Like all relationships, the special transatlantic one is in a state of constant flux—warmer or cooler at different times, enhanced by empathy, marred by misunderstandings, riven by reality—but always affected by the personal qualities of the incumbents of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue and 10 Downing Street.

For a short but eventful span between January 1961 and October 1963, the United States and Britain were presided over by an apparently comically mismatched duo: John F. Kennedy and Harold Macmillan. It is Christopher Sandford’s design to explain why this double act worked better than might have been expected—mending fences post-Suez, facing down Khrushchev over Berlin and especially Cuba, trying to reduce the number of nuclear weapons, and tamping down postcolonial bushfires from Congo and Laos to British Guiana. In so doing, he hopes to burnish “Supermac’s” reputation and explain a few of his failures.

Sandford has written extensively on both the politics and culture of the 60’s, including a series of books on the Rolling Stones. This breadth of references stands him in good stead for analyzing Kennedy, who was himself rather like a rock star—idolized, married to a celebrated beauty, and, as a forty something non-WASP Democrat, potently symbolic not only of a burgeoning superpower but of a whole new kind of country. The contrasting Conservative prime minister was in his 60’s and sometimes looked older, his public persona shabby-genteel and understated, out-of-date even by British standards, lampooned by satirists, underestimated even by allies, a kind of avatar of the old Europe that had so recently needed to be rescued by American manpower and materiel.

“Jack” alternated between Mad Men-like elegance in D.C. and preppy ease in Hyannis, while the other shuffled around Westminster in scurfy suits, and at home in Sussex in egg-stained cardigan and broken-down slippers. One officiated in an atmosphere of cool Roi Soleil expansiveness (his First Lady’s good taste in interior design is still detectable in the White House), while the other read his red boxes between paint pots and ladders during a begrudging and interminable revamp of always cramped quarters. One was priapic to an extreme degree, seducing bevies of beauties, including (probably) Marilyn Monroe, while the other usually went to bed with Jane Austen. Moreover, Macmillan had disliked Kennedy’s father (who had been U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom between 1938 and 1940) and had a generally low opinion of American politicians, up to and including Kennedy’s deputy, Lyndon Johnson. As the author notes dryly, “the personal omens for the relationship could scarcely have been less promising.”

To add to the imbalance, Britain was effectively a client state in the wake of Suez, a bruised ex-behemoth begrudgingly passing the global baton to brasher cousins; as Dean Acheson famously observed in 1962, she had lost an empire but not found a role. The historically minded Macmillan once described the British-American relationship as akin to that which had subsisted between classical Greece and Rome.

Yet Macmillan’s at-times-patronizing view of the United States was counterbalanced by genuine admiration. However much he may have resembled a Central Casting English milord, he was in fact solidly bourgeois, with a family fortune derived from the eponymous publishing firm. Furthermore, his beloved mother had been born and reared in Indiana—which gave him some insight into American life and attitudes. As Sandford observes, “[S]uperficially the English gentlemen, Macmillan remained immensely proud throughout his life of the ‘New World spirit of enterprise’ represented by his mother.”

Sandford also cites an un-Conservative aside made by Macmillan to a Labour minister: “Europe is finished. It is sinking. It is like Greece after the second Peloponnesian war . . . If I were a younger man, I should emigrate to the United States.”

Although Macmillan represented the poor relation in the transatlantic alliance, he also resembled an indulgent father, looking on in envy and wonder at this freer generation, yet quietly certain of having insight and experience for which he expected acknowledgement (which sometimes he received). The author notes, “It would be possible to speculate that Macmillan saw in John Kennedy the disciplined, self-confident son he never had.”

Underestimations to the contrary, Macmillan was wily and steely, well informed and longsighted. A shrewd State Department briefing informed Kennedy that the apparently scatty denizen of Downing Street was in fact “tenacious and self-reliant . . . he is a deft and astute politician [and] exercises a decisive voice in all major areas of policy.”

