield, in nongrotesque mode, could actually act. Need I add that the novel is even better, a tragic exposition that is artfully constructed? Compare p. 415 with p. 443 of this edition, and note the dovetailed imagery. Yes, Goodis is good. The Burglar maxed me out in sheer Goodisness, but then The Moon in the Gutter has one of those titles that encapsulates Goodisism, and there again the French noticed. And Street of No Return is so bleakly down and out that the spirit of Samuel Beckett looms out of the miasmal mist of hopelessness.

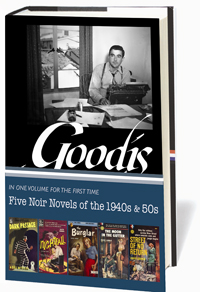

We knew this was coming, did we not, when the Library of America included Down There by David Goodis in the second volume of American Noir 15 years ago—the book that was the basis of Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player (1960). Yes, David Goodis wrote a lot of compelling stuff, so the recognition is warranted, and probably Cornell Woolrich will join him one day, wrapped with all the dignity accorded a corpse at an upscale funeral. That black dust jacket becomes David Goodis (1917-67) like a tuxedo in a coffin: He has become the corpus of his work. And that is appropriate, because he was an obsessive writer, if ever there was one. So this is the moment to reflect on the arc of Goodis’s career, on the qualities of his best work, and even to predict the future of his reputation, as it proceeds from this height. He had been on certain heights before, writing about the lower depths.

David Goodis was a Philadelphia kid, a good student who majored in journalism at Temple University, but who then became a pulp writer, putting journalism away. He was descended on both sides from Russian Jewish immigrants, and had no difficulty not only in assimilating America, but even in forging a powerful vision of America. And he wasted no time in doing so. He got to work producing novels and stories, soon claiming that he had in the early 1940’s turned out over five million words in five years, writing under several pseudonyms for as many as 20 pulp magazines and even turning out 10,000 words per day. Now try that sometime on an old typewriter! Such a production would seem to be damaging and destructive, but it was not then yet so for him, if ever it was.

During this period, Goodis was married and divorced, and Hollywood beckoned. The big time was calling—Dark Passage was serialized in The Saturday Evening Post. The struggling hack had money and a platform. And then he began to lose the latter, if not the former. By 1950 he was back in Philadelphia living with his parents and a schizophrenic brother, and writing paperback originals. Later, David Goodis died not long after being mugged, possibly as a result of that violence. His work went out of print, was revived in France, and then here. The story seems familiar, with overtones of Brockden Brown, Poe, Lovecraft perhaps, and Woolrich as well.

Goodis excels in intensity, focus, and rhythm. His best work drives toward a fusion of consciousness, melding or melting narrative into realization, or story into awareness. His most characteristic moments are those of unvoiced dialogues—conversations that are imagined by the protagonist, but are no less real for that. Needless to say, his work must be experienced to be appreciated. Now is the time, and this volume is the opportunity, before Goodis gets the treatment as the ethnic writer he wasn’t, and also as a homosexual precisely because there is no evidence of that disposition in his work. I see him as a prose-poet melodramatist of gnostic bent, one whose quality trumps any quantitative considerations. Such a performer makes us feel that we owe something to him—and our rapt attention is what he wanted and still rewards. Or put it another way: In America, dreams become nightmares—yet some few of these grotesque visions are exquisitely rendered.

[Goodis: Five Noir Novels of the 1940s & 50s, edited by Robert Polito (New York: The Library of America) 808 pp., $35.00]

Leave a Reply