Macmillan was also more a man of his time than he pretended to be. Affectations like referring to hamburgers as “meat sandwiches” masked a fundamental realism; he understood the way the world was moving, although he did not like it much. His fusty persona was deeply reassuring to conservative-minded Britons, but it was also misleading. Like all postwar Conservative leaders, Macmillan was either unable or unwilling actually to conserve anything. As Sandford remarks, “no-one could have sugared the pill of Britain’s continuing global decline better.”

Perhaps more surprisingly, Macmillan was more of an idealist than his counterpart, much given to abstractions and motivated by a passionate wish to rid the world of as many nuclear weapons as possible. He was keen on Keynes and modernization, and detested by the Tory old guard for presiding over the winding up of empire (as if he had much choice in the latter). Kennedy, on the other hand, was a realist rather than a visionary, whose interest in civil rights and other fashionable causes was often tepid, a question of political calculus rather than moral principle. His anticommunism was sincere—he was the only sitting Democrat who did not vote to censure Joseph McCarthy in 1954, although this was also a matter of family loyalty, as his father had been a supporter of McCarthy and his brother, Robert, had worked for him. His anticommunism could lead him into brinkmanship, and it was the superannuated and supposedly stodgy Conservative who was always the more likely to advocate consultation instead of hazardous confrontation with the Soviets. It is perhaps germane to recall that Macmillan had been a senior member of the government which after 1945 had readily handed over anticommunist Russians to the Soviets in the full knowledge that many of them would be murdered. One could not imagine Kennedy being party to any such dishonorable action. But Macmillan’s feline humor sometimes helped defuse Cold War tensions, such as the time he came out of a meeting with the Russians, commenting that “the Soviets may know how to make Sputniks, but they certainly don’t know how to make trousers.”

There were yet other factors oiling the alliance: Both leaders were war heroes, both were well read, both were impatient of pettifogging, and both were criticized for having patrician airs in an age increasingly uncomfortable with any manifestation of authority. Macmillan was also fortunate in his ambassador to the United States, David Ormsby-Gore, who was very close to Kennedy, and in his foreign secretary, Alec Douglas-Home, whom Kennedy liked greatly. Macmillan also got on very well with Jackie, to the extent that he and she would correspond for over 20 years after Kennedy was shot.

Macmillan was often supplicatory in his correspondence and occasionally pettish, while Kennedy was always cooler and more enigmatic. But for that short international interlude before the one was killed and the other invalided out, Washington and London worked together more comfortably than at most times since 1815, and did some good in the world. The alliance has never been so close since, not even in the Thatcher-Reagan period, since which it has become increasingly uneven. (Sandford is plainly disgusted by Tony Blair’s sycophancy.)

The long-term prospects for the Special Relationship are not especially promising, as, whether led by Democratic, Republican, Labour, or Conservative politicians, both countries seem eager to erase their unifying English inheritance. The United States sometimes seems to be racing the United Kingdom to the geopolitical bottom, and mainstream Americans may soon comprehend with what sorrow and defiance ex-imperial England dealt with its diminished destiny. Macmillan (then chancellor of the exchequer) said to John Foster Dulles shortly after Suez that “the British action was the last gasp of a declining power and that perhaps in 200 years the United States ‘would know how we felt.’”

His 200 years may be nearer to 100, but be that as it may it is salutary to look back at times when, whatever their flaws as men, idealists without illusions led two of the globe’s great powers.

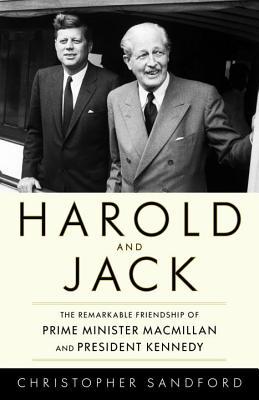

[Harold and Jack: The Remarkable Friendship of Prime Minister Macmillan and President Kennedy, by Christopher Sandford (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books) 313 pp., $25.95]

Leave a Reply